What Is Hyperinflation?

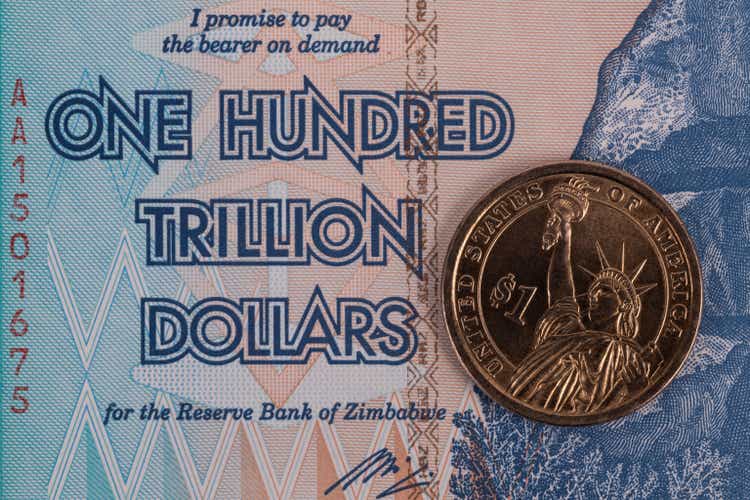

Hyperinflation is a monetary condition of exceptionally high rates of inflation, often defined as monthly inflation rates of 50% or greater.

The root cause of most hyperinflations is when governments print money to address their budget deficits.

Events such as wars, natural disasters, or the breaking of pegged foreign exchange rates can lead to or amplify hyperinflationary periods.

Looking for a helping hand in the market? Members of Ian's Insider Corner get exclusive ideas and guidance to navigate any climate. Learn More »

Max Zolotukhin/iStock via Getty Images

What Is Hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is a monetary condition when a country experiences an exceptionally high rate of inflation as measured by a consumer price index or other similar metrics. Economist Phillip Cagan wrote The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation in 1956, which is viewed as one of the first serious investigations into the phenomenon of hyperinflation. Cagan defined hyperinflation as a monthly inflation rate of 50% or greater, which amounts to a more than 10,000% annualized inflation rate.

More recently, some analysts have used the term hyperinflation to apply to much smaller inflationary events. Today, hyperinflation often refers to countries that are experiencing at least 100% annualized inflation rates.

Hyperinflation is not a synonym for a merely elevated inflation rate compared to the recent historical norm, but rather a time when a country's monetary system becomes entirely dysfunctional and leads to widespread chaos throughout the economy.

What Causes Hyperinflation?

Economist Peter Bernholz, using Cagan's definition of hyperinflation, found that 25 out of 29 historical hyperinflationary events were provoked by money printing that was used to fund government budget deficits. That tends to be the root cause of most hyperinflations, though there can be individual differentiated catalysts such as war or natural disaster that cause a government to turn to money printing as a solution for its financial troubles.

It's important to note that typical incidences of garden-variety high inflation, such as stagflation or demand-pull inflation, usually don't escalate to hyperinflation. Large developed economies such as the United States or United Kingdom sometimes see their inflation rate spike to 10% or even 20% per year due to these inflationary effects.

However, it generally takes a far sharper catalyst to go from merely elevated inflation to a hyperinflationary event where a currency loses virtually all of its prior value. After all, hyperinflation is nowadays thought of as a rate of 10% or more per month. That's an exponential difference to merely high inflation. During a true hyperinflation, retail establishments raise their prices every week or even every day (sometimes afternoon pricing is higher than morning pricing!) and all semblance of having a stable economy disappears.

So, what causes these true hyperinflationary storms?

Money Printing & Large Budget Deficits

To put it simply, hyperinflation usually occurs because a government can't fund its obligations from taxation alone and instead prints new money out of thin air to fill the fiscal hole. When the government creates a large amount of new monetary supply out of the ether, it reduces the value of currency that is already in circulation. It also does away with the idea of using that currency as a store of value.

People using a currency that is being actively debased will seek to spend it immediately before it loses additional purchasing power or convert it into a secure store of value such as gold or a more reputable currency like the Swiss Franc or U.S. Dollar.

War & Reparations

One of the most famous hyperinflationary incidents in history was that of Germany following World War 1. Prior to the beginning of that war, the German Mark traded around five to the dollar. By 1923, the German Mark had fallen to an exchange rate of approximately a trillion to a dollar, and a wheelbarrow full of currency could not buy a loaf of bread or even a newspaper.

A large factor in the abrupt plunge in Germany's currency was the war. The war damaged a large chunk of Germany's industrial capacity, limiting that economy's ability to generate taxes in the immediate aftermath of the conflict. Additionally, Germany was required to pay a large portion of its economic output as war reparations on a go-forward basis.

Given the weakened state of its economy and labor force, it wasn't able to collect enough funds to make good on these reparation debts through normal means, and instead turned to simply printing up fresh marks to fill the gap. As Germans realized that their currency would no longer be a stable store of value, they rushed to spend or convert their marks as soon as they got their paychecks, leading to an historic bout of capital flight and hyperinflation. The hyperinflation finally ended when the currency was abandoned and the country adopted a new currency, the Rentenmark, to replace the old paper mark.

Germany is far from the only country that fell into such a hyperinflationary spiral following war. At its heart, hyperinflation is driven by a government spending much more on its expenses than it can generate in taxes. As war tends to be one of the costliest things that government engages in, it is a prime cause of many economic shocks.

Breaking Of A Foreign Exchange Peg

A common event during a hyperinflationary period is the breaking of a foreign currency peg. Countries may choose to peg their currency to a foreign one, such as the U.S. Dollar or Euro, in order to benefit from their monetary credibility, fiscal policy, improved trade status, or other such advantages. For small countries or ones with a volatile economic history, a foreign exchange peg can sometimes offer more stability than a free-floating currency.

However, these pegs can amplify problems when an economy runs into trouble. That's because a country's central bank has to defend the given foreign exchange level even as prices in the economy are rapidly moving away from that pegged level. This often ends with the central bank running low on funds to defend the fixed exchange rate, leading to a sharp and chaotic devaluation of the currency when the peg is finally broken. This can cause citizens to rush to abandon the domestic currency, generating another wave of inflation and capital flight.

To give one recent example, Lebanon had a low inflation rate until around 2020. Between 2020 and 2022, the annual inflation rate started to soar, topping 100% in 2021. In February 2023, the Lebanese Central Bank officially devalued the Lebanese Pound by about 90% compared to the U.S. Dollar. The Lebanese inflation rate spiked from about 120% annually prior to the move to more than 250% shortly thereafter, pushing Lebanon deep into a hyperinflationary event.

Preparing For Hyperinflation

Countries with long histories of stable economic policy rarely fall into hyperinflation overnight. Rather, it tends to countries with a track record of massive fiscal deficits, incoherent monetary policy, and rising price instability that eventually lose control and give in to money printing and a complete debasement of their currencies. That is to say that while hyperinflation remains a potential problem for some smaller economies or places with grossly unsound central banking practices, the odds are low that well-established and successful economies such as those of the United States, Canada, Japan, or Australia would experience hyperinflation in the near future.

That said, though it may be unlikely, investors can take steps to hedge their portfolios against the risk of hyperinflation. Owning hard assets such as farmland, real estate, or gold is one common tactic for dealing with monetary debasement. International diversification is another solid approach, as it lowers the geographic concentration of an investor's portfolio to any one particular currency and economy.

Impacts Of Hyperinflation

When a country experiences hyperinflation, its citizens tend to act differently as it relates to money. In Argentina, for example, there have been several bouts of hyperinflation historically. This has led to many transactions in the economy, such as for real estate, being priced in dollars even though the government encourages people to use the Argentine Peso. Argentines are loathe to keep large sums of money in local banks and often put their deposits for safekeeping in international banks. Argentines also often exchange their pesos for dollars as soon as they receive a paycheck in order to maintain their purchasing power. Countries with hyperinflation such as Argentina and Venezuela have also been among some of the more active adopters of cryptocurrency as another means of sheltering their wealth.

All told, hyperinflation creates a dramatic negative impact on the economy. People are afraid to engage in routine financial transactions such as opening savings accounts or signing long-term contracts for fear of the financial repercussions of a rapidly devaluing currency. This creates substantial economic friction and often leads to magnified problems generating the economic growth and resulting tax base necessary to escape from a financial crisis.

Bottom Line

Hyperinflation is a rare and acute state of monetary disorder that leads to crippling effects for the countries in which it occurs. Fortunately, most countries won't have to worry about hyperinflation, as it only tends to come about due to extreme levels of money printing when a government or central bank gives up any pretense of sound policymaking.

Regardless, investors can take prudent steps to protect their assets from a potential hyperinflation by owning a variety of real assets while diversifying their equity and fixed income holdings across a number of different countries and currencies.

This article was written by

Ian worked for Kerrisdale, a New York activist hedge fund, for three years, before moving to Latin America to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities there. His Ian's Insider Corner service provides live chat, model portfolios, full access and updates to his "IMF" portfolio, along with a weekly newsletter which expands on these topics.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha's Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.