There is a ballet class that takes place in the East Village of New York most Mondays at 10:45 a.m. It has all the markings of a makeshift studio: an abandoned stage, portable barres, two small mirrors wheeled into place. Dancers, polite, mostly quiet at first, shift their spines from side-to-side, pressing palms into sore calves. The presence of gnarled toes is comforting to those who contort their bodies for a living: feet only a dancer could love.

This ballet studio is unremarkable, as many are—dancers have learned to create magic in whatever space they can get their hands on. It’s the community I’ve come to see. Today’s students are outfitted in striped leg warmers littered with holes, leotards the color of a neon highlighter, long black skirts, and dangling cherry earrings. At the start of class, each dancer announces their name and their pronouns. Most who seek out this class do so for the same reason: It was designed as a friendly space for queer cis women, trans, and nonbinary dancers. In ballet—an industry built on intrinsically problematic gender roles—this is a beautiful occurrence.

“We’re skipping fourth position,” Adriana Pierce, founder of Queer the Ballet, says to her students, who giggle in return. Pierce has no interest in recreating a class environment she finds irrevocably broken, nor an art form that has historically barred queer dancers and dancers of color from its ranks. “Fuck fourth.”

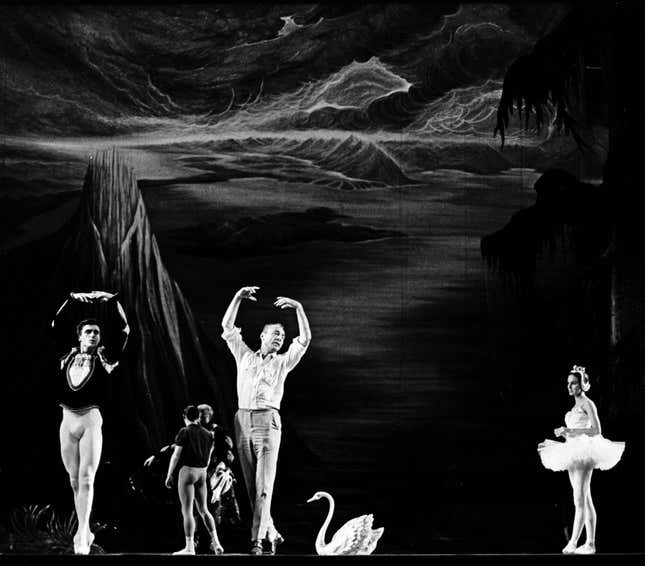

That environment, the one Pierce hopes to counteract, was cultivated by George Balanchine. Widely considered the father of American ballet, the famed choreographer and founder of New York City Ballet (NYCB, the country’s most recognized ballet company) has been dead 40 years. But his legacy, like his watchful eye, lingers in most suburban studios and metropolitan practice rooms. His classic ballets—Apollo, Prodigal Son, Serenade—can still be seen on stages all over the world, danced by artists born decades after his passing. The memory of Balanchine lives in their bones, animating their limbs and appraising their bodies, as ballet’s oldest and most renowned institutions ceaselessly defend his legacy.

The culture of ballet, much like the notion of Balanchine as a man above reproach, has long been under scrutiny from outsiders. But over the last several years, an increasing number of former and current dancers have come forward with their own searing accounts of the ballet world. They include a memoir from Alice Robb, a former student of School of American Ballet (SAB, the feeder school into NYCB). A scorching tell-all from NYCB soloist Georgina Pazcoguin, who last month announced her retirement to focus on AAPI-centering art. A biting analysis of the profession’s shortcomings by dancer-turned-journalist Chloe Angyal. An 817-page biography that reconciles Balanchine the god with Balanchine the mortal. They’ve given new urgency to the reckoning within the industry that started with MeToo.

The podcast The Turning: Room of Mirrors, whose new season premiered earlier this year, takes that reckoning even further. Over the course of ten episodes, host and co-producer Erika Lantz thoughtfully weaves together the voices of a dozen or so dancers across generations, including those of a “dying breed” who worked with Balanchine. Together, they attempt to make sense of ballet’s contemporary draw, discussing the tension between what is seen—grace, flight, weightlessness—and what is felt—pain, gravity. By podcast’s end, the space between the ballet dancer, once alien and unknowable, and her onlookers has disappeared, giving a close-up view of the industry’s own warped mythology.

Like many flailing to situate ballet in a feminist future, Lantz wonders, “How far do you go for the sake of something you believe in?”

When perfection isn’t enough

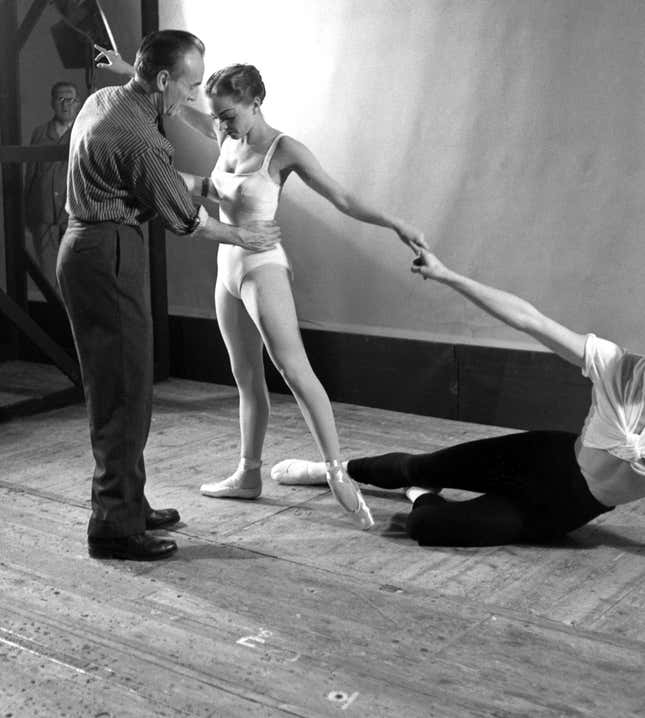

Depending on which circle of dancers you ask, there are two Balanchines—and by proxy, two visions of ballet—that exist in the field’s memory. There is Balanchine the choreographic genius, the mentor, the gentleman who conducted his inner monologues not in words, but in ballet steps. That Balanchine required total devotion of his dancers, and they were happy to oblige.

“I was very surprised at how much religious language is used around Balanchine,” Lantz tells Jezebel in a phone interview. “But it resonated with me, because when I used to dance, or when I hear music, or I’m involved in music or experience art, it takes me to what feels like a higher plane. It feels religious. It’s elevating, somehow.”

Those who insist ballet is already feminist often cite Balanchine’s famous words: “Ballet is woman.” Lantz recounts how one of Balanchine’s favorite muses Suzanne Farrell wrote in her memoir, “Balanchine was a feminist long before it was the fashion…[and] devoted his life to celebrating female independence.” And as the New York Times puts it, “The feminist case for ballet is right there onstage: It’s freedom. In his choreography, Balanchine made a space for women in particular—and for each woman—to be free.”

But then there is another Balanchine, more ghost than a god. In his muses, Balanchine often looked for dancers not yet matured, so “he could shape them, he could form them,” former NYCB principal Stephanie Saland recalls in The Turning. He dated many of them, lopsided power dynamics be damned. He became upset if they had children or got married, forcing some to date and marry in secret. Former muse Holly Howard reportedly had four abortions by Balanchine. Questions still remain over whether the abortions, and the sexual relationship itself, were consensual. “I am your mother,” Balanchine told his dancers, former dancer Wilhelmina Frankfurt says. “I am a mother.”

Though Balanchine is long gone, his obsession with the feminine body—as an instrument he could manipulate, a doll he could bring to life—continues to shape the ideal modern ballerina. Many of today’s stars are still rail thin and white, just as Balanchine would’ve preferred them. Though we can hold him partly responsible, artistic directors (70% of those employed by the largest 50 companies are men), ballet masters, and donors have all played their part in resisting change. And while real power still evades the dancers, to represent them as powerless would also be a distortion of the truth.

“In discussing the power that Balanchine had, the danger is that you can go too far in either direction, where you start to strip some of the dancers of the agency they had, as well,” Lantz says. “I think that’s important to remember—how they were artists, and they did have agency, and they did feel powerful often when they danced. It’s complicated.”

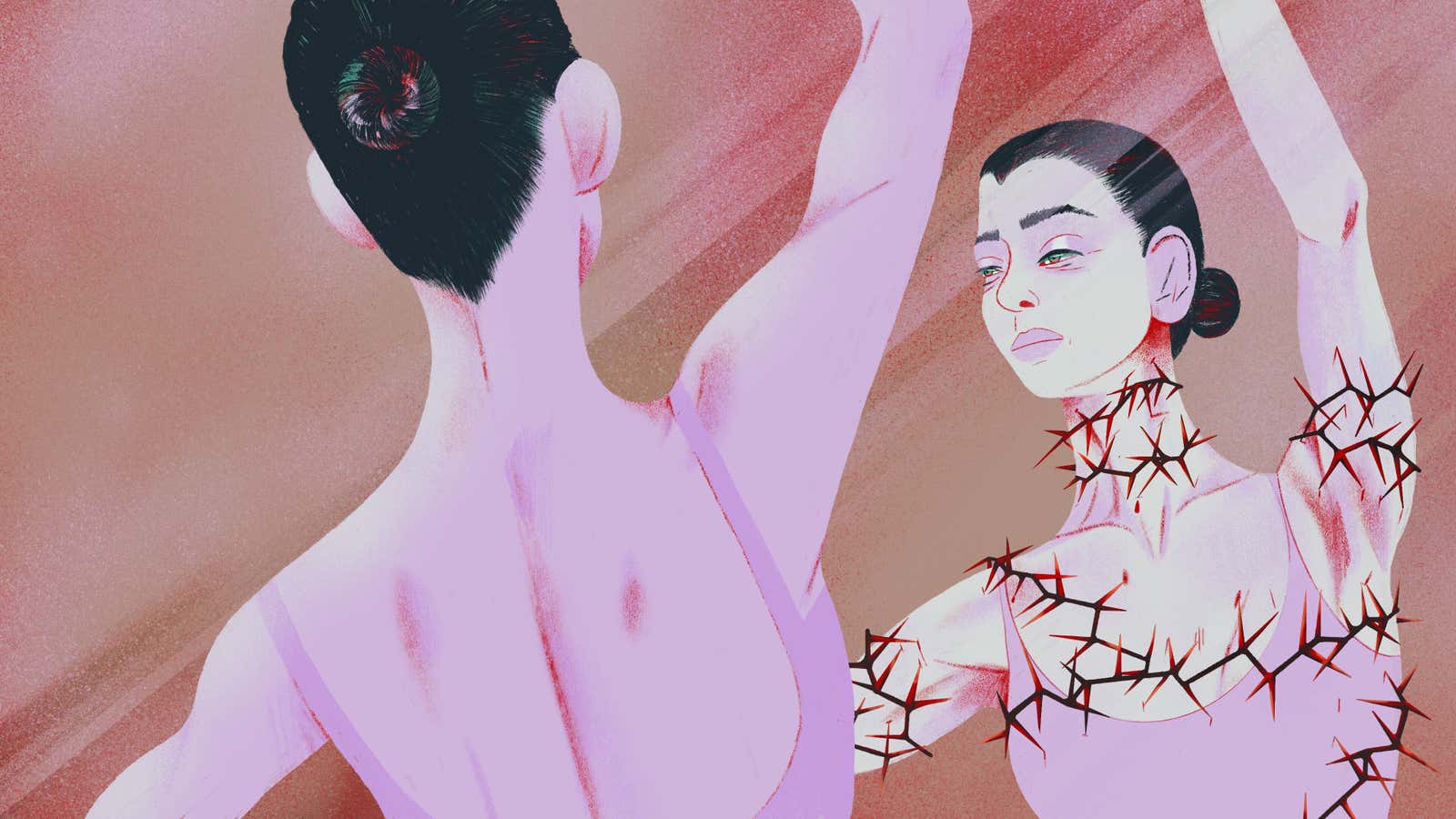

Anyone who has danced in a mirrored room or upon a lit stage will tell you that ballet feels like freedom. When I need God—what I imagine needing God feels like—I send my thoughts to the stage, where music cradles my body, buoys it, rocks me into a fit of ecstasy. It feels like control, like intoxication. But, while no one person can decide what is or isn’t empowering in a body—that’s a singular experience—to dance the part of a free woman isn’t necessarily to become her. If the steps were drawn up by someone who does not look like you, who does not care what happens to your body, is that freedom, or are you just another swan instructed to flap her wings onstage?

And what happens upon exiting stage left? Where does that freedom go then?

At present, there are so few blisteringly honest accounts from modern retirees that it may be decades before we have a clear picture of the mental and emotional toll of contemporary ballet on its artists. Former NYCB corps member Sophie Charles (née Flack), however, is one of the handful of former dancers openly talking about it.

“We were systematically lied to since childhood that the skills that we acquired in the ballet world would serve us in our next endeavor, and for me, it was the opposite,” says Charles, now a writer and mother of two whose voice was featured on The Turning. “I tried applying what worked for me in the ballet world to being a mother for the first time, and it was completely catastrophic. My perfectionism, my determination, my hard work, my self-sacrifice…all the things that make a great dancer completely wrecked me mentally and physically as a mother.”

Charles has dealt with anxiety and depression her whole life, but her anxiety became untenable while trying to keep up with NYCB’s rigorous pace with a learning disorder: an auditory processing issue that meant she couldn’t pick up choreography as quickly as everyone else. To get her up to speed, ballet mistresses often drilled Charles in front of a room packed with her peers, or kept her after class to run combinations “again and again and again and again.” She was humiliated. For her own protection, she learned to shut those feelings down—a mechanism that, years later, would nearly cost her her life.

“It becomes necessary in ballet to hide your inner life so your outside can seem serene. I was able to do that for the first seven months of new motherhood while I was miserable and suffering on the inside: I didn’t ask for help and just continued pushing myself to the brink,” Charles says. “The internal monologue during ballet was often, ‘Well, I survived this, I made it through’...literally life or death talk. And that’s the level that I would push myself oftentimes with postpartum depression. I almost didn’t make it. I almost didn’t survive.”

In ballet, and in Balanchine’s world, the body is inextricable from the criticisms of the work itself. Aesthetic preferences, as Turning Pointe author Angyal references in the podcast, are cloaked in unassuming language. Balanchine’s preference for white bodies, thoughtless carbon copies, became “symmetry” onstage. Glorified thinness became “the line” (an onlooker should be able to trace the distance between the tip of the toe and the crown of the head without unwanted curves or distractions). Perhaps Balanchine centered the woman on his stage, gave her freedom in choreography. But within her own body, captivity.

As Lantz notes, “I think there’s a sense in his work that the ballerina, the woman who for a certain moment is ideal, is never fully attainable. Or perhaps, once she appears to be attained, he loses interest. He moves onto something else… She’s no longer ideal.”

The irony is this: In order to reach the top ranks of the field, a dancer must both possess intimate knowledge of her instrument, and divorce herself from her body to tolerate the emotional and physical turmoil wrought by ballet. It’s also no coincidence that a renewed fascination with ballerinas is happening at the same time as Ozempic weight loss culture and the rebranding of “sickness” as beauty—concerning trends that take place at that intersection of body-consciousness and dissociation. “The concept of beauty that you’re striving for as part of the art form, of course, comes from and also affects cultural standards of beauty,” Lantz tells Jezebel.

Throughout her time at SAB and NYCB, Charles says she dealt with severe anorexia. Though her instructors initially expressed their concern about her weight loss, two years later she received her first of several “fat talks.” A teacher pulled her aside to tell her that Peter Martins, the beleaguered former director of the company who was hand-selected by Balanchine as his successor, wanted her to lose weight. “For me, being told to lose weight was small potatoes… Until I heard the [Turning episode she was featured in], I didn’t even realize that that was as messed up as it was,” she says. After all, she says she had gotten the most praise from Martins when her eating disorder was at its worst. “They don’t give a shit about what’s happening on the inside, just what’s happening on the outside.” (NYCB and SAB did respond to a request for comment.)

Kathryn Morgan, another prominent voice in The Turning, also looks back on her ballet career with conflicted feelings. Morgan was considered a rising star as an 18-year-old NYCB dancer, until she was diagnosed with a thyroid disease called Hashimoto’s. In 2012, she decided to take time away from ballet to give her body space to heal—a stretch that turned into seven years. Only with distance did she come to see that the ballet culture she’d grown up in, which had demanded thinness, pliability, and perfection, had been steeped in toxicity.

While at NYCB, Morgan vividly remembers learning the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy in Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, she tells Jezebel. During rehearsal, the ballet master instructed her to come to the center of the stage, noting that “all the kids” would circle around her in the second act.

“I remember thinking, ‘Wait, she’s talking about the corps de ballet. And she’s calling them kids. Most of them are older than me,’” Morgan says.

The infantilization of professionals played out on the dancers’ bodies, too. Pre-pubescent was the most sought-after look in mirrored ballet studios. Markers of womanhood—large breasts, hips, or bellies—were discouraged. Body types that skewed from the sinewy ideal with its protruding bones were dealt with as a question of morality or a lack of work ethic. “I think there’s always that voice, being a dancer, which is drilled into you,” Morgan says. “You could have worked harder, you could have eaten less, you could have done more.”

Much to her surprise, in 2019, Miami City Ballet invited Morgan to audition for their company. She was promised a healthier work environment and was hired back as a soloist. After nearly a decade away from ballet, she was hopeful that the field had changed for the better. Less than a year later, she quit. She recorded a YouTube video, titled “Mental Health and Body Image,” explaining why.

“I knew I could get blacklisted for speaking out,” Morgan says. People in the ballet realm either stopped talking to her or distanced themselves from her in the video’s aftermath, though she says some Miami colleagues privately expressed that they agreed with her stance. “I don’t take it personally. They have to keep their jobs. I lived that, I know what that’s like. It’s safer to stay silent.”

For Morgan, the only real sense of agency she experienced within ballet was the moment she realized she could leave professional companies for good: Her YouTube channel, where she teaches ballet optimized for longevity, began performing well enough that she could rely on it financially, and the videos allowed for more independence than the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy ever could. Still, after everything, she can’t quit ballet. It remains the spinning center of her life.

“I still love it. It’s all I ever wanted to do. It’s why I am still dancing,” Morgan tells Jezebel. “Because this is way too hard and way too painful to keep doing if you don’t love it.”

Dancers reimagine an art form

Much like modern womanhood and motherhood, ballet dancers who studied in the Balanchine method “were trained to make impossible things look easy,” says Lantz. The act of a ballet dancer gliding across the stage like a skater upon water is meant to puzzle audiences—an optical illusion, as if she has ascended her physical form to something lighter, more heavenly.

The art is visually beautiful to the beholder, of course, but that’s only half the point: Women aren’t supposed to be able to turn on their toes without suffering. They aren’t supposed to return to the stage night after night, with cracked calluses and mangled feet. But they do, and do, and do. This is, in part, why we go to the ballet. Because it should not be possible. Because for an hour or two or three, we allow ourselves to believe that this breathtaking work has no consequences, that the pain isn’t real. Or, a more compelling theory: The pain is excruciating, and she’s tucked it away somewhere unseen.

“Part of [this fixation] is our human fascination with gore,” Lantz says. “You want to know what it’s like when someone takes their body to an extreme in a way you might be scared to do yourself. But there’s a weirdness to it: Why does the fact that we know that dancing is painful make it more compelling for a lot of audiences? They want to know if dancers have bloody toes, lose their toenails, if their feet are gross. This whole intersection of beauty and pain and the idea that they should be linked is problematic.”

Like any sport, a healthy amount of pain is to be expected in ballet. And those who have ascended to principal spots in top companies deserve every ounce of admiration an audience can give them. What they’ve achieved with their limbs, their ability to explode onto a stage, is their doing alone. But their brilliance cannot cast a shadow over those who fell in love with ballet only to find it had destroyed or excluded them by design.

Whether ballet can survive in its current form remains to be seen, but asking audiences to better inform themselves of the industry’s realities is a good place to start. As Angyal has repeatedly reminded ballet-goers, pre-professional and professional ballet dancers are not only devotees of the arts but workers. And that means their right to mental health, safety, and protection from body discrimination should come before all else.

“Normally I play classical versions of pop music, but today we’re going full ballet,” Pierce tells her students as she starts up a version of Tchaikovsky’s “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” that sounds as though the pianist did a bump of cocaine before sitting down to play. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me, but we’re going baaaaaallet today.”

Going “full ballet” for Pierce is a complicated choice. Before she founded Queer the Ballet, she’d danced for NYCB, where she came out—somewhat against her will—to the entire corps de ballet in an all-women’s dressing room. She became the only out queer woman in the company that day. Until she left Miami City Ballet in 2017, she never felt her version of femininity was accepted, nor did she want any of her fellow dancers to think she was checking them out. Onstage, she lived in fear that audience members would be able to sniff out the “dyke” in the company, she recounted in The Turning, as if her movements might read too “butch” amongst the dainty swans and fairies.

“I was in the top ballet company, and I thought I was the only one like me,” Pierce tells Jezebel. “It wasn’t until two years ago, when I had a conversation on Zoom with 14 other queer dancers, women from all over the world in ballet, that we started talking about this openly.”

As part of her mission, Pierce set out to choreograph works for professional companies that are explicitly queer. That includes pas de deux (a dance made for two people) between two queer women, which defies the heterosexual romances typified by Balanchine ballets: a male dancer providing stability and support for a woman, his betrothed, on her toes. Romantic pas de deux between two men are no longer impossible to find; Lauren Lovette’s Not Our Fate for NYCB featured one in 2017, as did American Ballet Theatre’s Touché by Christopher Rudd in 2020. But male-identifying dancers are trained early on to lift and partner. Most women never receive that sort of training; they are taught, instead, to be propped up, handled, and caught.

“When you have two women, how do we even start? How do we even touch each other? Forget about doing a lift. We are socialized and trained to not have agency, period,” says Pierce. “I don’t think [partnering queer women] fully fits into the box that we create for women in ballet. It’s really hard for people to envision women having agency, especially over another woman. So we are profoundly questioning gender, and profoundly questioning sexuality, and ballet, and what all of that means.”

From Pierce’s vantage point, there are currently no explicitly queer pas de deuxs between two women being danced by major American ballet companies. (Two Royal Ballet dancers kissed in Wayne McGregor’s 2015 Woolf Works in the UK, and a German company is set to premiere a gay Giselle this year.) She notes that Justin Peck choreographed a pas de deux between two women in NYCB’s 2022 Partita, but she wouldn’t call it outwardly romantic. To his credit, former American Ballet Theatre artistic director Kevin McKenzie acquired one of Pierce’s works in 2021, which the company has only performed internationally on tour. In order to move ballet forward, Pierce says we need our mainstream companies to continue to take those risks by inviting in new voices—to drown out the Balanchine of it all.

“Seeing two women on stage, as Adriana phrased it [in The Turning], ‘being tender towards each other’ struck me so deeply and so emotionally,” says Lantz. “It was one of those many lightbulb moments where you realize what you have and haven’t seen represented on stage and how that affects your concept of gender. And I just think this pas de deux is this little crystallized version of how gender is conceptualized in ballet.”

I don’t know if changing gendered roles onstage is enough to jumpstart an institutional overhaul. But what Pierce shows us—what Juilliard’s Alicia Graf-Mack, and Angela Trimbur, and Ballet Hispánico and Pacific Northwest Ballet, and NYCB’s Gilbert Bolden III all show us—is that it doesn’t have to be this way. Dancers and historians of color are correcting the record to show that much of Balanchine’s sensibilities were adopted from an “Africanist aesthetic,” Lantz reports. Adults who once quit ballet are returning to the barre with renewed silliness. Students of all genders at Juilliard are given the option of learning pointe. And even at its most indefensible, this craft that so many of us young people dedicated our lives to lures us back into the audience. We watch the futures we squandered leap across the stage, wondering if it might be possible for ballet to produce such brilliance with more protections in place…if one might feel something faintly holy in an equitable workplace. We return to those seats because, with every tired ligament and tweaked joint, we love ballet with our entire bodies, and we will wait for it to love us back.

I also know that in an East Village ballet class on a Monday morning, a six-foot-tall dancer who was only ever taught to lift others is being hoisted into the air by someone half their size. You can see the possibilities erupting in their minds as they’re shocked by their own strength, their ability to be an anchor for others. Here is something worth saving—something our bodies can endure for a long, long time to come.