We Are (Almost) All Investing Incorrectly

Summary

- The herding effect in financial markets is influenced by factors such as rational decision-making, psychological biases, institutional influences, biological processes, and adaptive strategies.

- Different economic schools of thought, including classical, Keynesian, behavioral, Austrian, complexity, institutional, neuro, evolutionary, post-Keynesian, socio, and information economics, offer unique perspectives on the herding effect.

- To navigate the complexities of the global economy, investors should focus on long-term trend following techniques or income investing and ignore complex economic commentaries.

monsitj

Even apart from the instability due to speculation, there is the instability due to the characteristic of human nature that a large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits – of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.

--Sir John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes: The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

Sir David Ricardo once advised investors to let the winners run and to cut losses quickly.

I would argue that if you have a fixed amount of capital, any other advice is noise.

Ricardo further elaborated: “I play for small stakes, and therefore if I’m a loser I have little to regret." Sir David Ricardo was not a mere intellectual. Unlike most professional economists, he amassed a huge fortune trading for his own account, and purchased Gatcombe Park, which is now owned by Princess Anne.

Gatcombe Park (Wikipedia.org)

Far before Sir John Maynard Keynes' famous observation of "animal spirits," Ricardo was well aware of the herding effect in financial markets. We must survive a series of uncertain present states in order to take advantage of opportunities in the future. Therefore, keeping losses small is essential. Keeping upside open-ended is also essential.

Ricardo's words are brilliant, because not only are they an implicit recognition of the herding effect, but they also give us mathematically sound advice on how to deal with it.

Most of us do not have Warren Buffett's positional advantage of having billions coming in each month due to the payment of insurance premiums, which we must put to work. These premiums give Berkshire the ammunition to keep buying almost indefinitely, and indeed, to take over a company which it deems to be undervalued.

Most investors have very fixed asset bases which they need to protect. Therefore, heed Ricardo's advice.

In addition to investors' natural tendency to act in a herd, central bank gambits to inject and to withdraw liquidity create trends, or serial autocorrelation, in the direction of asset classes. This further exaggerates the natural herding behavior of index investors, heightening this natural tendency to a fever pitch.

In addition, popular narratives around technological progress and societal change also fuel the herding effect.

We can see examples of this in the internet bubble of the 1990s and subsequent bust in 2000, the great financial crisis of 2008-2009, and the current focus on society-changing advances in AI.

These popular narratives can create multi-year booms and subsequent busts, further strengthening the herding effect in financial markets.

Over time, the interplay of these causes creates a massive herding effect.

The intellectual history of the herding effect is equally fascinating as we view it through different economic schools of thought.

The herding effect, characterized by the tendency of individuals to mimic the actions of a larger group, has long been a subject of interest in economic literature. Different economic schools of thought interpret the herding effect through unique lenses, each contributing to a richer understanding of the potential causes of the phenomenon.

Classical Economics

Classical economics, based on laissez-faire principles, presumes market participants as rational actors. From this perspective, the herding effect can be seen as rational when individuals lack complete information. People often rely on the decisions of others in the market, under the assumption that those decisions are informed, thereby contributing to the herding effect. However, the classical school typically regards this as an exception rather than the norm, as it assumes markets to be efficient and the actors to act independently based on available information.

Keynesian Economics

Keynesian economics, rooted in the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, suggests that market participants are driven by psychological factors, which Keynes referred to as "animal spirits." From a Keynesian perspective, the herding effect can be a manifestation of these animal spirits, particularly the propensity to follow the crowd. In uncertain economic conditions, individuals might follow the majority's actions out of fear or optimism, leading to herd behavior. This behavior could further intensify economic booms and busts, contributing to economic instability.

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics combines insights from psychology and economics to explain economic decision-making. It acknowledges that individuals are not always rational and are subject to various cognitive biases. Behavioral economists view the herding effect as a result of these biases. They argue that individuals often exhibit 'groupthink' or conformity bias, leading them to follow the actions of a group rather than making independent decisions. This school of thought also emphasizes the role of information cascades, where people base their decisions on observing others, contributing to the herding effect.

Austrian Economics

Austrian economics, with its emphasis on individual action and subjective value, offers another lens through which to view the herding effect. Austrian economists argue that herding behavior might occur in response to economic policies that create artificial booms or busts. For instance, expansionary monetary policy might lead to a rush of investments in certain sectors, creating an illusion of profitability and causing investors to follow the crowd into these sectors. Austrian economists caution that such herding can lead to malinvestment and subsequent market corrections.

The herding effect, while being extensively discussed and analyzed from the viewpoints of the Classical, Keynesian, Behavioral, and Austrian schools of economics, also finds a place in more contemporary and interdisciplinary approaches.

Complexity Economics

Complexity economics, which views the economy as a complex adaptive system, interprets the herding effect in terms of interconnectedness and feedback loops. According to this perspective, individual decisions, influenced by the actions of others, can have cumulative effects leading to emergent behavior at the macro level. The herding effect is thus seen as a systemic outcome that emerges from the complex interplay of individual decisions, information flows, and market structures.

Institutional Economics

Institutional economics, focusing on the role of institutions in shaping economic behavior, provides another lens to analyze the herding effect. This school of thought posits that institutions and social norms can strongly influence individual behavior, leading to conformity and herding. For instance, corporate culture, regulations, and industry norms can influence investment decisions, causing market participants to move in tandem. In this context, the herding effect is an embodiment of institutional influences on economic behavior.

Neuroeconomics

Neuroeconomics, a nascent field that combines neuroscience, psychology, and economics, presents a novel angle to understand the herding effect. From this perspective, the herding effect is seen as a consequence of our brain's decision-making processes. Studies suggest that social conformity activates the same regions of our brain associated with reward processing, implying that following the crowd might be neurologically rewarding. This biological insight further underscores the power of the herding effect in economic contexts.

Evolutionary Economics

Evolutionary economics, which applies the principles of evolution like variation, selection, and adaptation to economic phenomena, may view the herding effect as a survival strategy. In uncertain environments, following the majority may increase the chances of survival, as the collective wisdom of the group can outweigh individual knowledge. Consequently, herding behavior can be seen as an adaptive strategy in response to market uncertainties.

Post-Keynesian Economics

Post-Keynesian economics, which builds upon and diverges from some of Keynes' ideas, posits that uncertainty is an inherent and irreducible aspect of economic life. This school believes that in times of uncertainty, individuals are likely to resort to conventional behavior or norms, including herding, as a defensive response. According to Post-Keynesian economists, such convention-driven herding behavior can give rise to financial instability and can even fuel financial crises.

Socioeconomics

The socioeconomic approach, which integrates economics with social sciences, views herding effect as a socio-cultural phenomenon. It highlights how social influence and cultural norms can drive economic behavior. For instance, societal pressure to conform can lead individuals to follow popular consumption or investment trends, thus contributing to the herding effect.

Information Economics

Information economics, which studies the role of information in economic decisions, views the herding effect as an outcome of information asymmetry and cascades. When individuals have limited information, they tend to observe and follow the behavior of others, leading to information cascades that can create and enhance the herding effect. Herding in this view is an adaptive response to an environment where obtaining and interpreting information is costly.

The herding effect, as viewed through the lenses of different economic schools of thought, provides a rich tapestry of insights. Each perspective offers unique understanding and implications. The ongoing study of these perspectives is crucial to further our understanding of the herding effect and its consequences on financial markets and economic stability.

The diverse perspectives on the herding effect offered by various economic schools of thought – both traditional and contemporary – testify to the complexity of this phenomenon. It’s clear that the herding effect is not merely a characteristic of irrational behavior but rather a complex economic occurrence influenced by factors as varied as rational decision-making, psychological biases, institutional influences, biological processes, and adaptive strategies. Understanding these diverse influences on herding behavior can provide valuable insights for policy-makers, investors, and regulators as they navigate the intricacies of the global economy.

Its presence, whether viewed as a rational response to incomplete information, a consequence of animal spirits, a product of cognitive biases, a reaction to economic policy, an emergent behavior in complex systems, an institutional influence, a neurologically rewarding strategy, an evolutionary survival technique, a defense against uncertainty, a socio-cultural phenomenon, or an information cascade, underscores the diverse influences at play in economic behavior. However, almost all economic schools of thought recognize that the herding phenomenon exists. They just differ on why.

As we explore human decision-making in economic contexts, these perspectives can collectively guide our understanding of the herding effect. However, we must also create a competitive response to this phenomenon to guide our own behavior. Sir David Ricardo's advice to let the winners run and to cut losses quickly is optimal. It should guide our competitive response to the herding phenomenon.

Algorithmic methods can often sniff out important statistical footprints created by the herding effect. Investors ignore the trends created by the animal spirits of the herding effect at their own peril.

The Zomma Directional Algorithm is designed to capitalize on trends that emerge from the investment flows caused by herding behavior.

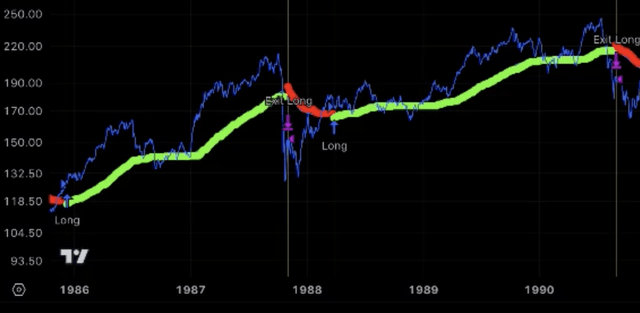

Here's how to understand the visualization:

1. When the line turns green, it signals a buy.

2. When the line turns red, it signals a sell and a move to cash.

Note: The algorithm is not designed to create short signals.

The herding effect in the Nasdaq-100 index has been remarkable since the creation of the index in the 1980s.

It is remarkable that even the Black Friday crash of 1987 did not wipe out the Nasdaq-100's gains from 1986.

Nasdaq 100 from 1986 (www.ZommaEngine.com)

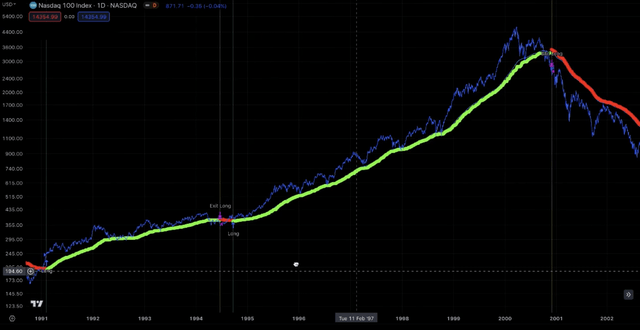

It is also remarkable that investors, operating in a state of deep information asymmetry, started to buy up the tech-heavy Nasdaq shortly after Tim Berners-Lee invention of the world wide web in 1989.

Nasdaq 100 1980s and 1990s (www.ZommaEngine.com)

After a bull market in the 1990s, this led to a blow off top in 2000, as ripe valuations outpaced the promise of the technology. However, an obituary of the age might fairly point out that the far-reaching societal effects of the technology were even greater than its most ardent supporters might have imagined.

Nasdaq 100 market top (www.ZommaEngine.com)

The crash from a frenzied stampede of buying is the flip side, as the herd runs for the exits.

Nasdaq 100 selling frenzy (www.ZommaEngine.com)

Indeed, the crash is even worse than the indices suggest. Many dot com companies went out of business, never to be heard from again. The index constituents changed. There is profound survivorship bias. Picking winners from the rubble like Amazon is always easier in hindsight than during the fog of war.

Beware of the herding effect. The interplay of societal narratives, central bank policy, and technological change exaggerate the natural herding response to information asymmetry.

We must recognize and mathematically model the herding effect as investors stampede in and out of indices in manias or panics if we wish to rationally respond to it.

I will take the argument for the centrality of understanding the herding effect in order to make accurate market predictions to its natural conclusion.

1. Financial Economics should cast aside normative models which falsely claim to be descriptive. If a model claims to have descriptive power, but is not predictive of the future, then it is, ipso facto, not truly descriptive.

2. Animal Spirits, far from being a deviation from the ideal of the rational economic actor, drive the economy, as Robert Schiller and George Akerloff argue in Animal Spirits. Merely describing the issue is insufficient. We must find a solution to the problem of prediction.

3. Academia, and especially the natural sciences, is necessarily materialist in its aims and reductionist in its processes.

However, science departments have a curiously schizophrenic stance towards homo sapiens. On one hand, Biologists are steadfast that humans are animals, evolved like any other species from more primitive antecedents.

However, these same Biologists rarely subject human behavior to the same rigorous observation and measurement that other animals are subjected to in Zoology. Indeed, studying herds of Zebra or Wildebeest in Africa is considered perfectly pedestrian. Yet oddly, the behavior of herds of investors is studied in a completely different academic department called Economics.

And this department called Economics fashions itself a social science, while pursuing empirically unsound normative models which are anything but scientific and would be laughed at by Zoologists who have the inconvenient scientific requirement that hypotheses must be rigorously tested against repeatable observations (and conform to them if the hypotheses are not to be brusquely discarded).

Meanwhile, Zoologists claim that humans are animals, yet refuse to study human behavior with the rigor that they seem to save only for lower animals.

When one has the temerity to question this schizophrenic academic response to the study of homo sapiens, there is much hang wringing and consternation at the impertinence of posing such questions to the academic priesthood, who fall back on tired bromides about the complications introduced by freewill.

They then punt the issue to cognitive neuroscience, and we finally get some incisive progress with behavioral economics luminaries such as Richard Thaler, Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman showing specific, measurable, systematic empirical deviations of human decision making from rationality.

However, plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. We still do not have an empirically sound model for how herds of investors make decisions which has predictive value. The moment we demand coherence of cognitive neuroscience to show how these systematic deviations from rationality can be used to predict the macro behavior of the human herd, we are subjected to more hand-wringing, more platitudes about free will and its relation to other economic actors with free will, and more consternation at the impertinence of posing such questions to the academic priesthood. Intellectually entrepreneurial academics will attempt to end the conversation by making reference to game theory, complexity economics, chaos theory, and cybernetics, but these responses are always notable for their curious absence of any specific quantifiable theory which makes scientifically testable predictions about the future, absent simplistic discussions of the Prisoner's Dilemma.

So we are back to Zoologists and Wildebeest and Zebra. To make any progress, we must be very impolitic and insist that the study of human herds is studied in the only academic department which takes the study of animal herding behavior seriously--Zoology. And we must make the incredibly rude request that Biologists start to mean what they say. If Biologists insist that humans are merely another species of animal, the study of human herding behavior belongs back in the Biology department. There is nothing magical about waving one's hands and saying the words "free will" whenever someone feels too lazy to create an empirical model of a sufficient quality to secure tenure.

4. Therefore, the natural conclusion of my argument is that Economists are making a category error when they attempt to explain the behavior of financial markets using economic models.

According to Wikipedia:

A category mistake, or category error, or categorical mistake, or mistake of category, is a semantic or ontological error in which things belonging to a particular category are presented as if they belong to a different category, or, alternatively, a property is ascribed to a thing that could not possibly have that property.

Unlike the academic priesthood, I am completely serious when I say that the study of human herding behavior belongs in the Biology department rather than in the Economics department.

Biologists admit that animals live in various environments. There is no magical reason why Wildebeests in Africa are worthy of the most rigorous scientific study in their herding behavior, but humans sitting on a trading floor are not.

To those who might smugly claim that office buildings are an artificial environment, whereas the Serengeti of Tanzania is "natural," do they make the same claim of beavers, who go to great lengths to modify the natural environment, and even the course of rivers and streams, with their dams?

The more primitive wooden construction of dams makes it no less artificial than the more complex glass and steel of downtown canyons.

Tired platitudes about the irreducible complexity wrought by rationalistic freewill crumble under the weight of their own illogic, as do ad hoc hypotheses from the other extreme about the impossibility of predicting irrational humans.

Behavior need not be rational to be predictable. It only needs to repeat. Zoologists have recognized the wisdom of this adage for centuries. No biologist would ever argue that the behavior of a gorilla has to be rational to be predictable. If another gorilla pounds its chest, almost all adult male gorillas will attack. Rationality is irrelevant to prediction.

The book Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely eloquently made this case in an elegant examination of cognitive neuroscience. But notably, academia is still unable to bridge the empirical divide of using micro insights into individual human decision-making to create accurate macro models of herding in financial markets. The book described the issue beautifully, but none of the Nobel laureates examined in the book had a solution.

So this problem of how to empirically predict the macro behavior of the human herd--to predict the future of the financial markets--is still elusive.

If we truly understand how individuals make decisions, we must be able to understand how groups of individuals make decisions. After all, the image on a screen the countless pixels that make up of the whole. Yet understanding how the pixels add up to the whole still defies explanation.

Academics believe that this issue is so complex, that it almost rivals the mysticism associated with any supposedly scientific discussions of consciousness, which inevitably devolve into philosophy and pet theories.

And like the problem of using micro observations to explain the workings of the whole--like the relationship of pixels on a screen to the meaning of an image--we can now image individual neurons and groups of neurons with the most advanced technology, but still a coherent explanation of consciousness eludes us.

5. If Economists are making a terrible category error when they attempt to explain the behavior of financial markets using economic models, what is the solution? I would argue that we must be ruthlessly reductionist to get anywhere on the prediction front. That requires a model that most closely resembles a branch limited decision tree and brutally simplistic postulates. If we agree that good science is invariably materialist in its aims and reductionist in its processes, we must take Biology's notion that humans are simply more advanced animals more seriously than Biologists do if we are to make any progress.

Here are some postulates and a conclusion:

a. Humans do not make decisions about the direction of financial market indices with their frontal cortex. In humans and animals, these decisions come from the more primitive pleasure and reward center of the brain, the mesolimbic system--hence herding.

b. Therefore, economic theories are window dressing--a mere fig leaf with the faux arrogance of sophistication to explain embarrassingly primitive processes.

c. The only field of psychology to successfully predict both human and animal behavior is behavioralism.

d. Rewards (such as food) and punishment (such as aversive experiences) shape both human and animal behavior, as behavioralists have proven.

e. Money serves as both punishment and reward for humans (increasing or decreasing the amount under a human's control can serve as a reward and/or punishment).

f. As the famous B.F. Skinner observed, humans do more of what feels good and less of what feels bad.

g. Therefore, studying thresholds of punishment and rewards can bridge the illusory gap between individual and group behavior.

h. In humans and animals, certain thresholds of reward and/or punishment are needed to induce changes in behavior. This explains sideways markets.

i. Exogenous events, like a sheep dog nipping at the heels of a sheep are only the seemingly causal reasons for herding behavior. Relatively few sheep need to have their heels nipped by a dog in order for the herd to change direction. After a certain threshold of sheep move in response to the exogenous event (dogs nipping at their heels), the great mass of the herd moves, because of the primitive structure of the sheep brain. Similarly, once a threshold of relatively few humans in relation to the size of the group start to buy and/or to sell, their actions, once certain thresholds are reached, induce market participants, as a herd, like sheep, to move as they are punished or rewarded by the increase and/or decrease in the values of their portfolios. Like sheep, once certain thresholds of punishment and/or reward are breached, these moves become self-reinforcing through the herding effect, as people do more of what feels good (what they are rewarded for) and less of what feels bad (what they are punished for).

j. In conclusion, this accounts for the outperformance of trend following techniques which take mathematical advantage of the herding effect. Simple behavioral causes of reward and punishment can only be described robustly by simple models (remember, ruthless reductionism and Occam's razor). Two Sigma has convincingly proven in their exhaustive factor analysis that trend following techniques are one of the more robust factors.

k. This also proves why dividend investors can potentially enjoy outsized returns if they pick their investments wisely. Their investment return often does not come primarily from the price movements of their investments. Therefore, the pleasure and the pain reward system is primarily supplied by dividends and/or interest. Therefore, they can be rewarded if they invest in robust companies that pay them to reap the long term rewards of income investing, including growing dividends. Growing dividends allow these investors to ignore the pleasure and the pain associated with market gyrations, because they are outweighed by the pleasure of their investment income.

In conclusion, we are almost all investing incorrectly. For investors with fixed amounts of capital, either focus on long term trend following techniques, or on income investing. Ignore complex economic commentaries. They are a fig leaf for the embarrassing simplicity of the herding effect and of income investing.

This article was written by

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Hypothetical performance results have many inherent limitations, some of which are described below. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown; in fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual results subsequently achieved by any particular trading program. One of the limitations of hypothetical performance results is that they are generally prepared with the benefit of hindsight. In addition, hypothetical trading does not involve financial risk, and no hypothetical trading record can completely account for the impact of financial risk of actual trading. For example, the ability to withstand losses or to adhere to a particular trading program in spite of trading losses are material points which can also adversely affect actual trading results. There are numerous other factors related to the markets in general or to the implementation of any specific trading program which cannot be fully accounted for in the preparation of hypothetical performance results and all which can adversely affect

Seeking Alpha's Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.