KRE: The Fed Wants Large Banks To Consume Smaller Ones

Summary

- Regional bank stocks have experienced a recovery but have recently dipped, raising concerns about another wave of losses.

- Off-balance sheet losses and unrealized losses on loans and securities are causing significant strain on regional banks' equity.

- Negative trends in net interest margins, deposit rates, and credit growth are impacting regional banks' performance and outlook.

- Should inflation rebound with the energy market, the Federal Reserve cannot supply any meaningful stimulus to struggling small banks.

- Manufacturing data, consumer surveys, and lending trends suggest that most households, companies, and banks are acting as if the US is in a recession.

Manuel-F-O/iStock via Getty Images

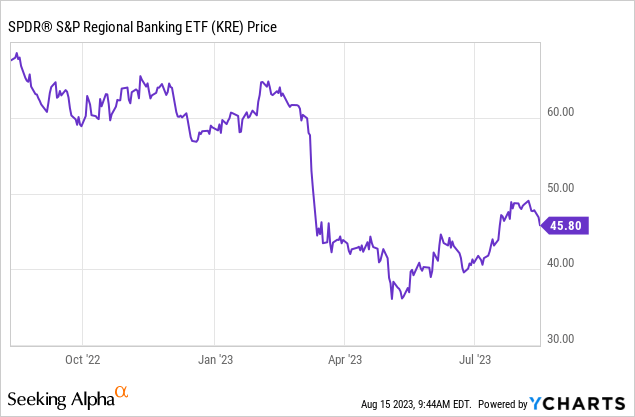

The regional bank crisis earlier this year spiked a wave of concern across financial markets. Regional banks lost around 20% of their value this year, as indicated by the regional bank ETF (NYSEARCA:KRE). The crisis was triggered by an initial liquidity shortage amongst a few smaller banks with excessive off-balance sheet losses and significant deposit outflows. To a large extent, the situation was triggered by widespread concerns over uninsured deposits, causing many companies with uninsured deposits to pull money out quickly, forcing numerous banks to go under.

Since First Republic's (OTCPK:FRCB) failure, regional bank stocks have been very quiet, with KRE rising by over 25% from its May trough. The US government, specifically the Federal Reserve, enacted numerous policies to stop the crisis from growing. This includes offering a "Bank Term Funding Program" that offers discount-rate debt backed by the par value of Treasury and agency bond assets, pausing interest rate hikes (mainly due to disinflation), and potentially expanding the FDIC to cover all deposits. While these efforts promoted a solid recovery for KRE, the ETF has taken a notable dip over the past week, losing around 6-7% of its value. See below:

As KRE dips back lower, many investors will likely ask themselves if it is a recovery dip-buying opportunity or a sign of another wave of losses. To better understand the regional bank situation today, we must consider the core causes of their headwinds in light of the government's actions to stem the strains. Further, we must consider potential discounts should interest rates decline or lose if the yield curve rebounds without interest rate cuts. Finally, most of the performance changes from KRE may be bound to economic trends; if loan losses or loan loss risks rise above current levels, then KRE could face headwinds on multiple fronts.

Any Discounts in Regional Banks?

Problematically, at the end of 2022, based on an in-depth paper, banks in total had roughly $780B in off-balance sheet losses due to increases in long-term interest rates, negatively impacting the fair value of their mortgage-backed-security assets. That figure equates to around 28-36% of total bank equity. Unrealized loss estimates rise to a staggering $1.7T if the change in the fair value of bank loans is accounted for, equating to around 77% of total bank capital ($2.2T).

Long-term interest rates, such as mortgage rates, have risen by 25-50bps since the beginning of the year, so total unrealized losses today are likely higher than in December 2022. Accordingly, if all banks today closed their books and looked to sell assets to each other at fair value, they would be left with little to no equity. Most focus has been on securities losses since those are far more liquid assets than loans. Still, the total unrealized losses on loan books are likely higher, particularly for those banks with significant fixed-rate loan portfolios. With this in mind, investors should not emphasize a bank's price-to-book ratio too much because their book value is likely far above its actual liquidation value.

The Federal Reserve has primarily offset the risk of unrealized securities losses by offering loans against the par value of those securities. This provides bank liquidity needed to counteract such losses; however, it is causing banks to increase their leverage and borrowing costs as assets decline to be offset by new liabilities. Overarching negative trends on deposits will likely continue over the coming year unless QT policies are ended, while deposit rates should continue to rise. Further, the longer the yield curve remains inverted, the more banks should see net-interest-margin declines as their swap hedges expire. Accordingly, while the "crisis" is no longer at excessive risk of becoming fast-moving, most of the core causes of the issues remain.

I believe investors should not consider book-value discounts on KRE's holdings because book values are so far above liquidation equity values. However, KRE's price-to-earnings ratio is lower at 8.25X, with its forward "P/E" at 9X, but that is not too low for banks considering they carry much higher cyclical risks than other industries. Further, as seen in the "P/E" difference in its forward valuation, the EPS outlook for banks is negative due to strains on net interest income. Banks have had very high net interest margins over the past year as their assets are generally variable rates while deposit rates have slowly risen. In general, smaller regional banks are seeing much faster increases in deposit rates as they compete for a smaller supply of deposits. Additionally, smaller banks with liquidity strains borrow more from the Federal Reserve, usually at higher interest rates than their deposit costs.

The negative impending NIM trend is seen in the spread between bank prime loan rates and short-term CD rates. CD rates were slow to rise initially last year compared to prime loan rates, causing excessive NIM growth for most banks. However, prime loan rates should not increase as long as the Federal Reserve maintains rates, while CD rates are rising exceptionally quickly due to deposit declines. See below:

This is the most significant negative factor impacting net interest margins and is particularly substantial for KRE's holdings because many regional banks have had to increase deposit rates to 5% over recent months to maintain deposits. Besides Citi (C), large banks have kept deposit rates near zero, implying depositors are particularly concerned about depositing in regional banks.

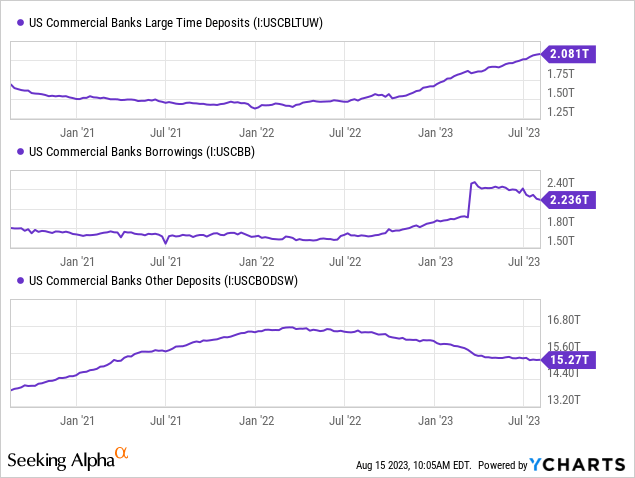

As a result, banks have seen negative trends in deposits, particularly in savings deposits, mixed with an increase in higher-cost large-time deposits. Banks also saw a massive rise in non-deposit borrowing earlier this year due to the liquidity crisis, with that figure reversing today. See below:

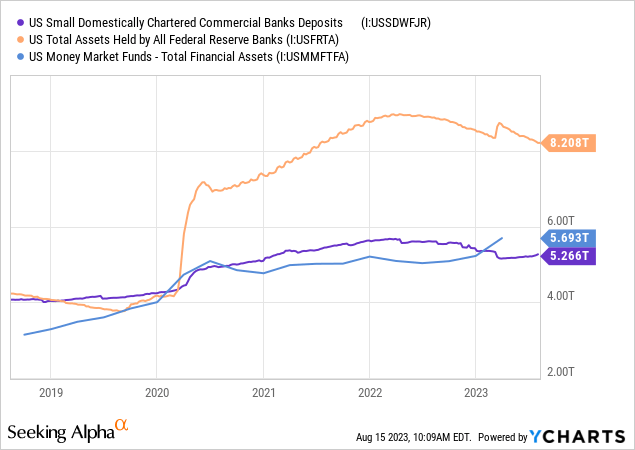

The increase in non-deposit borrowings and large-time deposits should increase banks' total borrowing costs beyond increases in savings rates. The Federal Reserve's quantitative program ultimately drives the overarching trend in bank deposits. In 2020, the Fed pushed extreme cash into banks by purchasing Treasury assets. Banks also purchased Treasury assets, which the Fed is now selling at a notable loss via its QT program. As the Fed sells bonds, cash is functionally deleted from the economy, pushing a negative trend in bank deposits. Small banks have been disproportionately impacted as cash-holders lower deposits and increase money market savings, which pays a higher yield. See below:

In recent months, small bank total deposits have risen, primarily driven by the increase in large time deposits, with total other deposits stabilizing. Over that period, many small banks have dramatically increased deposit and savings rates to the 4-5% level, making them far more competitive with money market funds. Most likely, there have been some declines or stagnation in money market funds as smaller banks regain some deposits. However, the much more significant trend impacting the total US money supply remains negative as the Federal Reserve continues removing money from the economy. This trend temporarily reversed earlier this year due to the bank term funding program (seen in the bank's "other borrowings" and total Fed assets); however, that trend has reversed mainly due to the term limits on those loans.

Bank Leverage is Higher Than Understood

Overall bank leverage has remained nearly unchanged over recent months, with slight leverage declines for small banks. However, the significant caveat is that bank leverage measures, including the popular CET1 ratio, account for assets at par value and not at fair value (besides those available for sale). For example, Silicon Valley Bank had one of the best CET1 ratios on the market and could easily pass Fed stress tests before its sudden failure because the Fed and Basel rules completely overlook off-balance sheet losses. As mentioned earlier, total off-balance sheet losses on banks' loans and securities nearly equal bank equity. In reality, most US banks probably have equity of around 2% of assets if assets are counted at fair value. That can be calculated by bank "equity" ($2.2T) minus unrealized losses ($1.7T), or ~$500B over total bank assets of $22.8T, even less if preferred equity and intangible assets are removed.

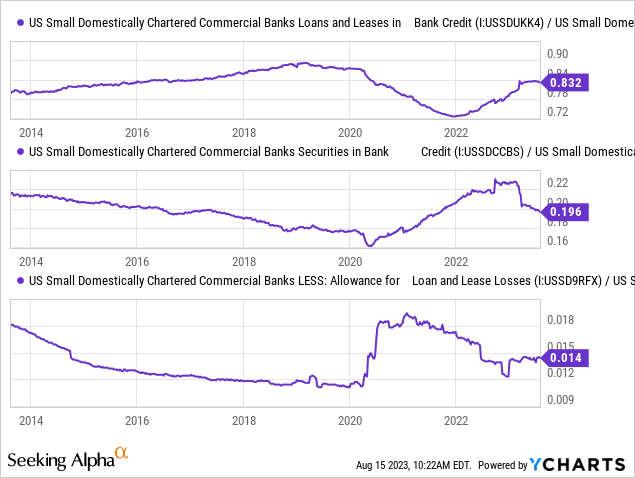

With that in mind, as a whole, US banks are operating at maximal potential leverage today and cannot continue to increase loan portfolios, mainly if loan losses grow. In recent months, smaller US banks have rapidly reduced securities assets while stopping the expansion of loan-to-deposit ratios. Loan loss estimates remain low at 1.4%, down from ~1.9% in 2020. See below:

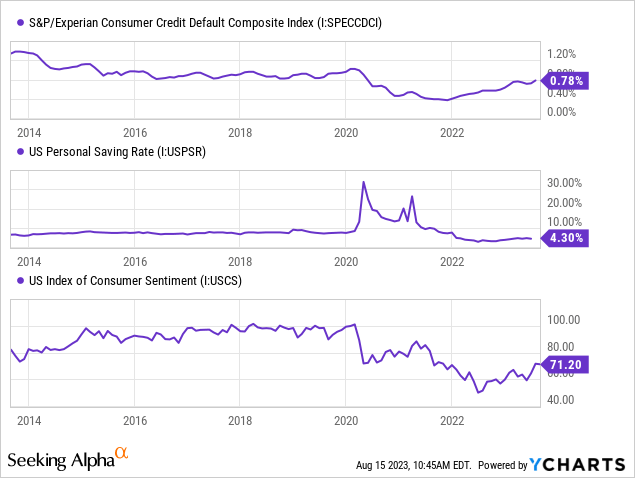

Overall, banks, both large and small, are halting credit growth. Total loans and leases have remained around $12T since the banking crisis began in March. In general, stagnation in total bank lending is a signal of a negative credit cycle. As banks slow lending, it becomes more difficult for companies and households to borrow new money, often causing some to fail to refinance, usually ending in higher default rates. Default rates are generally low today as they were suppressed by QE activities in 2020, but they have risen quickly this year. As indicated by lower-than-normal savings and consumer sentiment, consumer defaults are back near normal levels but may soon rise above those levels. See below:

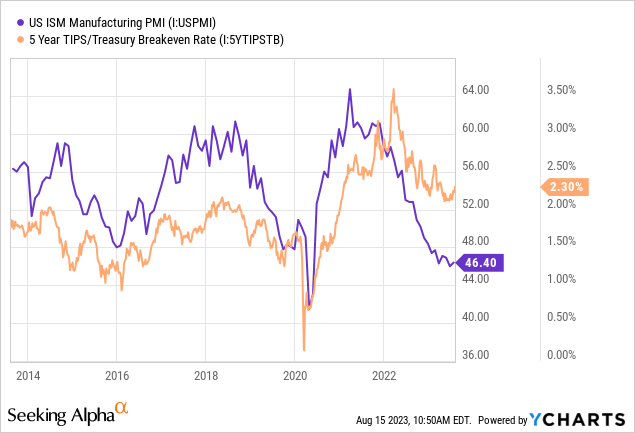

Many households continue to struggle with falling wages after inflation. The overall job numbers have been good, but higher-paying jobs have been much harder to find, while lower-paying ones are seeing more robust growth. This trend may soon reverse due to the rapid decline in business activity in the manufacturing sector this year. The manufacturing PMI currently sits at its lowest level since 2020, giving manufacturing companies the weakest outlook since then, which is also the worst since 2008 if 2020 is excluded. The inflation outlook, which is tightly correlated to the PMI, declined in 2022 but remains very high compared to the manufacturing PMI. To me, that is a strong indication that inflation is only lower due to a sharp slowdown in the manufacturing sector. See below:

The inflation outlook rose recently due to a sharp increase in oil and gasoline prices, which I expect to continue due to largely non-economic reasons (primarily geopolitical). If so, the inflation outlook could rise even if the economic outlook continues to falter, likely causing significant yield curve steepening that further harms banks' NIMs. On top of that, the sharp declines in manufacturing activity, combined with weak consumer strength, should result in higher loan losses. Banks, notably smaller regional banks, do not have sufficient liquidity should that occur, particularly considering the sharp increase in their borrowing costs.

Notably, large corporations have not seen significant increases in credit risk. However, small businesses declaring bankruptcy are near a record high today. Recent trends indicate this issue is spreading to larger consumer discretionary and manufacturing companies. Larger companies have had significant debt growth since 2008 but were not impacted because they often could refinance at lower interest rates. Now that rates are much higher, many companies will need to pay off debt, with the market facing a huge "debt maturity wall" over the 2023-2025 timeframe. Once again, we see another example of a significant potential bank risk that has existed "under the rug" for years now coming to the surface amid higher interest rates.

The Bottom Line

Ultimately, most investors will believe what they wish to think regarding the stability and outlook of the US banking system. In my experience, the allure of discounts is a significant blinder to the risk factors facing banks. However, if we account for a sharp decline in regional banks' net interest income outlook and significant unrealized losses (likely accounting for most book value), it is tough to justify banks as undervalued or discounted. Indeed, given the most recent rise in regional banks, I believe most are trading well above their liquidation equity value and will face dividend cuts amid lower EPS this year and next. The sharp increase in deposit costs should significantly accelerate that trend.

Of course, KRE and its constituents would be undervalued only if we could definitively say that long-term interest rates will be reduced and that the Federal Reserve will cut rates. Both of those will occur without a recessionary increase in loan losses. In my view, all three of those factors need to be true for regional banks to be a buying opportunity today, and it is hypothetically possible that that could be the case. However, in my opinion, it is much more likely that interest rates will remain elevated due to the inflationary factors in the energy market, even if a recession occurs. Further, even if energy prices do not create upward inflation pressure, it is almost always historically the case that loan losses rise during recessions, offsetting potential benefits from recessionary interest rate cuts.

Accordingly, a "typical" gentle recession is not necessarily bearish for KRE. Still, a recession combined with resilient inflation almost certainly is because the Federal Reserve could not aggressively stimulate in that scenario. In my view, the data, and the lived experience of most Americans, points strongly toward a stagflationary recession that could be very problematic for regional banks due precisely to their competition for deposits. For this reason, I continue to have a bearish outlook on KRE and believe it will decline amid further increases in bank failures, which cannot be aided by government intervention. My bearish outlook is more specific to regional banks in KRE, as larger banks, such as JPMorgan (JPM), should fare much better because its capitalization allows it to buy regional banks' assets at a discount. Indeed, my long-term view is that the US banking system is headed for significant consolidation that could leave the US with a much smaller number of banks, similar to the pattern after 2008.

This article was written by

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha's Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.