Trending Topics

Fonts of joy

They are veritable oases during the scorching summer months, drawing visitors and locals alike. It is only natural then that Goa’s springs need to be protected for posterity

...

There was a time when the sweltering summer heat drove people to natural springs gurgling with delightfully cool and limpid water. Now, although bigger sources such as waterfalls and shallow rock pools in the upper reaches of rivers have become more popular, many still swear by the purported medicinal value of fresh spring water.

While seaside trips offered most Goans a chance to relax, soak in the balmy breezes and wallow in salty water in the bygone days, it was the fonts meandering through lush green slopes and running down rocky terrain that were – and still are – more fascinating for hordes of picnickers. During an era when mobility and accessibility were limited, people didn’t mind trekking long distances to such springs for a cool bath. The tranquil ambiences only added to a truly relaxing experience.

“I have been visiting the Pomburpa spring daily for about a month now, except on Sundays when it is crowded, and I bathe in short spells for about an hour and half,” said Sunil Vaigankar, a resident of nearby Nachinola.

Haphazard development, neglect and other related factors have triggered the degradation of many springs, causing them to dry up or even wiping them off completely. Fortunately, a few frequented ones such as Kesarval near the Verna industrial estate, Saligao’s Salmona spring, Pomburpa, and Takazhor at Rivona have managed to survive.

“A spring is essentially groundwater emerging as surface water. If groundwater is contaminated or overexploited, or the recharge area is reduced, it impacts intensity of the spring’s flow and water quality,” former chief engineer of the state’s water resources department, S T Nadkarni, said.

Many springs at the base of hills – either seasonal or perennial – now have depleted flow due to developmental activity in their vicinity. Rivona’s Takazhor, however, is one of the few to be unaffected as the plateau from which it emanates has remained untouched. Thronged by visitors, it has five large flows that enable several people to bathe simultaneously. The milky white water that rushes down, and its distinct taste somewhat like raw buttermilk, probably lent it the name Takazhor – ‘tak’ meaning buttermilk in Konkani, villagers said.

“Top soil denudation greatly affects springs. In places like Merces, a popular spring is now deserted due to sewage influx. But springs in many comunidade properties have been protected,” Hector Fernandes, a geologist, said.

Unbeknownst to many, springs have a magical effect on large waterbodies. They feed lakes, rivers, and finally, the sea, thereby playing a vital role in sustaining life.

In Goa, for instance, life revolved around springs before the advent of tap water. These natural fonts were used for drinking, bathing, washing clothes, minor irrigation, and even as watering holes for livestock.

They were particularly well-maintained during the Portuguese era. Bainguinim spring, which skirts Old Goa, was once a popular source that not only met the former capital’s water needs but was also a place for high society and locals to relax.

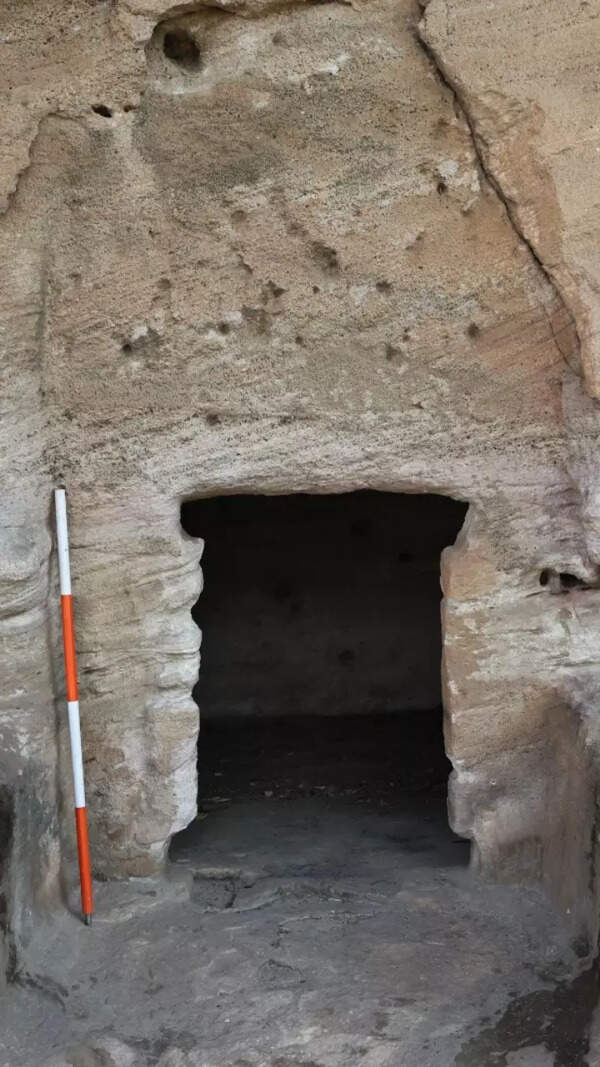

Unique springs also dot Goa’s landscape, some of them famed for their medicinal properties and ability to heal eye and skin problems. Among these are Phoenix and Boca de Vaca, both of which lie in the heart of the state capital, Panaji. “The groundwater from the plateau above these springs has been trapped for storage, forming a horizontal well (qanat). This is a Persian concept and was possibly built when Goa traded with the Persians,” Nadkarni said.

Takazhor in Rivona is believed to cure mental ailments if one bathes in it three to four times, according to the village elders.

Keen on protecting these natural delights, the Goa Tourism Development Corporation has spent several lakhs of rupees in building infrastructure, beautifying, and setting up changing rooms for visitors at popular springs such as Kesarval and Pomburpa. But rowdy elements and visitors lacking civic sense have messed up both.

“Such springs are nature’s gift to us. The government has done its bit in protecting them, but shouldn’t we do ours?” Colva-based Mariano Crasto, who was visiting Kesarval spring, said.

While hydrogeologists have found spring water to be potable in many areas due to copious rainfall and the permeable nature of laterite soil, they’ve advised frequent tests for pollution. Environmental activist Dattaram Desai said most springs in Savoi-Verem, for instance, are in good condition as they are used for irrigation. “The vent of the springs, from where the water flows, should be cleaned up annually, as leaves and other litter can choke the flow,” he said.

Nadkarni and others have also suggested the identification and protection of the recharge areas of springs if they are to gurgle and gush and continue to replenish and rejuvenate for posterity.

Inputs by Govind Kamat Maad

x-x-x-x-x-x

GUSHING WITH GOODNESS

* Goa has more than 500 springs, mostly in hilly regions

* Ponda is among the hotspots of these fonts

* Many swear by the medicinal properties of spring water in curing eye, skin and other health problems

* Several springs irrigate kulagars – orchards at the base of hills – and are comparatively better maintained

* The PWD also tapped the Dabe and Arambol springs for potable water at one point

...

There was a time when the sweltering summer heat drove people to natural springs gurgling with delightfully cool and limpid water. Now, although bigger sources such as waterfalls and shallow rock pools in the upper reaches of rivers have become more popular, many still swear by the purported medicinal value of fresh spring water.

While seaside trips offered most Goans a chance to relax, soak in the balmy breezes and wallow in salty water in the bygone days, it was the fonts meandering through lush green slopes and running down rocky terrain that were – and still are – more fascinating for hordes of picnickers. During an era when mobility and accessibility were limited, people didn’t mind trekking long distances to such springs for a cool bath. The tranquil ambiences only added to a truly relaxing experience.

“I have been visiting the Pomburpa spring daily for about a month now, except on Sundays when it is crowded, and I bathe in short spells for about an hour and half,” said Sunil Vaigankar, a resident of nearby Nachinola.

Haphazard development, neglect and other related factors have triggered the degradation of many springs, causing them to dry up or even wiping them off completely. Fortunately, a few frequented ones such as Kesarval near the Verna industrial estate, Saligao’s Salmona spring, Pomburpa, and Takazhor at Rivona have managed to survive.

“A spring is essentially groundwater emerging as surface water. If groundwater is contaminated or overexploited, or the recharge area is reduced, it impacts intensity of the spring’s flow and water quality,” former chief engineer of the state’s water resources department, S T Nadkarni, said.

Many springs at the base of hills – either seasonal or perennial – now have depleted flow due to developmental activity in their vicinity. Rivona’s Takazhor, however, is one of the few to be unaffected as the plateau from which it emanates has remained untouched. Thronged by visitors, it has five large flows that enable several people to bathe simultaneously. The milky white water that rushes down, and its distinct taste somewhat like raw buttermilk, probably lent it the name Takazhor – ‘tak’ meaning buttermilk in Konkani, villagers said.

“Top soil denudation greatly affects springs. In places like Merces, a popular spring is now deserted due to sewage influx. But springs in many comunidade properties have been protected,” Hector Fernandes, a geologist, said.

Unbeknownst to many, springs have a magical effect on large waterbodies. They feed lakes, rivers, and finally, the sea, thereby playing a vital role in sustaining life.

In Goa, for instance, life revolved around springs before the advent of tap water. These natural fonts were used for drinking, bathing, washing clothes, minor irrigation, and even as watering holes for livestock.

They were particularly well-maintained during the Portuguese era. Bainguinim spring, which skirts Old Goa, was once a popular source that not only met the former capital’s water needs but was also a place for high society and locals to relax.

Unique springs also dot Goa’s landscape, some of them famed for their medicinal properties and ability to heal eye and skin problems. Among these are Phoenix and Boca de Vaca, both of which lie in the heart of the state capital, Panaji. “The groundwater from the plateau above these springs has been trapped for storage, forming a horizontal well (qanat). This is a Persian concept and was possibly built when Goa traded with the Persians,” Nadkarni said.

Takazhor in Rivona is believed to cure mental ailments if one bathes in it three to four times, according to the village elders.

Keen on protecting these natural delights, the Goa Tourism Development Corporation has spent several lakhs of rupees in building infrastructure, beautifying, and setting up changing rooms for visitors at popular springs such as Kesarval and Pomburpa. But rowdy elements and visitors lacking civic sense have messed up both.

“Such springs are nature’s gift to us. The government has done its bit in protecting them, but shouldn’t we do ours?” Colva-based Mariano Crasto, who was visiting Kesarval spring, said.

While hydrogeologists have found spring water to be potable in many areas due to copious rainfall and the permeable nature of laterite soil, they’ve advised frequent tests for pollution. Environmental activist Dattaram Desai said most springs in Savoi-Verem, for instance, are in good condition as they are used for irrigation. “The vent of the springs, from where the water flows, should be cleaned up annually, as leaves and other litter can choke the flow,” he said.

Nadkarni and others have also suggested the identification and protection of the recharge areas of springs if they are to gurgle and gush and continue to replenish and rejuvenate for posterity.

Inputs by Govind Kamat Maad

x-x-x-x-x-x

GUSHING WITH GOODNESS

* Goa has more than 500 springs, mostly in hilly regions

* Ponda is among the hotspots of these fonts

* Many swear by the medicinal properties of spring water in curing eye, skin and other health problems

* Several springs irrigate kulagars – orchards at the base of hills – and are comparatively better maintained

* The PWD also tapped the Dabe and Arambol springs for potable water at one point

About the Author

Paul FernandesPaul Fernandes, assistant editor (environment) at The Times of India, Goa, has more than two decades of experience behind him. He writes on social, environmental, heritage, archaeological and other issues. His hobbies are music, trekking, adventure and sports, especially football.

Start a Conversation

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

FacebookTwitterInstagramKOO APPYOUTUBE