Disney’s Full Monty revival strips away classless illusion

In an era when screen portrayals of working-class British life have waned, the lads of the 1997 classic are returning — and things have hardly got better

It’s easy to be cynical about Disney+ reviving The Fully Monty as an eight-episode miniseries, bringing back most of the original cast and original writer Simon Beaufoy.

It is a cliché to argue that Hollywood has no original ideas. In some ways, film and television are as creative and inventive as they have ever been. However, there is also a sense that mainstream culture is dominated by an endless stream of recycled ideas and concepts, with studios flailing desperately for the guaranteed return on investment that comes from a Spider-Man or Batman film.

Skipping through the television channels over the past decade, it’s even worse: one might assume that the 1990s never ended. The X-Files came back for a two-season revival. Will & Grace enjoyed a three-season resurrection on NBC. And Just Like That returns for a second season this year, catching up with the girls from Sex and the City 25 years after audiences first tuned in. Even Roseanne came back, with ABC later rebranding the series as The Connors.

Part of this trend is driven by the desire to revisit old characters played by their original actors. The Star Wars sequels are the highest-profile recent examples, but the trend even extends to horror, with Jamie Lee Curtis returning to Halloween and Ellen Burstyn coming back to The Exorcist. This month alone, 71-year-old Michael Keaton is returning as the Caped Crusader in The Flash and 80-year-old Harrison Ford is once again taking up the bullwhip in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

In this context, a legacy sequel to The Full Monty feels like a punchline to a grim joke. Has Disney dug so deep into the toy chest of intellectual property that the most viable remaining option is a streaming series about a bunch of sexagenarian steel-workers-turned-strippers?

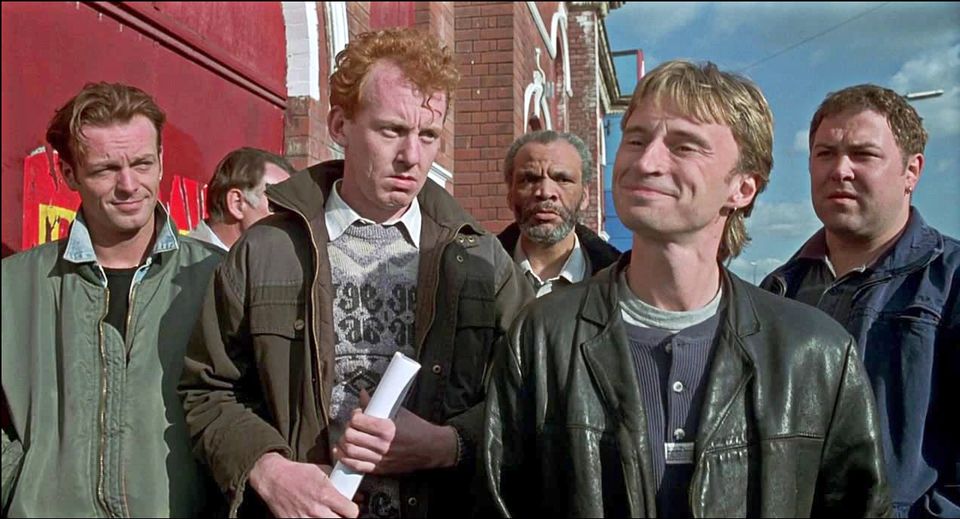

Hugo Speer, Tom Wilkinson, Steve Huison, Paul Barber, Robert Carlyle and Mark Addy in The Full Monty (1997)

Of course, it is easy to lose sight of how successful The Full Monty was. It is inexorably tied to late-1990s Britain. It arrived a few months after Tony Blair’s landslide victory, with the new prime minister even taking the opportunity of his first official trip to Japan to recommend the film to local moviegoers. It came out two days before the death of Princess Diana, and topped the British box office that weekend.

Perhaps more appealingly to Disney, who inherited the rights through their purchase of Fox, it was a global phenomenon. It earned £200m on a £3m budget, including £38m from the US, where it outgrossed other major films from the same year, such as LA Confidential and the Robin Williams and Billy Crystal vehicle Father’s Day. Arriving as part of the same wave of “Cool Britannia” as Trainspotting and the Spice Girls, it even inspired an American stage musical adaptation.

That’s the business case for the series. But there is a more basic question: “Why?” Why this property and why now? It’s a simple test, but many of these projects fail it. Why bother checking in with characters decades later, only to be offered a facile reassurance that these people approaching retirement age are doing exactly what they were doing 20 years earlier? It’s a cultural Neverland.

This is what is most surprising about The Full Monty. The show has its problems: it suffers from the common streaming-age problem that it would work better as a 90-minute movie than an eight-hour miniseries, and many of the episodes would flow easier as half-hour sitcom instalments than hour-long dramedy chapters. However, it gets across the most basic hurdle facing these sorts of revivals. It has that “why”.

Read more

The show opens with a montage providing a refresher on the events of the original movie and bringing the audience to the present day, exploring what it means to join these characters “seven prime ministers” and “eight northern regeneration policies later”. Using that framing device, The Full Monty immediately establishes itself as a show about bridging the Britain of 1997 with that of 2023.

Beaufoy deals directly with contemporary issues: food banks, austerity, immigration, homelessness. Multiple episodes of the show end with closing title cards providing contact numbers for viewers who may struggle with similar problems to those depicted in the series. It retains the light-hearted humanism that made the movie such a breakout success, but it doesn’t shy away from hard realities.

Once again, nostalgia obscures the reality of the original film. Discussion of the movie focus on its warmth. Roger Ebert summarised it as “bawdy, but also gentle and good-hearted”, while Janet Maslin of the New York Times described it as “always generous, never cruel”. However, Maslin astutely argued that The Fully Monty was about how, for its male leads, “joblessness is a humiliation well beyond nakedness”.

The film originated with Beaufoy’s plans to make a documentary about unemployed workers painting the pylons on the Yorkshire Moors, which would become his follow-up project, Among Giants. “It’s a recession comedy,” Beaufoy said of The Full Monty at the opening of a second musical adaptation in 2013. “It was a really grim time, and it was visibly grim.”

Mark Addy returns as Dave. Photo by Ben Blackall via Disney+

“It’s easy to forget that the film is quite heavily political,” remarked Robert Carlyle, a former trade union official. “And I think the same applies to the TV show. These people have lived through what seems like 25 years of austerity.”

The series doesn’t shy away from this. Carlyle’s Gaz is reintroduced carrying his mattress around with him on public transport, looking for a place to sleep, while trying to afford a motorised wheelchair for his grandson, Brian (William Fox).

Some have argued that the original film was so successful in part because it arrived in the wake of a bloated blockbuster summer season packed with overwhelming special-effects-driven spectacle. 1997 was the year of The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Air Force One, Con Air, Batman & Robin, The Fifth Element, Men in Black, Speed 2: Cruise Control and Face/Off.

“It was a summer in which we were presented with movies that had no resemblance to our world or our lives,” offered Lindsay Law, head of Fox Searchlight, by way of explaining the film’s success. “In this movie, the audience actually understands and loves these guys.”

Paul Barber as Horse in The Full Monty. Photo by Ben Blackall via Disney+

This logic applies to this miniseries, emerging into a landscape dominated by similarly bombastic nostalgia-driven event series.

The Full Monty is a rare depiction of working-class life in modern television. While working-class protagonists dominated shows like All in the Family or Married… with Children, critics have noted the erosion of the blue-collar sitcom over the past few decades. Instead, so much modern television depicts a world where, according to writer Wesley Morris, “everybody belongs to the same generic, vaguely upper-class class”.

The television writer Ken Levine has conceded that it has become accepted wisdom within the industry that “working-class sitcoms will seem too depressing”, and the critic Richard Beck has argued that prestige television has pivoted away from depictions of working-class life in favour of shows “targeted at educated professionals”. Beaufoy and his cast have found a way to exploit the modern intellectual property boom to foreground a portrait of modern working-class life.

The Full Monty certainly has its flaws, but — stripped down to its essence — it finds a more convincing raison d’être than most of these nostalgic revivals.

‘The Full Monty’ is on Disney+ from Wednesday, June 14