San Diegan’s enthusiasm for life and thirst for knowledge inside and outside of sports was contagious

Thank you, Bill Walton.

You got me started.

“Write about something that interests you,” said one of my junior high school teachers, soliciting articles for the school newspaper.

Blowing a great chance to interview girls in my class, I chose to write up Walton’s Portland Trail Blazers, correctly forecasting them as 1977 NBA champions.

Never mind that my school was in Dayton, Ohio.

Walton, the bearded, 6-foot-11 redhead, transcended zip codes.

He’d won 88 consecutive games with UCLA, following similar basketball artistry with Helix High School in San Diego.

Giving a transplanted Southern Californian a closer look at him, the Dayton Flyers tested Walton’s final UCLA team as few could. Not until the third overtime did Walton seal the win in Tucson, Ariz., launching his final bid for a national title that came up short opposite David Thompson and N.C. State.

Later, when Dayton’s Johnny Davis joined Walton in Portland, I became a Walton fan.

I liked how he got his teammates involved. Most centers lacked that skill.

Walton sparked my interest in not only the ’77 Blazers but also many of his other pursuits.

He was a great ambassador for San Diego, for basketball at large, for the 1986 Boston Celtics with whom he was the NBA’s Sixth man of the Year, for all things UCLA and the Pac-12 Conference, for the city of Portland and the state of Oregon.

He brought intrigue to the Grateful Dead experience. He went on about his soon-to-depart San Diego Chargers, green energy’s potential, solving San Diego’s homeless crisis and the need for more substance-abuse programs.

He waxed on about artists, musicians and the six Hall of Fame coaches who guided him.

He raved about the life-enhancing work of a San Diego surgical device manufacturer and a spine surgeon who’d chased away his thoughts of suicide following a hellish two-plus years of pain and immobility.

Getting him to talk about his formative years, though, wasn’t easily done.

In my few interviews with him as a newspaper reporter, Walton preferred to riff on other topics rather than revisit his UCLA career at length or to talk about himself a whole lot.

Fortunately, a lot of ground was covered by author David Halberstam in his terrific 1981 book “The Breaks of the Game” and by sportswriter Curry Kirkpatrick in Sports Illustrated during Walton’s college days.

It’s stunning, in retrospect, to contemplate what Walton would’ve commanded financially in today’s name, image and likeness market while leading UCLA to a pair of national titles and a semifinals game.

It’s almost surreal to ponder his college activities away from the basketball court.

Taking a stand, being a student of life, shaped his UCLA experience at a time when many students were protesting the Vietnam War.

The approach, Kirkpatrick wrote during Walton’s junior year, would lead UCLA’s star center “to lie down in the middle of Wilshire Boulevard in a peace protest, to march through classrooms, to barricade doors with wooden horses, to ride a janitor’s scooter up the hill by the administration building and to decry loud and long the government’s mining of Haiphong Harbor.”

The young San Diegan wasn’t done there.

“Walton refers to himself with disdain as ‘The Great White Hope,’ ’’ Kirkpatrick wrote.

Halberstam praised the guidance of Gordon Nash, the coach at Helix, and Walton’s parents, Ted and Gloria, who brought their children up in La Mesa.

A biology teacher, Nash succeeded at keeping basketball fun amid all of the attention Walton drew from recruiters and media.

Ted was a social worker, Gloria was a librarian.

Ted’s anger, Bill Walton remembered, seemed reserved for those who were contemptuous of the poor.

The parents had heard many stories about college recruiters showering basketball players with gifts.

“They decided most vehemently they would not let this happen to their children” who included football standout Bruce Walton, who would play for UCLA and the Dallas Cowboys, wrote Halberstam.

It was in San Diego also that Bill developed his basketball foundation as a pass-first offensive player.

Because he was too advanced for players his age, Walton competed at guard against older, bigger players while he was in grade school.

In contrast to most big men in college and the NBA, he developed a guard’s view of the entire court, and he could, as few centers could, see an entire series of moves before they developed, Halberstam wrote.

“He was growing up in the game he loved, depending not on his size, which was to be quite special, but on his vision and quickness,” the author wrote. “He learned, and learned well, that basketball was not a game of height but a game of quickness, of using speed to set up an intricate series of moves so that one player would end up with a one-step advantage on his opponent.”

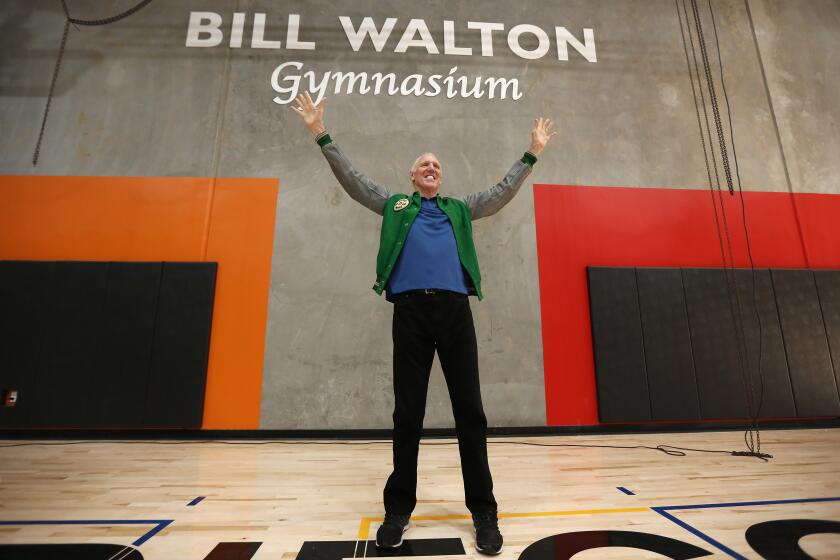

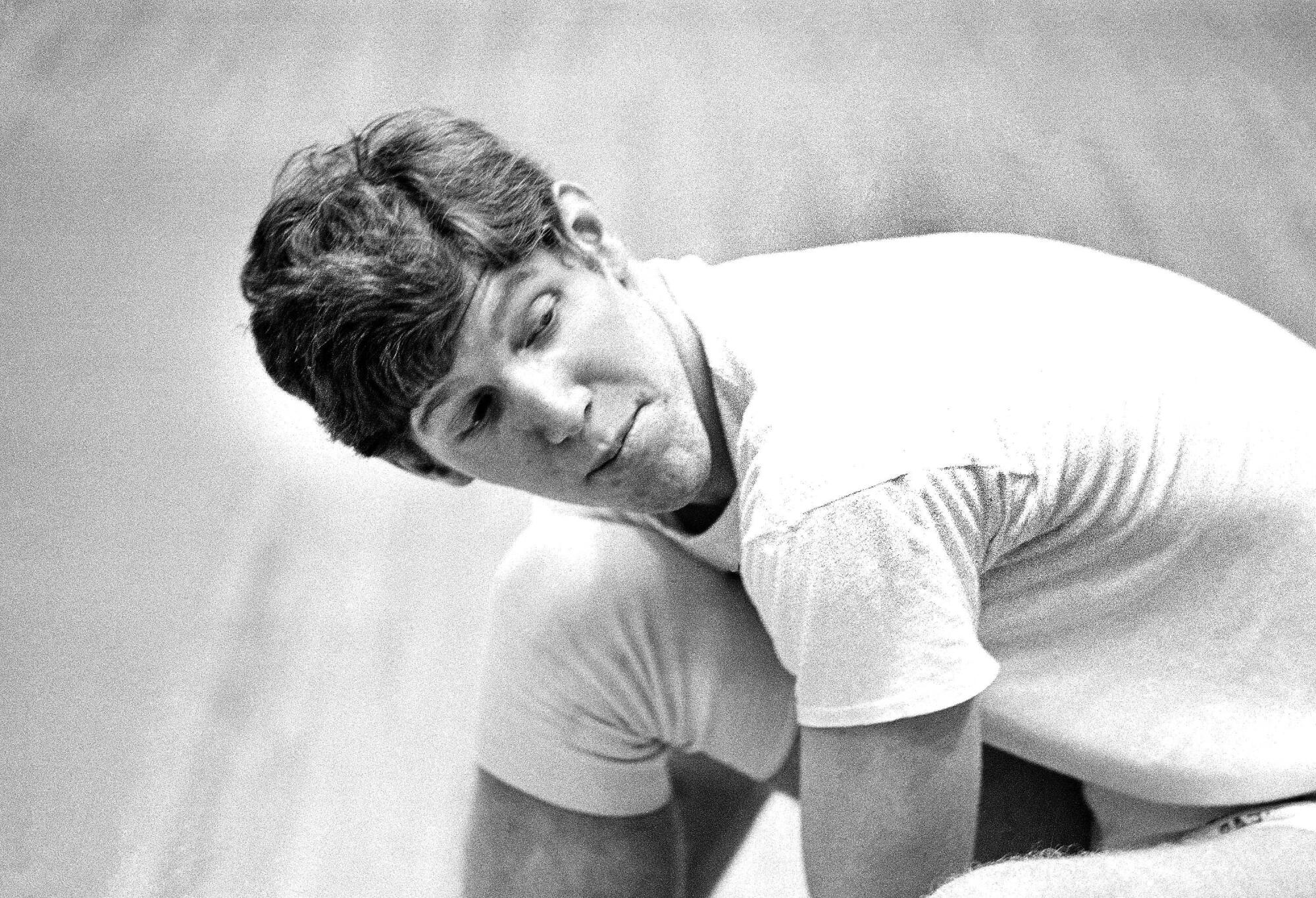

Bill Walton starred at Helix High School and UCLA before his long, accomplished NBA playing and broadcasting career. San Diego was always home.

Nash speculated that Walton liked to pass because he already got more attention than he would’ve wanted, for being so tall and so capable at other facets of basketball.

Going into his senior year, the 6-foot-9, 170-pound Walton begged Nash to allow him to focus on defense and rebounding.

“It was not, Nash thought, that Walton lacked ego (his ego, the coach suspected, was immense, no one could compete at that level of athletics without a big ego),” wrote Halberstam. “It was that he was more in control of his ego and knew how to funnel it into the game itself, the better to help his teammates and in the process the better to exhibit his own unusual talents. He understood very early that shooting and scoring points did not separate him from the crowd or make him a world-class player, but taking his speed and intelligence and using to heighten the skills of his teammates did.”

Even though injuries slowed him down in the NBA, sidelining him for the equivalent of nine NBA seasons, Walton impressed NBA experts with his versatility. He wasn’t clunky. Coach Red Holzman of the Knicks once said if Walton were smaller, he could’ve become an NBA guard.

For all his successes on the court and as a basketball broadcaster whose riffs went viral on social media, Walton was often remembered this week, following his death from cancer, at 71, for his zest for life.

My favorite Walton tribute came from Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who preceded him to UCLA and the NBA.

“On the court, Bill was a fierce player,” Abdul-Jabbar wrote. “But off the court, he wasn’t happy unless he could make everyone around him happy.

“He was the best of us.”

Go deeper inside the Padres

Get our free Padres Daily newsletter, free to your inbox every day of the season.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.