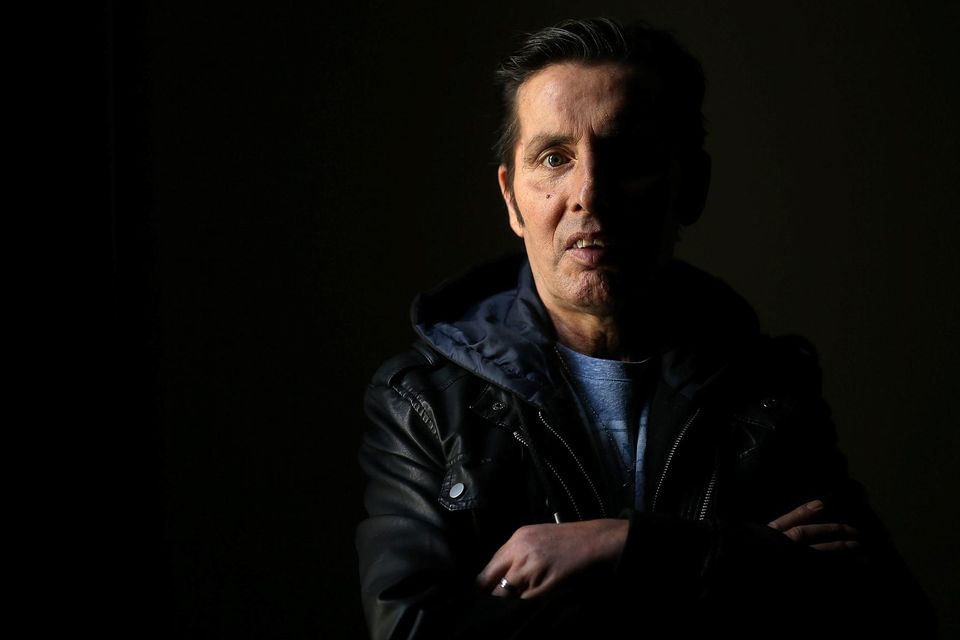

Ed Power: Christy Dignam was a fighter, romantic and street poet whose legacy in Irish rock is secure

There will forever be a hallowed place in the pantheon of Irish rock for Christy Dignam.

The singer, who has died aged 63, did not enjoy the global success of Bono and U2.

Nor was he as iconic as Phil Lynott. But he was a fighter, a romantic and a street poet who carved out a near-40-year career as frontman of Aslan, his charisma and doggedness the twin engines that drove the band ever onwards.

Aslan’s two biggest hits, This Is and Crazy World provided a window into the soul of Dignam, who was born at Holles Street Hospital, Dublin, in May 1960.

Dignam was a troubled artist, his husky voice brimming with both sweetness and darkness and infused with the traumas of childhood abuse and an adulthood bedevilled with addiction.

He was also a dreamer who believed in the healing power of music.

That crackle of optimism is the animating factor that runs through the best of Aslan’s music.

Only Dignam could have delivered a seemingly schmalzy line such as “Yeah you stop, you look/You're searching for the meaning” – from the chorus to 1988’s This Is – and imbue it with such sad wisdom.

His legacy is complicated because Aslan never broke through internationally.

Christy Dignam, centre, with his Aslan bandmates, from left, Billy McGuinness, Tony McGuinness, Alan Downey and Joe Jewell in 2000. Photo: Tony Gavin

They were on the brink of doing so in the late 1980s when Dignam’s addiction to heroin got out of hand.

The breaking point for the rest of the group was when he was detained in a raid on a dealer by the Garda drug squad (in an investigation led by future Garda Commissioner Nóirín O’Sullivan).

The rest of Aslan drummed him out. They lost their record deal, having briefly tried to replace him with Eamon Doyle. All the momentum created by This Is and their accompanying album Feel No Shame – both reached number one here – turned to dust.

But Dignam defied the notion that there are no second acts in Irish music.

He toured America as one half of the acoustic duo Dignam and Goff, while British prog rock band Marillion tried to recruit him as their singer (he turned them down on the basis that their music was baggy and indulgent and that the musicians were all far older than him).

Then, in 1993, Aslan embarked on one of Irish rock’s great comebacks when they reformed for a charity gig – only they found that the old chemistry endured.

They wrote Crazy World, their great anthem, during the two weeks they had to rehearse for that fundraiser in Finglas.

It went to number one in Ireland, though Dignam was annoyed that BMG Records declined to release it in the UK, feeling it wasn’t a potential hit (it connected with the anti-Irishness that he felt rippled through the British music industry).

Crazy World never went further than Ireland.

Still, it didn’t matter. Aslan were Ireland’s band, as confirmed when they filled the Point Depot – as the 3Arena was then – on St Stephen’s Night, 1999.

Yet regardless of the size of the venue – and Dignam never had an issue playing smaller pubs and clubs – they never stop working, or believing their music could make a difference. Rather than global hits or millions in the bank, that is Dignam’s legacy.

Even before his 2013 diagnosis with cancer caused by amyloidosis – a rare condition involving the build-up of abnormal proteins – Dignam had encountered his share of heartache and tragedy.

ARCHIVE: Christy Dignam talks about going through chemotherapy during Covid-19 on The Great Big Irish Thank You

His mother had suffered an emotionally abusive childhood at the hands of her grandmother and her mother had walked out on the family when she was 14.

His father was abused at Artane Industrial School and would seek redress from the state commission investigating the maltreatment of children at such institutions.

Dignam was the second of eight children and grew up in Finglas, where he attended Naomh Feargal primary school and Patrician College, run by the Christian Brothers.

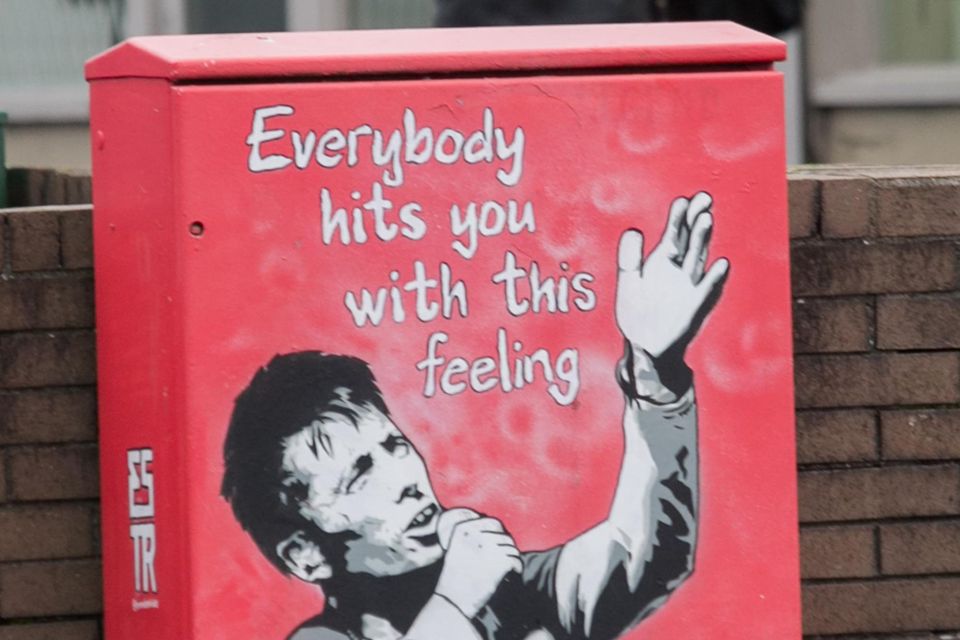

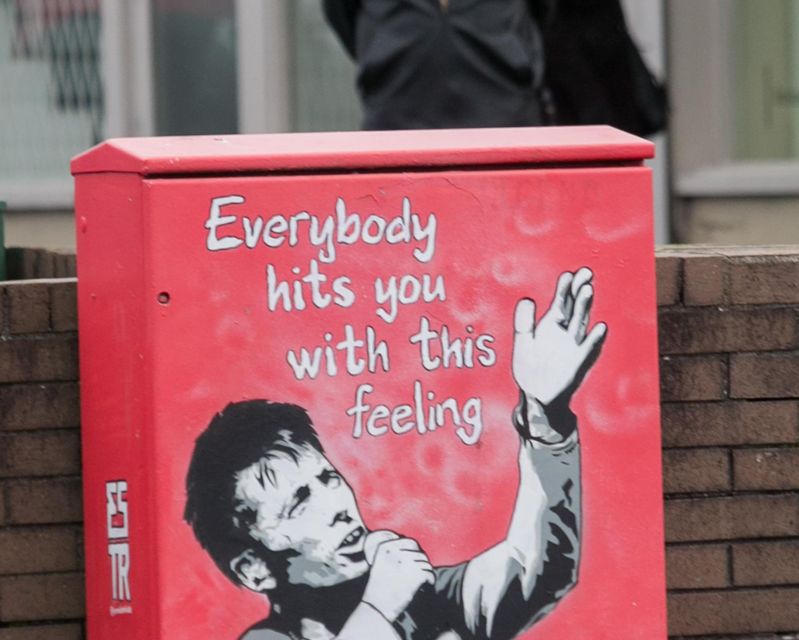

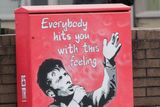

A mural of Christy Dignam in Finglas on Dublin's northside. Photo: Gareth Chaney/Collins

Aged six, he was abused repeatedly by a neighbour. He suppressed the memories for years – but when he went into rehab for the first time for heroin, it all came rushing back. Drugs, he realised, were his way of medicating the unresolved trauma.

He first tried heroin aged 19. In his 2019 memoir, My Crazy World, he recalls the effect of the drug as unlike anything he has experienced before. There was no high – instead, it made him feel complete, filling a void in his soul.

Addiction remained an on-off issue through his early years in music and his marriage in the early 1980s to his wife Kathryn, with whom he has a daughter Kiera (he was grandfather to Cian, Jake and Ava).

Dignam started as vocalist with a local covers group, Electron, in Finglas while working on the production line at the Player Wills cigarette factory on the South Circular Road and later Irish Continental Ferries and Telecom Éireann, where he installed underground cables.

His first gig as singer was at an IRA fundraiser in 1977, at the Towers pub in Ballymun. He and his bandmates were not aware of the nature of the gig until they stepped on stage.

At the end of the set, they were told that they were expected to sing the national anthem. Not knowing the words, they instead “did a runner”.

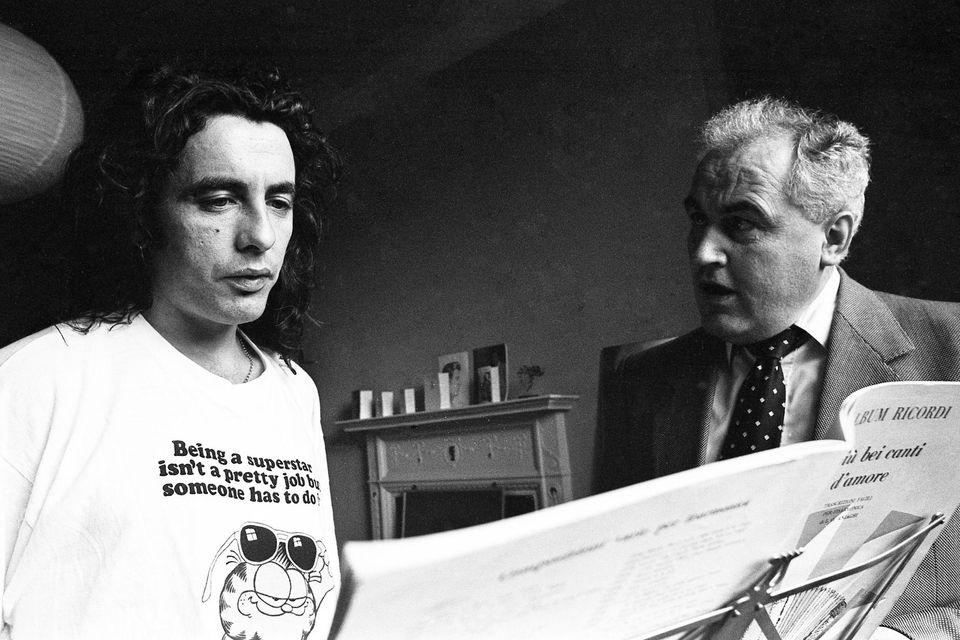

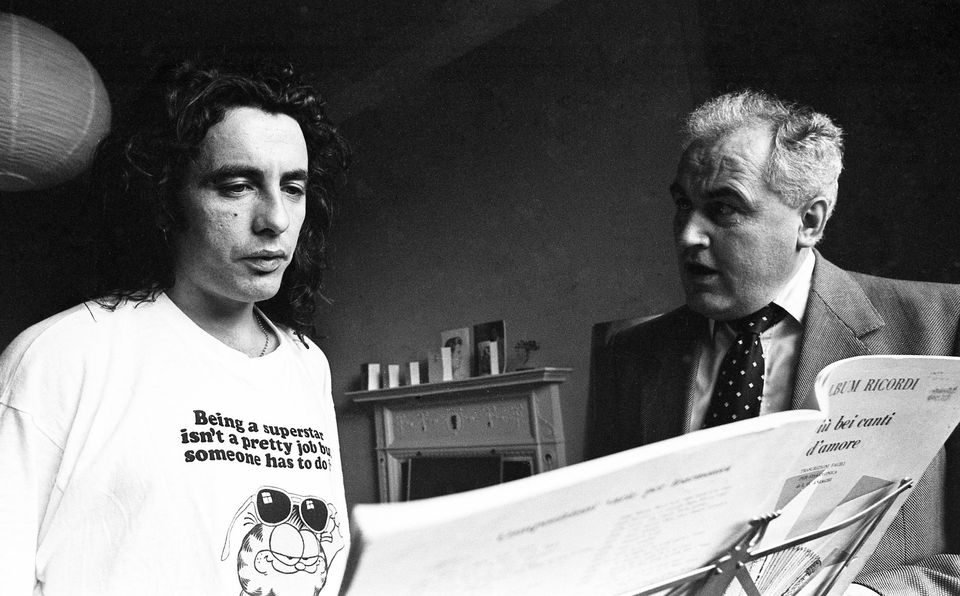

Dignam did not sing in public for the next year. Later, he studied the bel canto singing technique at the Parnell School of Music with Frank Merriman, who also tutored Sinéad O’Connor.

Dignam was not a natural showman in those early years. Under the spotlight, he would be stricken with nerves.

His method of coping was to close his eyes and pretend he was somewhere else. But singing “blind” left him at risk of tripping over the wires and speakers.

Christy Dignam getting music lessons from Frank Merriman at the Parnell School of Music in 1989. Photo: Independent Newspapers Ireland/NLI Collection

This led to an early signature of early Aslan performances: Dignam crooning shoeless with his eye shut (he was better at negotiating the tangle of wires in bare feet).

Aslan would emerge from the ashes of his next band, the post-punk outfit Meelah XVIII. They had decided to change their name after they noticed that most up-and-coming groups– Cactus World News, Flock Of Seagulls and others – had long, complicated monikers.

Aslan was simple – inspired by CS Lewis and by the fact that it contained five letters, one for each member of the project.

They had the good fortune to come along as Dublin had become suddenly and surreally zeitgeisty. U2 had put the city on the radar – and international artists such as Spandau Ballet were moving here to take advantage of the artists’ tax exemption.

Pubs such as the Pink Elephant on South Frederick Street became a hang-out for pop stars and wannabes alike. Aslan were soon regulars.

They also came to the attention of U2, who considered signing Dignam and the gang to their vanity label, Mother Records.

But a meeting with Bono at the Dockers Pub around the corner from Windmill Lane studio did not go as planned.

In his memoir, Dignam recalls the U2 singer turning up two hours later and then, over a sausage sandwich, telling Dignam that he didn’t rate their favourite song, This Is.

He did offer to lend them U2’s eight-track recorder – his polite way of telling Aslan that they wouldn’t be signing to Mother.

U2 and Aslan would later become close. Bono and the Edge covered This Is by video link at a 2013 tribute concert for Dignam. And when Dignam was taking time off to deal with his illness, Bono called to his house, where they discussed life, death and songwriting.

Aslan never stop working, or believing their music could make a difference. Rather than global hits or millions in the bank, that is Christy Dignam’s legacy

Dignam was always ambitious. On hearing that Depeche Mode were playing Dublin, he and Meelah XVIII bassist Mick McKenna travelled to Basildon in Essex, Depeche Mode’s home town.

The plan was to track down the band and request a support slot. To their surprise, Depeche Mode were not to be found standing on a street corner in suburban Essex.

However, on the train back to London they saw the group’s keyboardist Andy Fletcher. Dignam approached only to be shooed away – Fletcher told him to contact the promoter and that the question of opening bands had nothing to do with him.

Aslan were not dissuaded by such indifference. Nor did Bono’s lack of interest put them off.

Initially rejected by CBS Records, they later signed to EMI. This was a thrill for Dignam as EMI was the label of his hero, David Bowie.

And when Bowie was announced as Slane headliner in 1987, Aslan told their management that they had to book the gig.

Their manager came through and they opened for Bowie that summer. Dignam’s performance was watched by Bowie’s guitarist Carlos Alomar from side of stage.

Christy Dignam with his wife Kathryn at the An Post Irish book awards at the Convention Centre in Dublin in 2019. Photo: Mark Condren

However, Bowie – still shaken by the killing of John Lennon seven years earlier – was paranoid about his safety and kept his distance. He retired to the Pink Elephant after the gig, but his security turned away Aslan guitarist Billy McGuinness who went up to request an autograph.

Years later, Bowie would apologise to Dignam, explaining he had been neurotic about his safety – especially in Ireland, at the height of IRA violence.

The success of This Is in Ireland led to EMI taking a punt on Aslan in the United States. They paid $60,000 to “buy” the band onto the US tour of Graham Parker.

The gigs were positively received. However, it was the partying that Dignam remembered.

Cocaine was everywhere and while his bandmates were happy to go back to their normal – and clean – lives afterwards, Dignam’s addictive personality prevented him from doing so.

Back home, his heroin intake increased. Soon his habit was out of control. At a record signing in Waterford, he told the band he had a cold and could not continue.

A quick call to his dealer in Dublin remedied the situation and suddenly he was full of life and eager to sign anything in sight.

Throughout his addiction, Dignam believed he was pulling the wool over the eyes of his family and bandmates.

Christy Dignam salutes the crowd at 'A Night For Christy’ at the Olympia Theatre in 2013. Photo: Kobpix

Still, it was obvious to everyone that he was spiralling. And after his arrest, the rest of Aslan finally concluded they had no alternative but to show him the door.

Dignam sought treatment at the Rutland Centre.

There, he was encouraged to confront dark episodes from his past – which is how he at last dealt with the buried memory of childhood abuse.

Yet, even as Aslan became Ireland’s favourite band, Dignam’s battle with addiction dragged on. He turned a corner at the Buddhist monastery Wat Tham Krabok in Thailand in 2004 (he continued to use on returning to Ireland but discovered all the thrill had gone out of drugs).

Later, a course of methadone treatment helped Dignam quit heroin for good. And through it all, Aslan never stopped performing. In 2021, he poured his lockdown blues into a well-received solo LP, The Man Who Stayed Alive, which debuted at seven in the charts.

Years later, he would recall how in his 20s he and Kathryn had considered moving abroad.

“Just before the band took off me and the wife went to Australia for a holiday. I loved it out there,” he said. “We decided we would give Aslan a year and if it didn't work out, we'd move to Australia.”

Yet it did work out – and while there were plenty of bumps in the road, Aslan would become a fixture in Irish rock.

They never conquered the world. But they did conquer Ireland and, in Dignam, they had a frontman whose legacy will live on for as along as people are singing Crazy World. And that may well be forever.