Why Dune’s feudal society taps into our very modern fears

The sequel’s archaic world seems like a parallel of today’s political anxieties and joins a long line of sci-fi classics with a a medieval aesthetic

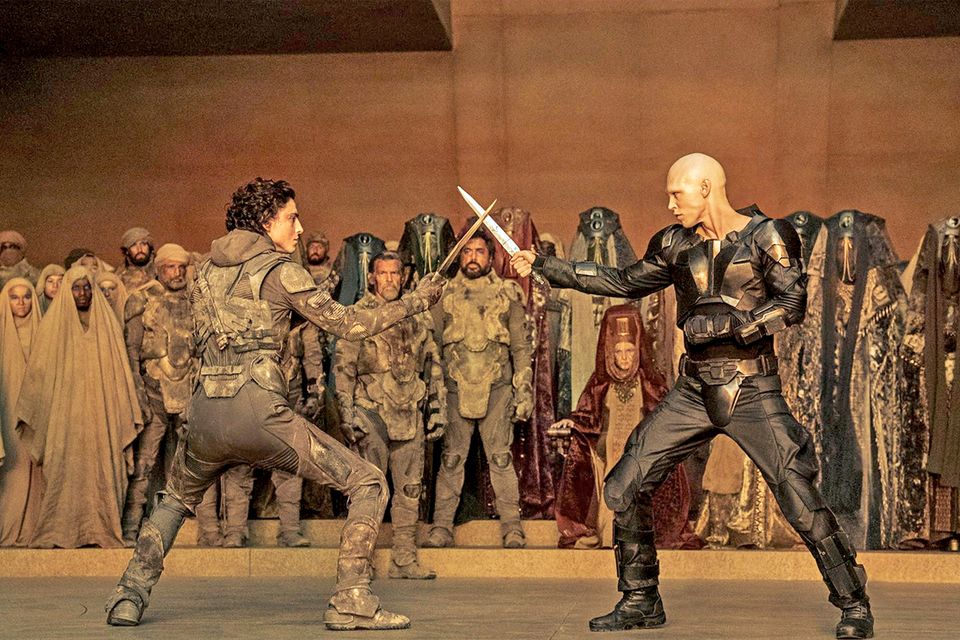

Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two arrives in cinemas this weekend. Though it’s set in a distant future filled with spaceships, lasers and forcefields, viewers might find something more old-fashioned in its feudalistic setting dominated by dukes, barons, princesses and emperors. This is a universe crafted around royal houses, gladiatorial arenas and ritualised combat. Its characters are governed by arcane tradition and whispered superstition. It’s positively medieval.

Villeneuve’s Dune duology is an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science-fiction classic, published in 1965. That novel was part of the wave of pulp fiction from the era blending a medieval aesthetic with the trappings of futurism, such as Poul Anderson’s The High Crusade and Walter M Miller Jr’s A Canticle for Leibowitz. George Lucas’ Star Wars developed from that strain of pulp science-fiction, building a galaxy of Jedi Knights, laser swords and evil emperors.

Star Wars aside, this vision of sci-fi struggled to leap from page to screen. In popular film and television, the future tended to be rooted in modernity: the utopian ideals of the Star Trek franchise, the hyper-capitalist hellscapes of the Alien or Robo-Cop series, the robotic nightmares of the Terminator or Matrix movies, or even the horrors of young adult franchises such as The Hunger Games.

There had been a minor boom in wholesome medieval epics during the 1990s, prompted by the success of Kevin Reynolds’ Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. This begat a host of similar projects, including Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, Jerry Zucker’s First Knight and even Rob Cohen’s Dragonheart. However, the genre’s popularity dwindled at the turn of the millennium.

There were a number of high-profile and embarrassing flops, like John McTiernan’s The 13th Warrior and Kevin Reynolds’ Tristan + Isolde. More broadly, historical epics struggled to connect with audiences, with notable failures like Oliver Stone’s Alexander, Alex Proyas’s Gods of Egypt and Timur Bekmambetov’s remake of Ben-Hur.

Read more

Villeneuve’s films, though, belong to a more modern wave of large-scale films and shows embracing a feudalist aesthetic. Some of these projects are rooted in science-fiction, such as Aleksei German’s Russian epic Hard to be a God or Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s goofy throwback Jupiter Ascending. George Miller’s recent revival of the Mad Max franchise, Fury Road, leaned hard into its medieval iconography, to the point that co-lead Furiosa’s (Charlize Theron) title was “Imperator”.

Outside of science-fiction, the past few years have seen an explosion of old-fashioned medieval fantasy. While Hollywood studios struggled with the genre during the 1980s, leading to infamous bombs such as Matthew Robbins’ Dragonslayer and Ridley Scott’s Legend, the success of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy paved the way for a host of imitators. The most successful of these was Game of Thrones, which spawned its own cycle of medieval fantasy shows and films.

In recent years, Hollywood has been looking for “the next Game of Thrones.” Amazon invested heavily in Wheel of Time and Rings of Power. Disney+ bet big on Willow, a series spinning out from one of those 1980s movies. Netflix embraced an animated and irreverent approach to the genre, with Matt Groening sitcom Disenchantment and family adventure film Nimona. HBO is following Game of Thrones with a host of spin-offs. House of the Dragon has already been a massive success.

Emilia Clarke as Daenerys Targaryene in Game of Thrones

The past few years have seen some less fantastical feudal epics, though these tend to be more cynical than their earlier counterparts. Netflix’s recent awards slates included films such as David Mackenzie’s Outlaw King and David Michôd’s The King. Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel was “a medieval #MeToo movie.” Shōgun launched this week on Disney+, the second TV adaptation of James Clavell’s novel. It’s possible to write this off as a Hollywood trend. The studios tend to play “follow the leader”, with any breakout success inspiring a generation of clones. Following the success of Barbie and The Super Mario Bros. Movie, audiences can look forward to about a decade of films and shows based around toys and video games, from Hot Wheels to a Minecraft movie starring Jason Momoa.

While the source material for both Dune and Shōgun predates Game of Thrones, it’s easy to understand why these projects appealed to studios trying to recapture some of that success. These are both deeply cynical stories about the politics of power, rejecting the romantic fantasy that informed earlier pseudo-medieval epics like the Lord of the Rings trilogy or First Knight.

This might hint at a deeper resonance to these more cynical takes on the medieval setting. The past few years have demonstrated that democracy is a fragile thing. Since 2016, the United States has been downgraded by various groups to a “backsliding” or a “flawed” democracy. There are concerns about the spread of authoritarianism in Eastern European countries like Hungary and Poland. Global politics are increasingly dominated by “wannabe fascists” like Javier Milei and Jair Bolsonaro.

While these discussions tend to be framed in terms of fascism, there’s also been an increase in the political power leveraged by both private individuals and corporate entities, which observers like Jodi Dean have described as “neo-feudalism”. Economist and philosopher Yanis Varoufakis argues that the power of modern tech companies that extends beyond the boundaries of capitalism into “techno-feudalism.” Last year, the Rand Corporation claimed global politics was now “a neomedieval world”.

As such, the futuristic feudalism of Villeneuve’s Dune adaptations may not be as abstract as it seems. The past is not just present, it may also be the future.

Join the Irish Independent WhatsApp channel

Stay up to date with all the latest news