I’ve been working in kitchens since I was 13 years old. At the time, I was working as a stock clerk for an organic produce stand in Alameda, CA. The owner of Village Pizza, a slice shop around the corner, came in looking for cremini mushrooms. He was surprised when I started waxing poetic about the quality of the mushrooms, which you could tell, I told him, by the way their tight caps were still fastened to the stem. He asked me if I wanted to come fill in for the dishwasher who missed their shift. Not that a 13-year-old needed a second job but, I was an industrious child with a penchant for earning my own money. So I said yes.

The second I walked into the tiny kitchen of Village Pizza and dipped my hands into the steaming hot sink, I was struck with an exhilarating feeling. The hotter the water, I quickly realized, the faster the grease came away from the pots and pans. I took it as a challenge to get my hands used to the hottest water I could bear. To my surprise, I could bear a lot. It felt good to be good at something. For the next two years, I scrubbed pots and eventually learned how to stretch pizzas and make salads.

By the time I turned 19, I got a job at the original location of Nobu, a fine dining restaurant in the Tribecca neighborhood of Manhattan NY. Just as I did when I stepped foot into Village Pizza, I felt validated. This time in a different way. After years of mixed to little academic success and explaining my rationale for choosing a trade school rather than college, working in a fine dining restaurant was the closest I would ever get to working in a respectable establishment, next to members of what I thought of as high society. I was instantly drawn to the brigade system. The bleached white coats, starched pants, and polished shoes of the kitchen staff gave it a sense of real professionalism. The origin story for every ingredient on the menu and the close relationships with the farmers, rancher, and mongers made it feel noble. Most importantly the impossibly high standards executed with surgical precision made us, from commis to sous, feel like what we did was important. It felt great to be good at something that felt so exclusive. Over the years I made it my mission to work at only the most well renowned restaurants in the world. I worked at Aqua, Joel Robuchon, Eleven Madison Park, and others.

When I started the process of stepping out on my own, at age 30, I did so with the goal of opening another gastronomic temple. I wanted to join the pantheon of chefs like Roger Verge, Joel Robuchon, and Daniel Boulud. But after years of working in fine dining I understood the economics and I knew that I needed a hedge. My hedge would be an adjoining casual Italian taverna that would help take the financial pressure off until I started receiving all those accolades, I was sure would arrive. The taverna, Che Fico, would basically run itself while I poured myself into a 40-seat tasting menu centric dining destination for the global elite.

After I left Eleven Madison Park in 2012 I had the opportunity to travel through Europe to work and eat at some of the most renowned restaurants in the world. When I returned after a year abroad, I made it a point to eat at every fine dining restaurant that I could in the US. So many five-hour marathon meals that consisted of course after course of dishes started to bleed together. I can’t count how many of those meals left me at the end wondering what I actually ate. Literally I couldn’t remember a single dish from some meals. As I sat at a lushly padded table with an ironed double tablecloth, I felt physically ill. I genuinely wished I had gotten up in the middle of my meal and left. I thought that maybe I was just tired of the classic French fine dining with all its gold leaf-coated trappings. But a month later, I felt a similar experience while sitting at a Danish-designed teak table that was devoid of all the obvious luxury ingredients one thinks of when eating at a fine dining restaurant. Handmade ceramic dishes took the place of bone china. Foraged herbs stood in for foie gras. But the emotions I felt were the same. I had seen it before.

I started to think about my own ideas about food. After some time I started to grapple the difficult notion that maybe my own vision wasn’t going to end up differently than those meals I wished I had walked out of. After a year of looking for a space and working out different investment models with my partner, a persistent thought kept creeping into my mind. I was much more excited about the taverna than I was about the fine dining. The numbers looked better too. I was serious about becoming a respected business operator and I wanted to open something financially successful. I didn’t want to become a cliche of the chef who plays business owner just open a short-lived vanity project. Beyond that I wanted to open a restaurant that I actually wanted to eat in.

What I realized is that if I was being honest with myself, I never actually loved the food I was cooking. I loved the respect I got by cooking that food but not the food itself. Every restaurant I had worked at was producing food that was visually stunning and intellectually creative. Most of all it was food that people felt was important. It was so much harder than one would imagine to give myself the “permission” to cook food that I love.

My acceptance came in the form of obsession. Obsessing over a bowl of $38 tagliatelle al ragu. Evan Funke, the award-winning chef of acclaimed restaurants Felix and Mother Wolf gave me a gift by teaching me the craft of rolling pasta by hand and with a large wooden rolling pin called a matterello. Watching Evan roll pasta helped me realize that cooking simple food could be my higher calling. So I went down the rabbit hole. Over the four years it took to open Che Fico, I went to Italy nine times. Over the nine times I visited Italy I immersed myself in every detail. I worked in a butcher shop in Puglia, I made pizza in Naples, I rolled pasta in Bologna, and I ate everything.

When I finally opened Che Fico I realized that It took the same amount of attention to detail to do “casual” food at that level as it did to make fine dining food. In fact, it was harder to be the superlative version of something so many people had experienced before. My fine dining training kicked in and so did my demands for excellence at any cost. In the early days, I rolled every sheet of pasta used for our tagliatelle al ragu myself. It was the iconic dish that spoke to our authenticity and rigorous standards more than any other. It gave me the validation I had sought out in the fine dining Michelin-starred temples of dining and I truly loved it. I loved how it tasted like history in a bowl. I loved how the nuances could take the dish from mundane to spectacular. More than anything, I loved that the skill of rolling pasta by hand was so rare. Italian restaurants were a dime a dozen but, restaurants that could make pasta on that level were few and far in between. It gave me purpose.

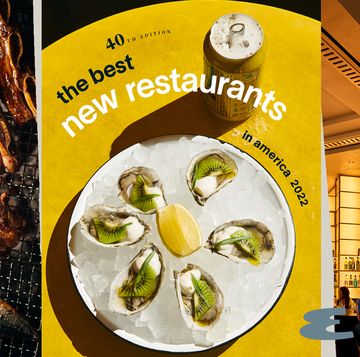

Last year, Che Fico turned five. The food that we serve still excites me and makes me feel like I wish I was eating it instead of sending it to a guest. That's a great feeling. After the past few years, I’ve realized that I can still be excited by fine dining. But it’s rare. It usually happens like a shooting star, unexpectedly. The food that we serve at Che Fico still makes me feel like what we do is important. I have my years spent in fine dining to thank. I realized that the same attention can be given to braised escarole and pizza dough as is given to caviar and Miyazaki beef. Recently the question has been posed: is fine dining sustainable? My answer is no, it’s not but that it's not meant to be. Just as a residency for a doctor or an attorney working at a major law firm isn’t sustainable either. They are training grounds. They are meant to churn out our industry’s version of Navy SEALS, chefs programmed to execute on every detail. Without those years in the trenches of the fine dining temples, Che Fico wouldn’t exist, and neither would our perfect bowl of tagliatelle al ragu but I wouldn’t trade my bowl of pasta for anything.