The race for Mars is on. NASA hopes to land the first Martian in the next decade, and the agency’s not alone: The China National Space Administration, Indian Space Research Organization, and Russia’s Roscosmos, as well as Elon Musk’s SpaceX have similar aspirations.

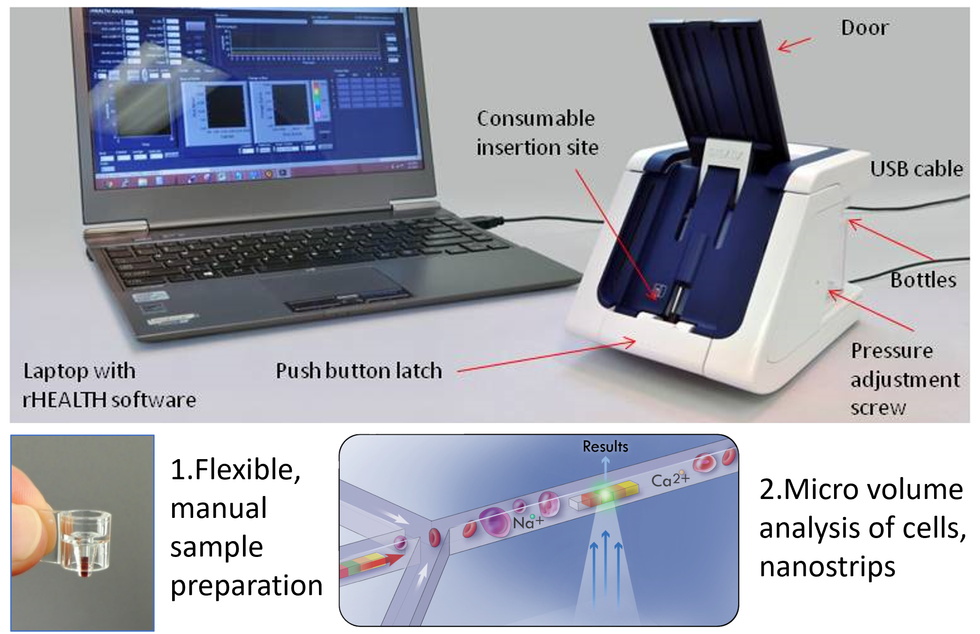

Yet the trip to Mars a long journey, filled with questions about how interplanetary trips affect human health. A paper published in Nature Communications puts the spotlight on a device that is helping to find answers: the rHealth One, a single-drop flow cytometer. The rHealth One was sent to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2022 to test its capabilities in orbit, and the results from that experiment have implications for health on Earth as well as Mars.

“The rHealth One exceeded expectations,” says Eugene Chan, CEO of rHealth. “[We’re] putting it on a rocket that goes up to nine Gs during launch, and when it gets up there, it’s in zero gravity... the fact that everything worked out perfectly kind of blows my mind.”

Re-thinking the Cytometer for Life in Space

Flow cytometers are an important diagnostic instrument that blasts cells with laser light and identifies different types of cells based on how light scatters. They were popularized in the 1970s as an alternative to viewing cells through a microscope.

“If you’re looking at cells in your blood in a microscope, you see red blood cells... but if you are after the more interesting type of cells, the white blood cells and their subtypes, you’re almost missing them because you’re overwhelmed by all the other cells. The flow cytometer really revolutionized that problem,” says Edwin van der Pol, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and physics at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

But conventional flow cytometers have a downside: They’re large and heavy. Most are desktop devices that weigh between 20 and 120 kilograms. That’s not a major issue in a medical facility but when it comes to launching a device into space, every kilogram counts.

“The fact that everything worked out perfectly kind of blows my mind.” —Eugene Chan, rHealth

“What we’ve been able to do is shrink this thing down a hundredfold in terms of mass, volume, and power, so that the entire cytometer is the size of a matchbox, and that fits inside the [rHealth One],” says Chan. The rHealth One weighs 1.5 kilograms and measures roughly 18 centimeters long, and 13 centimeters deep and tall.

To shrink the cytometer, rHealth One rethought the engineering of a flow cytometer with a focus on miniaturization. The printed circuit boards are cut down and integrated, the optical module is simplified, and the laser is reduced in size and output.

“If you compare the rHealth One to any flow cytometer that you can now commercially buy, it’s a big revolution,” says van der Pol. That’s not to say the rHealth One is a replacement for its predecessors: Rather, focusing on miniaturization and durability makes it possible to re-think assumptions of how a cytometer should be engineered.

The optical system is a key example. Most cytometers have optical systems that provide adjustments for future correction and calibration, while the rHealth One uses epoxy to fasten and seal the “optical block,” which reduces complexity, increases durability, and prevents unwanted movement when used in a zero-gravity environment.

Bringing the Cytometer Home

Once aboard the International Space Station, the rHealth One was tasked with measuring three types of prepared samples that contained a variety of particles designed to test the cytometer’s accuracy. Each sample was observed on Earth, then again on the ISS. The rHealth One’s results were largely on-target, with one exception: a single sample returned unexpected readings.

“The NASA guys said, hey, that doesn’t look like what the sample is supposed to be,” said Chan. “Maybe the astronaut carrying it it put in some corner of the spacecraft that is a little colder, or warmer, or whatever.” The sample was sent to Johnson Space Center for further analysis, which found the rHealth One’s unexpected measurements were accurate. Something—what, exactly, is unknown—had altered the sample in transit.

That underscores why a cytometer can prove useful in space. A long journey through space is likely to have unexpected impacts on the astronauts making the trip, as well as other living organisms sent on the journey. A cytometer gives astronauts en-route (or on) Mars a tool to analyze cells and observe changes that might otherwise go unnoticed.

And it holds potential on our home planet, as well. “In a home-based setting you can take more measurements, you can capture more points in time, to make sure you’re catching events and don’t miss anything,” said Eugene.

The rHealth One’s design already hints at this direction. Aboard the ISS, the device’s power and data were provided over a USB cable to a laptop running rHealth’s software. Sample runs averaged more than 71 million raw data points and were streamed in real-time, with reach run completing in roughly two minutes.

Chan said people undergoing cancer treatment are one group who could benefit. Cancer treatment typically includes frequent blood counts which currently must happen in a medical setting. Bringing a cytometer into the home would allow more frequent and convenient testing. That could also prove useful for people with other conditions that require frequent testing, such as blood cell disorders.

A future version of the device, the rHealth Awesome, will look to further refine the design and software for ease of use. “Essentially, you can get all the diagnostics that you would using the rHealth One through a fairly dumbed-down app. That’s where we are right now, and I think we’re close to achieving victory on that as well,” said Chan.

- Astronaut Bioengineers Human Cartilage in Space Using Magnetic Fields ›

- Moondust, Radiation, and Low Gravity: The Health Risks of Living on the Moon ›

Matthew S. Smith is a freelance consumer-tech journalist. An avid gamer, he is a former staff editor at Digital Trends and is particularly fond of wearables, e-bikes, all things smartphone, and CES, which he has attended every year since 2009.