Trending

In Goa, Climate Change Is Now Real

On a sultry day in Goa’s southernmost Dharbandora taluka, a Fullbright scholar-turned-farmer Sachin Tendulkar looks up at the skies and then at his land. “Never in my life have I seen such poor pre-monsoon showers,” says Tendulkar.

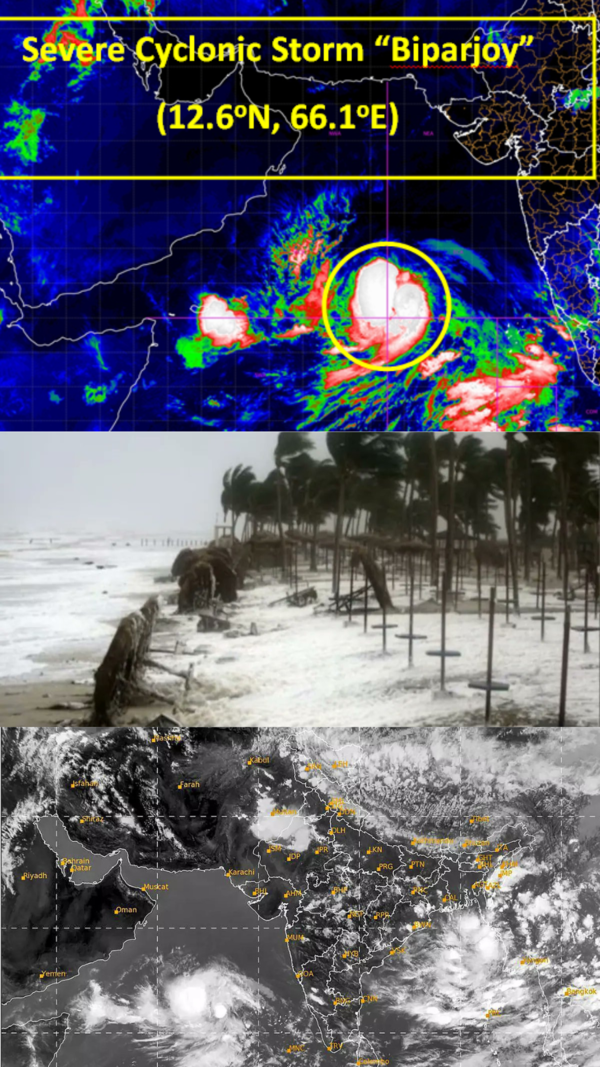

Goa’s wait for rains just got longer as the severe cyclonic storm Biparjoy (pronounced as Biporjoy) brewing in the Arabian Sea skirted the tiny state but pushed rain-bearing clouds further and delayed its onset over Goa to mid-June. Add to it the El Nino effect, where a rise in surface temperature in the Arabian Sea has led to delay in monsoon arrival in the west coast.

“Usually, the El Nino peaks in December. However, this year it can peak by July and August which coincides with the monsoon months in the Indian subcontinent,” says meteorologist and retired NIO scientist M R Ramesh Kumar.

Monsoon is the lifeblood of India’s $3 trillion economy and provides nearly 70% of the rain needed for its farms and to recharge reservoirs and aquifers. Not to speak of the relief it brings from a scorching summer.

Water Resources Department chief engineer Pramod Badami says this extent of delay in monsoon had been seen in Goa around the mid-90s, but he also admits that climate change is a factor this time around.

Need Stabilisation

“In the future, the state government will have to work on stabilising the situation,” says Badami.

But this is exactly what Rajiv Kumar Chaturvedi, a faculty at BITS Goa campus and a UN expert in greenhouse gas emissions inventory, who has studied 117 years of climate data set for Goa had predicted.

“We saw heavy rainfall and rain every month in 2021 in Goa. Now, we are seeing a delayed monsoon in 2023. What we are seeing right now fits well with the trend of climate change. This is what we expected in a climate change scenario,” says Chaturvedi, who along with other experts helped prepare the State Action Plan on Climate Change.

Though data showed that rainfall received in Goa has increased over a period of 100 years, the increase in rainfall has mostly come from extreme rainfall events, he says.

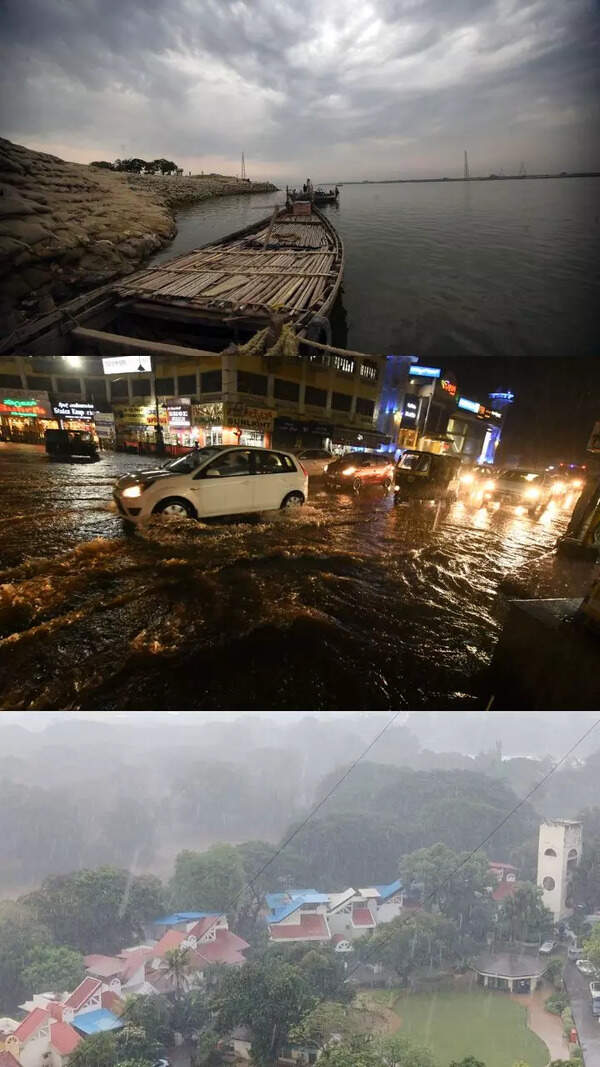

“Rainfall has become erratic and when it happens, it happens in bursts, which is not good, because you can see landslides and landslides happening in newer areas,” says Chaturvedi.

Overall Impact

This has a detrimental impact on the agriculture sector. The fluctuating pattern of rainfall can lead to inundation, prolonged floods, crop spoilage or even soil loosening. “Goa’s agriculture sector requires spatial and temporal distribution of rainfall in order to flourish. Any delay in monsoon or even prolonged breaks in rainfall will cost us not only our crops but also manpower,” say farmers.

Rapid and unplanned urbanisation along with the pressures of climate change are already seeing its impact on water resources. With a population of around 15 lakh, the tourist state sees an inflow between 80 lakh and 1 crore tourists a year, which continues to exert pressure on the natural resources.

“When there is a delay in monsoon, the base flow reduces, springs dry up and river flow reduces. When there are no pre-monsoon showers, groundwater obviously will hit rock bottom. It takes at least 10 inches of rainfall for the groundwater to begin to recharge,” says Badami.

But then, this delay also leads to operational losses. “At first the plants will take in the water and only then the groundwater recharge can start,” he says.

Tendulkar reckons that the WRD’s claims of Goa’s groundwater at “safe” levels is illusionary. “The urban areas are fully dependent on drawing water stored in the reservoirs. Urbanisation is rising and the developmental pressure is moving to the hinterland,” he says.

In Goa, the use of 16,000 litres of water by a household was declared free of cost. “It may be a political decision, but nature does not understand it,” says Tendulkar, who has studied hydrological rejuvenation efforts in Australia.

Scary Future

Depletion and fragmentation of forests will only add to the difficulties in groundwater recharge, which are already staring at rising temperatures due to climate change. The scanty pre-monsoon rainfall and the delayed monsoon onset has only exacerbated the situation.

For instance, this year Goa saw a 74% deficit in the pre-monsoon rainfall in comparison to Gujarat, which received an excess of 863%, while Maharashtra had 100% excess pre-monsoon rain. The entire Indian subcontinent received a total of 12% excess rainfall.

“The deficit is hazardous. Having low rainfall over Goa, especially in May, is almost as bad as a disaster. This is bad for wildlife, agriculture and drinking water,” says Kumar, the former scientist from NIO.

Tendulkar feels that it is high time various government departments worked as a cohesive unit and took note of the climate change seriously and its impact on Goa’s water shortage. “Even some bandharas (structures storing water on the rivers) upstream have been tapped by now. The situation in the future is going to be scary.”

(With inputs from Nida Sayed)

Goa’s wait for rains just got longer as the severe cyclonic storm Biparjoy (pronounced as Biporjoy) brewing in the Arabian Sea skirted the tiny state but pushed rain-bearing clouds further and delayed its onset over Goa to mid-June. Add to it the El Nino effect, where a rise in surface temperature in the Arabian Sea has led to delay in monsoon arrival in the west coast.

“Usually, the El Nino peaks in December. However, this year it can peak by July and August which coincides with the monsoon months in the Indian subcontinent,” says meteorologist and retired NIO scientist M R Ramesh Kumar.

Monsoon is the lifeblood of India’s $3 trillion economy and provides nearly 70% of the rain needed for its farms and to recharge reservoirs and aquifers. Not to speak of the relief it brings from a scorching summer.

Water Resources Department chief engineer Pramod Badami says this extent of delay in monsoon had been seen in Goa around the mid-90s, but he also admits that climate change is a factor this time around.

Need Stabilisation

“In the future, the state government will have to work on stabilising the situation,” says Badami.

But this is exactly what Rajiv Kumar Chaturvedi, a faculty at BITS Goa campus and a UN expert in greenhouse gas emissions inventory, who has studied 117 years of climate data set for Goa had predicted.

“We saw heavy rainfall and rain every month in 2021 in Goa. Now, we are seeing a delayed monsoon in 2023. What we are seeing right now fits well with the trend of climate change. This is what we expected in a climate change scenario,” says Chaturvedi, who along with other experts helped prepare the State Action Plan on Climate Change.

Though data showed that rainfall received in Goa has increased over a period of 100 years, the increase in rainfall has mostly come from extreme rainfall events, he says.

“Rainfall has become erratic and when it happens, it happens in bursts, which is not good, because you can see landslides and landslides happening in newer areas,” says Chaturvedi.

Overall Impact

This has a detrimental impact on the agriculture sector. The fluctuating pattern of rainfall can lead to inundation, prolonged floods, crop spoilage or even soil loosening. “Goa’s agriculture sector requires spatial and temporal distribution of rainfall in order to flourish. Any delay in monsoon or even prolonged breaks in rainfall will cost us not only our crops but also manpower,” say farmers.

Rapid and unplanned urbanisation along with the pressures of climate change are already seeing its impact on water resources. With a population of around 15 lakh, the tourist state sees an inflow between 80 lakh and 1 crore tourists a year, which continues to exert pressure on the natural resources.

“When there is a delay in monsoon, the base flow reduces, springs dry up and river flow reduces. When there are no pre-monsoon showers, groundwater obviously will hit rock bottom. It takes at least 10 inches of rainfall for the groundwater to begin to recharge,” says Badami.

But then, this delay also leads to operational losses. “At first the plants will take in the water and only then the groundwater recharge can start,” he says.

Tendulkar reckons that the WRD’s claims of Goa’s groundwater at “safe” levels is illusionary. “The urban areas are fully dependent on drawing water stored in the reservoirs. Urbanisation is rising and the developmental pressure is moving to the hinterland,” he says.

In Goa, the use of 16,000 litres of water by a household was declared free of cost. “It may be a political decision, but nature does not understand it,” says Tendulkar, who has studied hydrological rejuvenation efforts in Australia.

Scary Future

Depletion and fragmentation of forests will only add to the difficulties in groundwater recharge, which are already staring at rising temperatures due to climate change. The scanty pre-monsoon rainfall and the delayed monsoon onset has only exacerbated the situation.

For instance, this year Goa saw a 74% deficit in the pre-monsoon rainfall in comparison to Gujarat, which received an excess of 863%, while Maharashtra had 100% excess pre-monsoon rain. The entire Indian subcontinent received a total of 12% excess rainfall.

“The deficit is hazardous. Having low rainfall over Goa, especially in May, is almost as bad as a disaster. This is bad for wildlife, agriculture and drinking water,” says Kumar, the former scientist from NIO.

Tendulkar feels that it is high time various government departments worked as a cohesive unit and took note of the climate change seriously and its impact on Goa’s water shortage. “Even some bandharas (structures storing water on the rivers) upstream have been tapped by now. The situation in the future is going to be scary.”

(With inputs from Nida Sayed)

About the Author

Gauree MalkarnekarGauree Malkarnekar, senior correspondent at The Times of India, Goa, maintains a hawk's eye on Goa's expansive education sector. And when she is not chasing schools, headmasters and teachers, she turns her focus to crime. Her entry into journalism was purely accidental: a trained commercial artist, she landed her first job as a graphic designer with a weekly, but less than a fortnight later set aside the brush and picked up the pen. Ever since she has not complained.

Start a Conversation

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

FacebookTwitterInstagramKOO APPYOUTUBE