Structural Considerations: Infill and Material

The structural design of the wind turbine blades was based on both the study of different infill structures and 3D printing material.

1. Gyroid Infill

Components such as wind turbine blades often experience a constantly changing load because of aerodynamic and inertial forces during rotation. After extensive infill research, gyroid’s isotropic properties made them an obvious choice as they endure loads that constantly fluctuate.

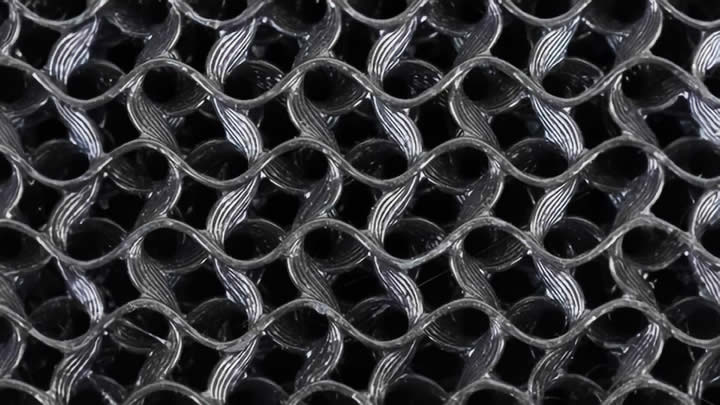

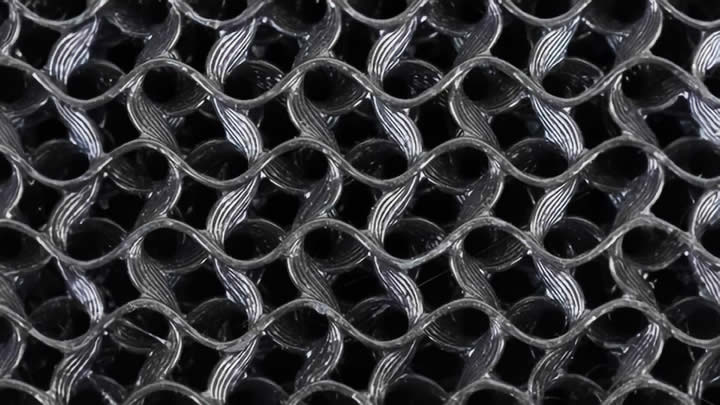

The gyroid infill is made of a complex network of twisted and interconnected tubes forming a repeating pattern that extends infinitely in all directions without intersecting or overlapping. The result is a continuous lattice structure resulting in extraordinary stability at very low density which were the mainstays necessary for lightweight rotor blades. While designing this complex pattern manually might take ages, 3D printing software simplified the process automatically and implemented it in the rotor blades.

The rotor blade’s gyroid infill printed by the BigRep ONE at the maker space of TH Wildau.

Apart from its strength, gyroid infill is also known for its material efficiency. Because of the interconnected channels, it reduces material usage without compromising structural integrity. This aspect was a huge advantage while printing the blades which might have otherwise ended up being heavy and consumed a substantial amount of material.

2. BigRep’s Industrial Grade PRO HT

The research team printed the rotor blades with BigRep's PRO HT filament as it checked the boxes: easy to print, high strength, and has the ability to withstand high temperatures. The user-friendly filament doesn’t warp often and delivered aesthetic prints with a smooth matte finish.

The team also considered the ecological footprint of the blades, and the industrial grade PRO HT being a biopolymer, has a reduced environmental impact when compared to filaments derived from fossil fuels.

Putting the Blades to the Test

Testing the 3D-printed blades involved structural and wind tunnel tests to evaluate how they hold up under a range of parameters.

1. Structural Testing

The prototype rotor blades were exposed to the ULCs (Ultimate Load Cases) with the Universal Testing Machine (UTM) at HTW Berlin.

Ultimate Load Cases (ULCs) encompass extreme loads applied during testing, while a Universal Testing Machine (UTM) is the device used to simulate or apply ULCs in structural testing. The machine evaluates how materials behave under controlled forces or strains.

What are Ultimate Load Cases (ULCs)?

The conditions under which a material or structure experiences the maximum anticipated load, stress, or forces it might encounter in the real world. By subjecting materials to these ULCs, you can gather data on how they behave under stressors which helps in the design and validation of the rotor blades for safety and reliability.

What is a Universal Testing Machine?

A Universal Testing Machine (UTM) is a device used to test the mechanical properties of materials or parts, such as tensile strength, compression, bending, and hardness. It applies controlled forces to the subject to measure how it responds under different conditions, providing valuable data for material analysis and quality assurance.

The stress tests analyzed potential damages within the 3D-printed shell like buckling and cracks when it was under certain forces. The ultimate root bending moments (maximum bending forces experienced at the root section of the rotor blade) were tested with point forces (concentrated forces exerted at specific areas) at three blade positions and in both bending directions. The blades were also tested under an intense centrifugal force of Fmax = 3000 N by a heavy-duty crane.

Despite the rigorous and thorough structural testing, the blade remained unscathed, reverting to its original shape, with absolutely no signs of cracks or buckling.

2. Wind Tunnel Tests

To help the researchers find insights into the rotor blade’s aerodynamic efficiency, structural stability, and whether the wind turbine could extract wind energy, the wind tunnel tests were crucial. The tests simulated and analyzed the wind turbine blades in controlled aerodynamic conditions within the large closed-loop wind tunnel at the HFI of the TU Berlin.

The wind turbine blades were designed to work best at a certain speed, but when they tested it, the researchers realized it worked better at a higher speed than what they had initially planned. Its maximum efficiency was at 5.4 times the speed of the wind, rather than the 4 times it was designed for. This was because the turbine was engineered based on natural wind flow, not the conditions inside the wind tunnel where it was tested.

The Future of Wind

The culmination of Laurin Assfalg and Jörg Alber’s research, the wind turbine with 1 meter 3D-printed rotor blades, currently resides at TU Berlin. It is the pillar of the course “Wind Turbine Measurement Techniques” and is a constant test subject for the experiments that determine what the future of harnessing wind energy might look like.

Apart from the enhanced performance of the 3D-printed blades, the study revealed other promising outcomes for the environment. The 3D-printed prototype blades produced for the Ph.D. thesis weren’t coated as part of the post-processing, so they can be easily recycled and upcycled. The research paves the way for further studies into enhancing the efficiency of wind turbines to harness clean, green, renewable wind energy.

This article was originally published on the BigRep blog

3D Printing Powers Wind Turbine Research At TU Berlin

3D Printing Powers Wind Turbine Research At TU Berlin

.png)