QQQ: The Capex Boom May Turn To Bust Amid Savings Shortage

Summary

- The current tech sector capex boom seems at risk of turning to bust due to the lack of real savings available to sustain it.

- Capital expenditure over the past 12 months has grown by 23% to USD350bn, reaching 9% of sales and almost half of operating cash flows.

- Declining US national savings and rising real borrowing costs are the conditions under which malinvestment has been known to occur in the past.

- I remain short the QQQ, which tracks the Nasdaq 100.

Andrii Dodonov/iStock via Getty Images

I have written a lot about the Invesco QQQ Trust ETF (NASDAQ:QQQ) in recent months as I believe we are in a bubble that rivals the dot com bubble and will end in similarly poor returns for investors. I noted last month that the Nasdaq 100 rally contrasts with the collapse in unadjusted earnings and free cash flows. In this article, I will focus more specifically on why I believe the current capex boom is at risk of turning to bust due to the lack of real savings available to sustain it.

I am increasingly bearish on the QQQ ETF, which is the largest and most liquid ETF tracking the Nasdaq 100, with $200bn in assets, and having tracked the NDX with virtually zero tracking error since 1999. The QQQ differs from the QQQM only in that its expense ratio is 0.2% versus 0.15%, but as I am short, this extra fee works in my favour by having a slightly lower dividend yield.

Paper Profits Vs Real Wealth Creation

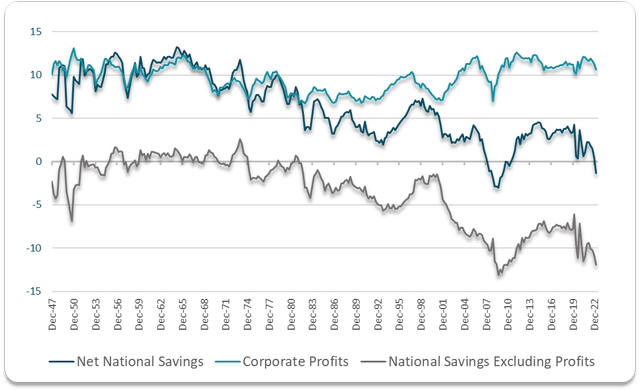

Despite falling over the past year, NDX profits remain 43% above pre-Covid peak levels at $530bn. While this represents just 2% of total US GDP, it makes up over 20% of total US economy-wide corporate profits, up 5pp from pre-Covid levels. High profit margins theoretically indicate a high degree of savings in the economy as profits in any given period are simply the national savings in that period that accrue to the corporate sector. However, what is remarkable about the post-Covid profit boom is that it has occurred alongside negative US savings.

Savings, % of GDP (Bloomberg, Author's calculations)

This suggests that the non-corporate sector must be drawing down its savings, which is happening as a result of the large government deficit. By subsidizing wages via transfer payments, consumers have been able to consume far more than their wages would otherwise allow, in turn allowing corporate revenues to far outstrip wages.

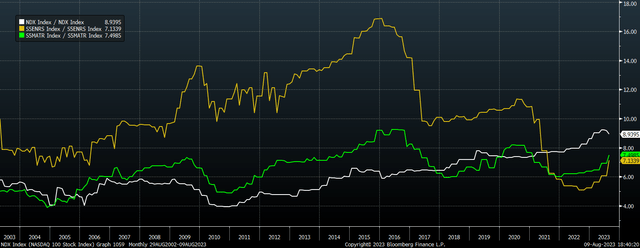

I think the problem facing the US corporate sector, and the tech sector in particular, is that the paper profits generated since Covid now must be spent on capital investment to sustain future growth, yet real economy-wide savings are shrinking. Tech companies are now finding out that the purchasing power of these paper profits in the real market for investment goods is declining, as reflected by the surge in capital spending. Capital expenditure over the past 12 months has grown by 23% to USD350bn, reaching 9% of sales and almost half of operating cash flows.

The surge in capex in the tech sector contrasts greatly with the decline in capex in the resource sector, where increased output is needed to fuel future economic growth. While capital has flowed aggressively into the tech sector, ESG concerns have meant resource companies have shifted away from capital investment and towards shareholder returns through dividends. This creates the potential for a further rise in resource prices over the coming months and years that could further undermine tech sector profitability.

Capex/Sales Ratio: NDX, SPX Energy, and SPX Materials (Bloomberg)

External Savings May Become Harder To Attract

The US is currently able to invest more than it saves by borrowing internationally as reflected by its current account deficit. The economy's reserve currency status affords the US access to international resources in exchange for relatively low-interest debt. Another country with the same lack of savings would likely be forced via currency weakness to consume less and save more. However, this exorbitant privilege should not be taken for granted, particularly with fiscal deficit projections becoming increasingly unsustainable and the US's net international investment position at a deficit of over 60% of GDP. Any loss of confidence in the dollar among foreign or domestic investors would drive up import costs and profits.

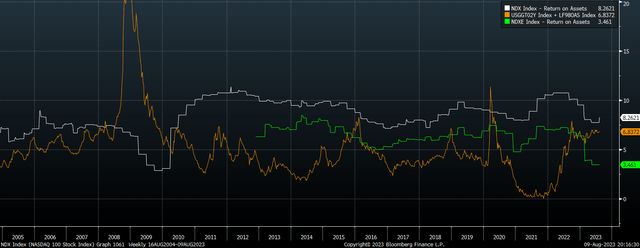

Rising Real Borrowing Costs An Additional Threat

An additional threat facing the tech sector capex boom comes from the rise in real borrowing costs. Even with a strong risk appetite keeping credit spreads narrow, the yield on 2-year high-yield corporate bonds is now almost 7% above 2-year inflation expectations, which compares to the Nasdaq 100 return on assets of around 8%. For the median Nasdaq 100 stock, ROA is now significantly below borrowing costs.

ROA For NDX and NDXE Vs Real High Yield Corporate Bond Yield (Bloomberg)

Extreme Valuations Amplify The Downside Risk

The fact that tech sector profits far exceed national savings would not nearly be as concerning if the multiple that investors were paying for these earnings offered a margin of safety against falling profits. In contrast, the Nasdaq 100 offers an earnings yield of below 3% and a free cash flow yield of 2.5%, the latter being 40% and 2 standard deviations below its 20-year average. With sales growth slowing in line with the overall economy as I noted in July, I believe fair value is fully 80% below current levels.

Such extreme valuations are problematic from the perspective of long-term returns, to say the least, but it also raises the risk that the current investment boom will result in a bust and further widespread profit declines. The reason being that during bubbles when equity is cheap and access to credit is easy, businesses tend to be rewarded by investors for making aggressive investments will less scrutiny than in typical market conditions, resulting in malinvestment. In today's market, investors are rewarding the huge capex associated with Artificial Intelligence, which is why semiconductor stocks are trading at more than 5 times the valuation of resource stocks.

Could An AI Productivity Boom Justify Valuations?

Most major investment bubbles are driven by some form of game-changing technology. The improvements in communication due to the widespread adoption of the telephone helped fuel the 1920s bubble, while the adoption of the internet helped drive the 1990s bubble. The main risk to my bearish thesis on the tech sector is that the productivity enhancements from AI are strong enough to allow earnings to grow into their valuations.

Some have argued that its impact on productivity will be 'bigger than the internet'. Considering that Nasdaq 100 earnings per share rose by around 10% per year in the two decades that followed the dot com peak, similar growth going forward may justify current valuations. However, with tech sector revenues now representing one-quarter of total US equity market revenues and 14% of GDP, almost 4x larger than in 2000, I am skeptical about the extent to which technology adoption can continue to allow tech sales and earnings to outperform unless it can raise US productivity growth. It is worth noting that while certain companies and sectors have benefitted greatly from the internet's mass adoption, it did not alter the long-term decline in US productivity growth.

Summary

While there is no way to know ex ante if the current tech sector capex boom will ultimately prove to be profitable or not, declining US national savings and rising real borrowing costs are certainly the conditions under which malinvestment has been known to occur in the past. This is a problem considering that valuations are at extreme levels. An AI driven productivity boom is the main risk to my bearish view, but as we have seen following previous bubbles, investors tend to bid up stocks to valuations that result in poor long-term returns even when earnings grow strongly.

This article was written by

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial short position in the shares of QQQ either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha's Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.