This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

SOUR LAKE -- Beverly Carrier-Walters still remembers being in elementary school in the 1960s, before the schools in Hardin-Jefferson ISD were integrated.

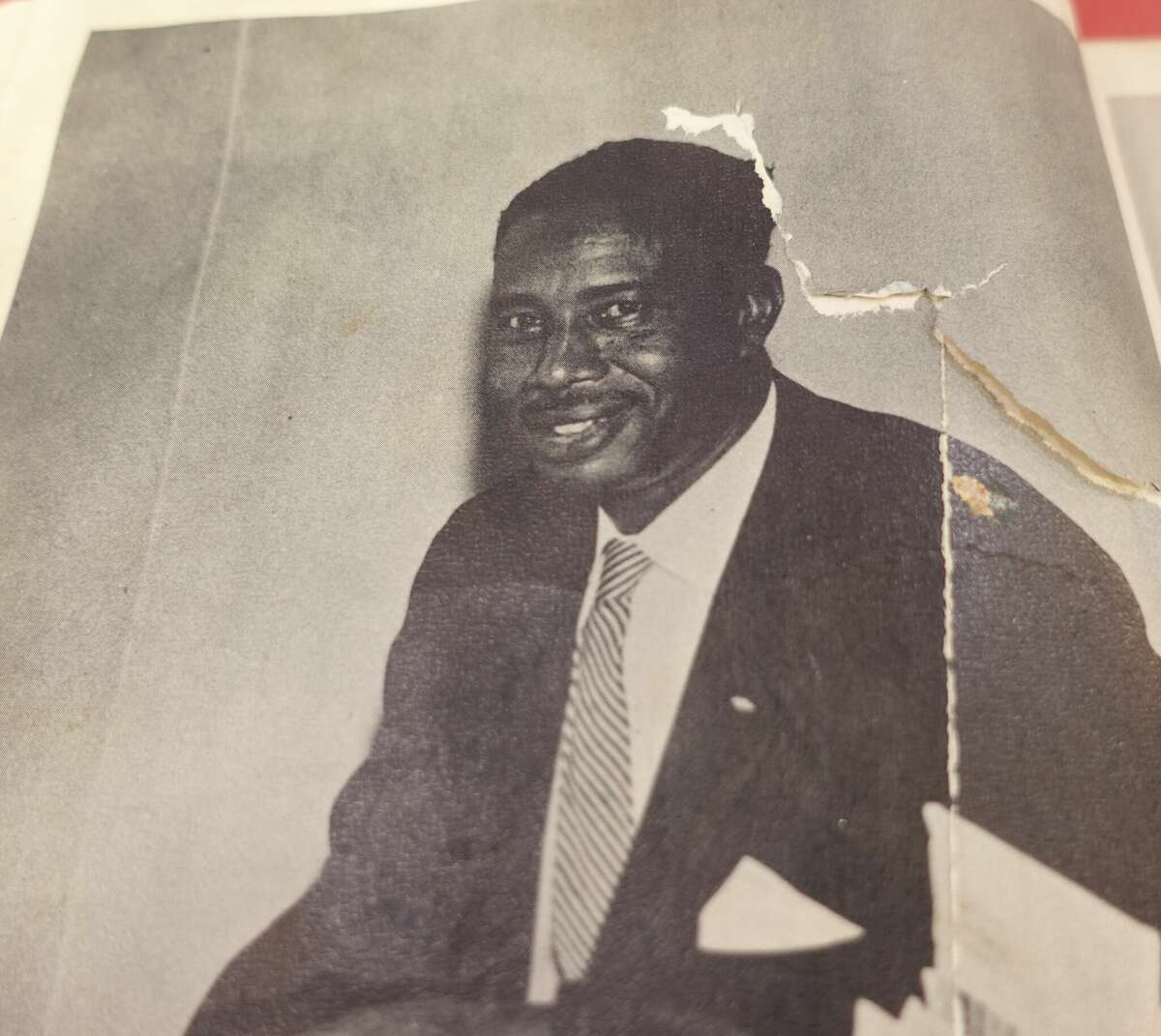

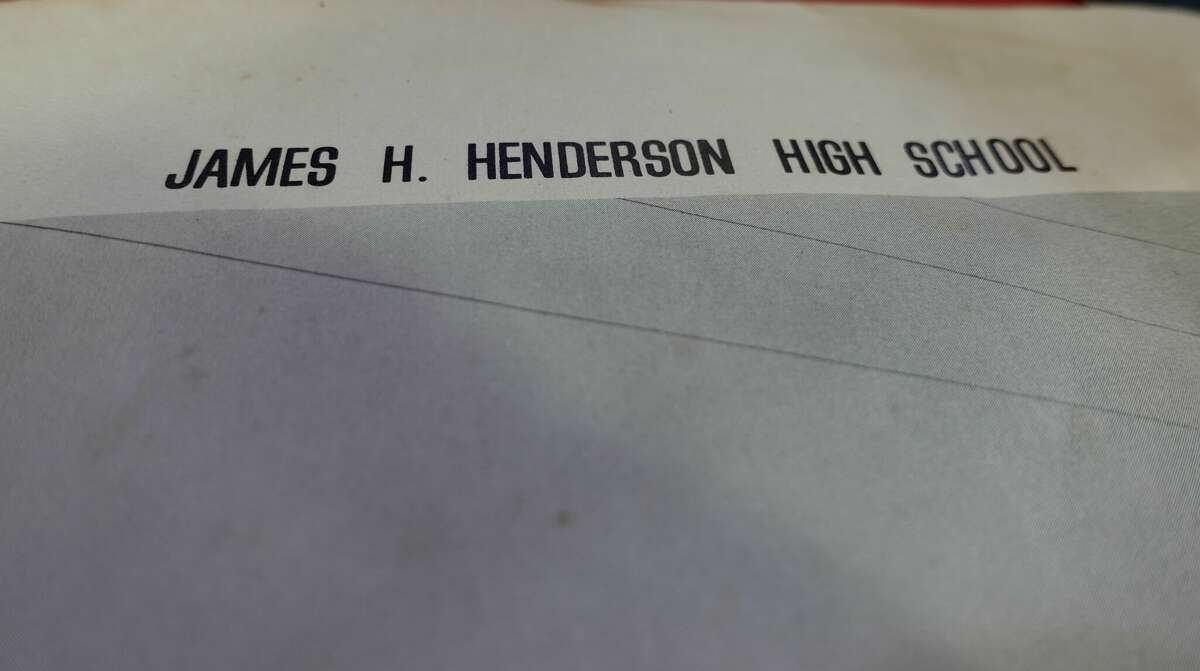

Then known as "Henderson School," the school served the Black elementary and high school students of China, Nome and Sour Lake. James H. Henderson was the school's principal and the first Black principal. His visits to classrooms were akin to Santa Claus visiting your home on Christmas, Carrier-Walters said.

"He used to pop in and out of the classrooms, and I remember the teacher telling us, 'OK, it's almost time for Mr. Henderson to come in, be on your best behavior,'" she said. "We would be so excited. He would come in and speak to us, make sure we're doing our lessons, make sure we listen to our teacher, make sure we're using good manners."

Carrier-Walters recalls the fun memories and how Henderson always made the students feel special and appreciated.

"He would always say, 'Children, you have done a good job, I'm very proud of you,'" she said. "As a small child, to hear somebody tell you that they're proud of you, that means a lot."

When Carrier-Walters was in fifth grade, the schools were integrated and Henderson led the way in making sure it was a peaceful transition for all, she said.

"(He) brought us into the auditorium and he (told) us the white kids will be coming to school with us, but we have nothing to fear because we're going to find best friends for life," she said. "And it's true, I found best friends for life. He wanted a peaceful transition...he was very instrumental in bringing the Black and the white community together."

Henderson's impact on the district had already been felt before his role in the integration process. The school he had overseen for years -- previously known as "China Colored School" -- was renamed "Henderson School." After integration, it became an elementary school that he was selected to lead again, according to Beaumont Enterprise archives.

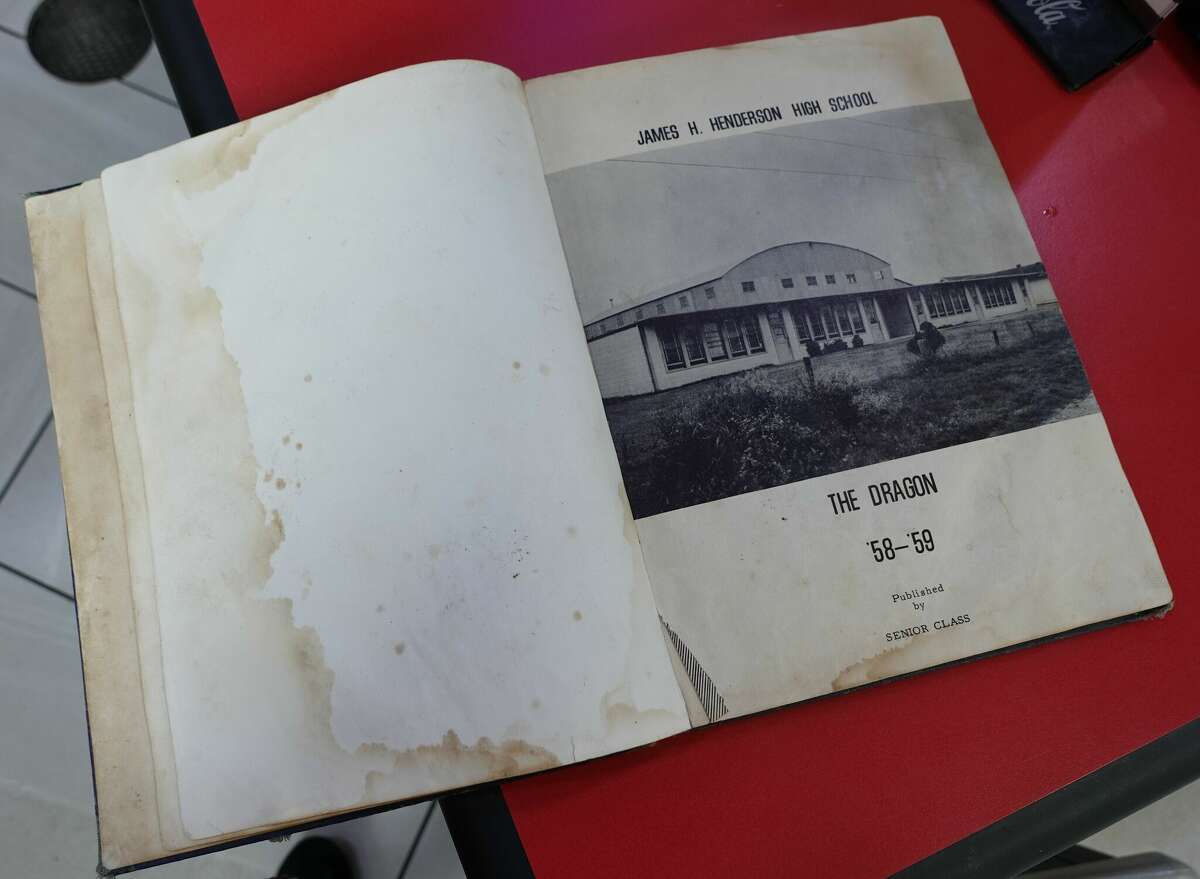

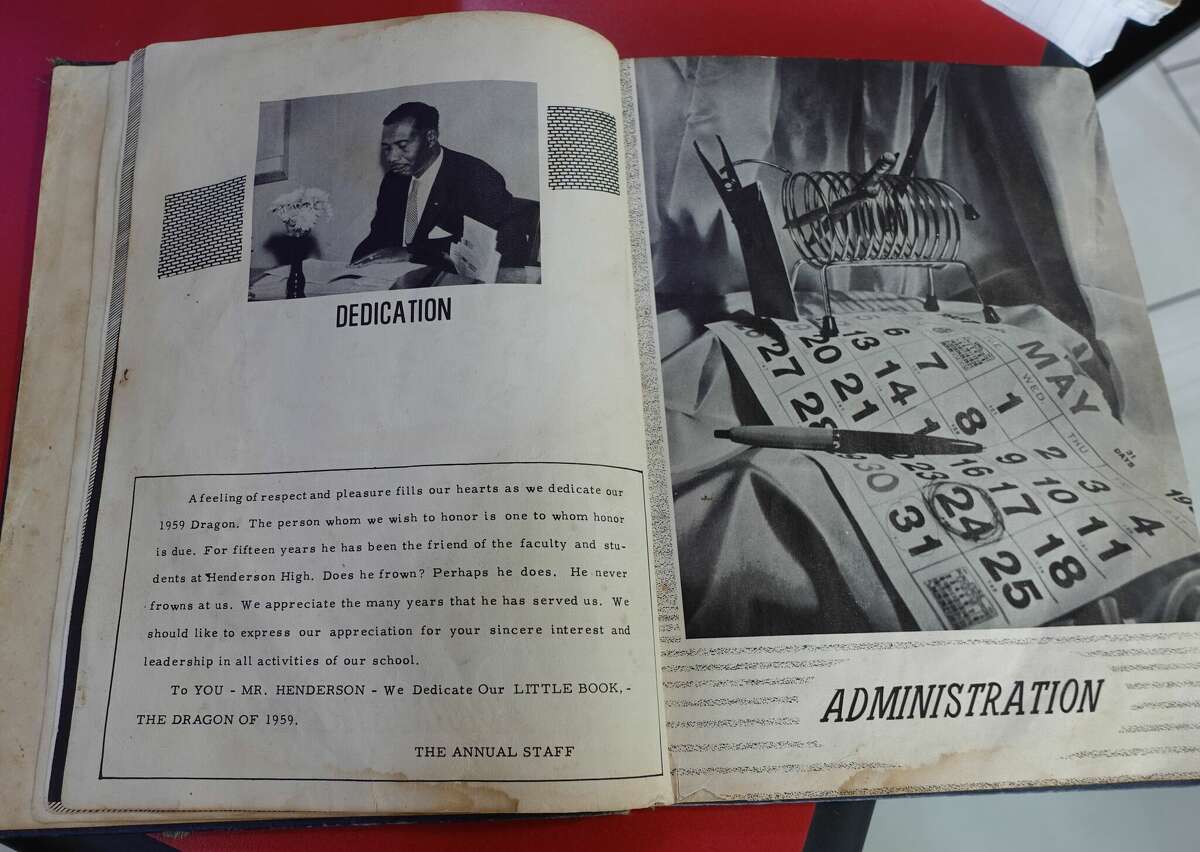

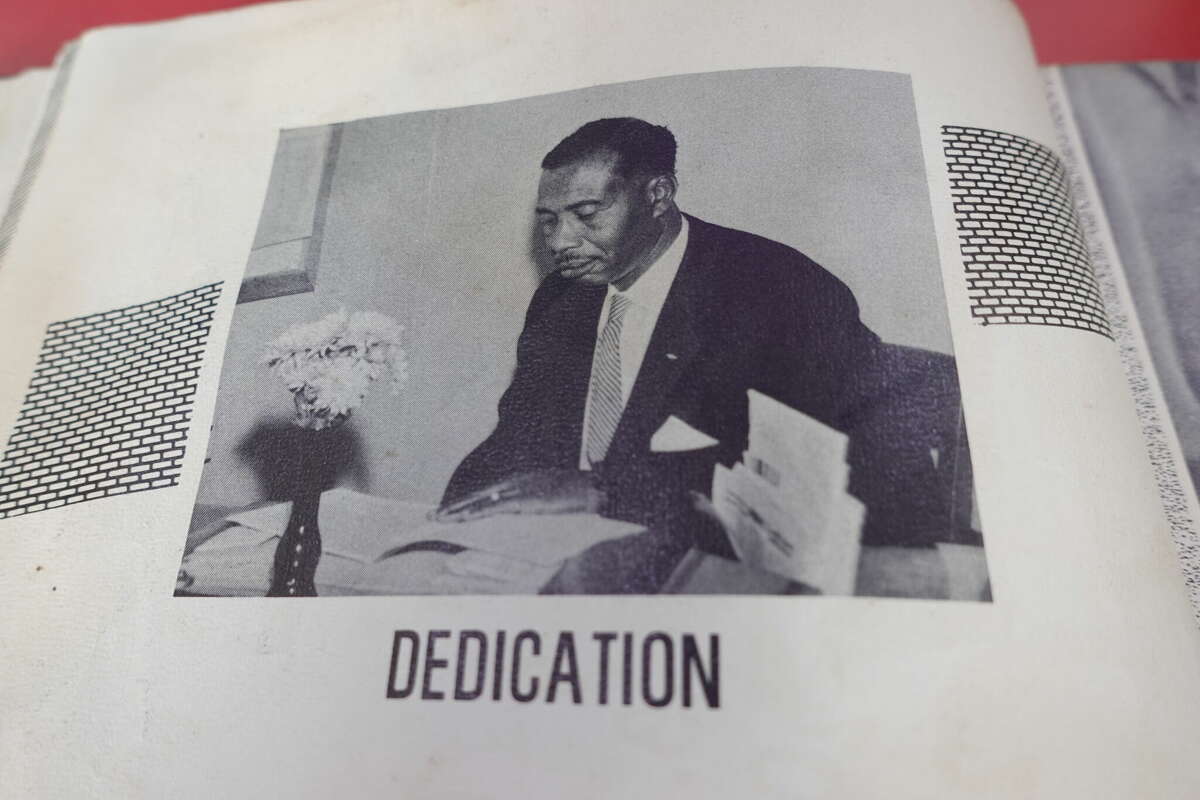

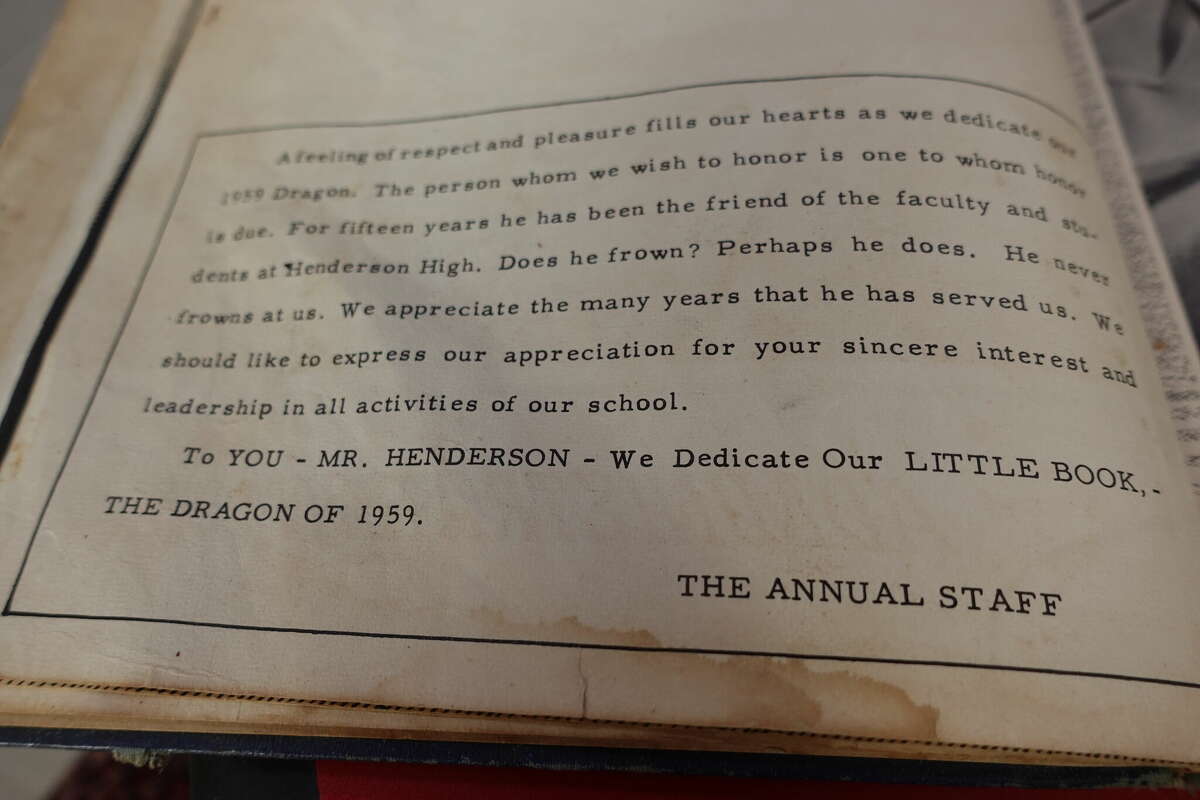

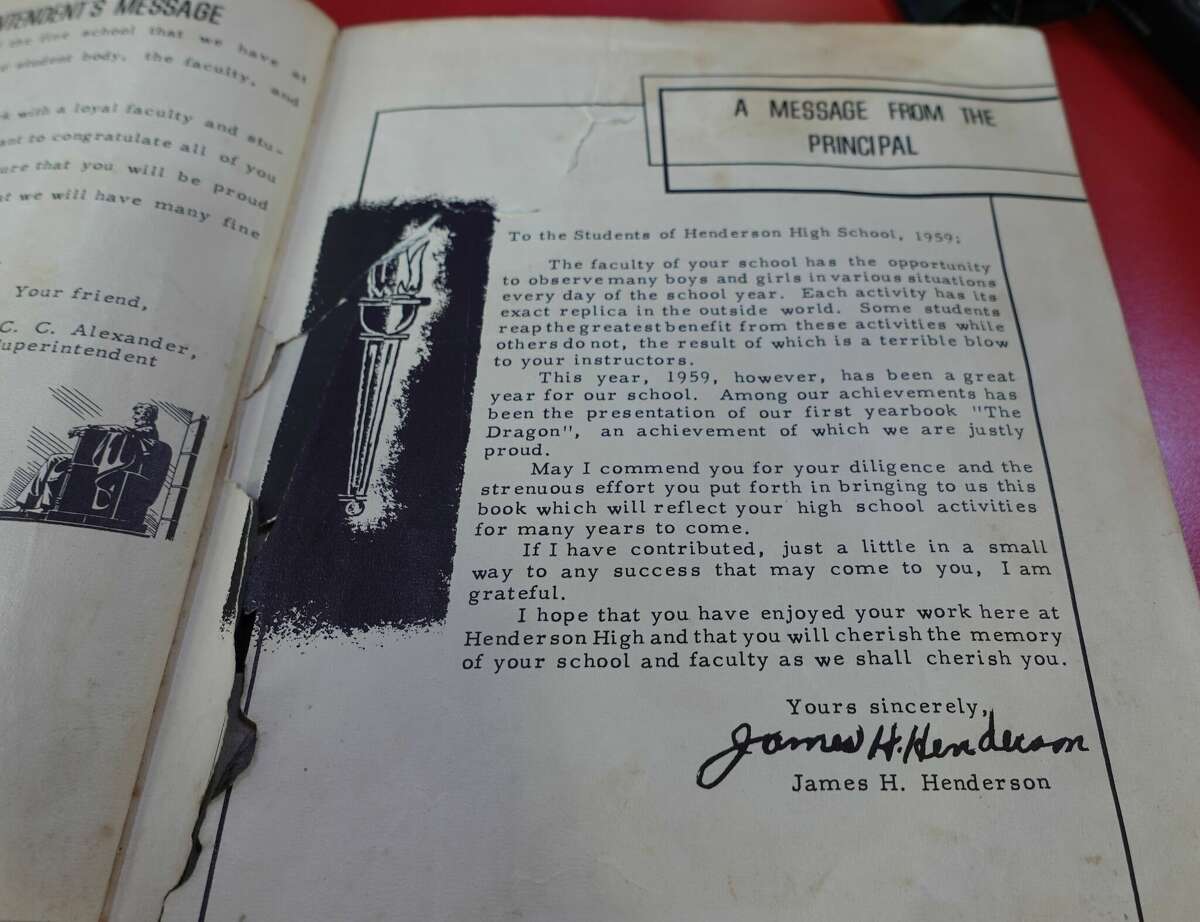

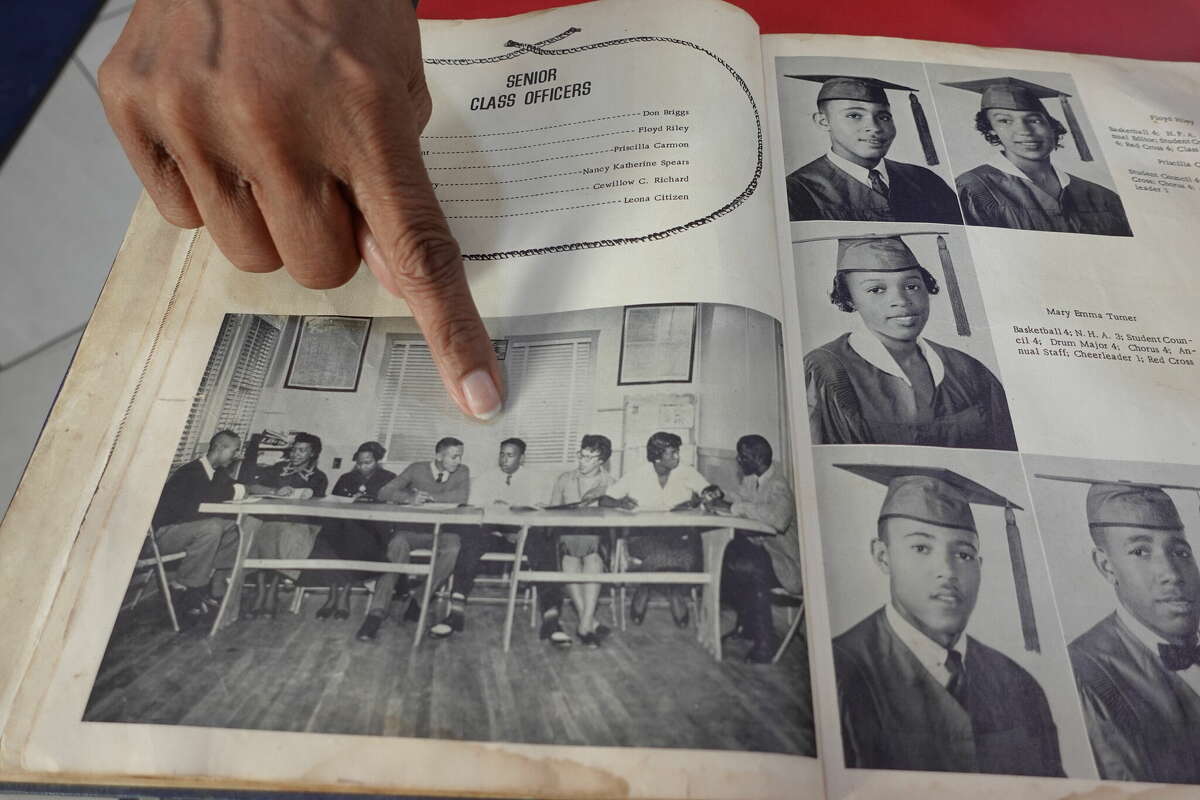

The first yearbook of Henderson High School, The Dragon of 1959, was dedicated to Henderson by the senior class, exemplifying his impact on his pupils.

"For 15 years, he has been the friend of the faculty and students at Henderson High," the dedication reads. "Does he frown? Perhaps he does. He never frowns at us. We appreciate the many years that he has served us."

At his retirement in May 1973 after working for the district for 29 years, Henderson recalled his journey, "I was the only Black high school principal to survive (integration)," he said.

His name has adorned schools in Hardin-Jefferson ISD for some 60 years -- first an elementary, then a junior high and now the present Henderson Middle School.

But that tenure was cut short in March when the Hardin-Jefferson ISD school board voted to change the name to "Hardin-Jefferson Junior High," in an effort to "align the name of our new middle school building with the other campuses in our district," said district Director of Communications Mandy Fortenberry in a statement to The Enterprise.

The building that housed Henderson Middle School for years was destroyed by flooding from Tropical Storm Harvey in 2017. As the district looks to complete the new building, funded in part by a $21.25 million bond passed in 2020, Henderson's name will not be affixed to it.

However, community members such as Carrier-Walters and Claudia Tyler, a longtime China resident whose mother, children and grandchildren attended Henderson, say that when they voted for the bond in 2020, they voted to rebuild Henderson, not Hardin-Jefferson Junior High.

"They did a bond and (applied) for grants and used (Henderson's name) for that, they did a groundbreaking on the Henderson Middle School...and now that the school is almost finished, they changed the name," Tyler said.

The name change came as a surprise to both Carrier-Walters and Tyler, who only found out about it through their grandchildren.

"I was totally shocked," Carrier-Walters said. "To take that legacy away from us, I think it's a shame."

Henderson was more than just a principal, he was a community leader, Tyler said.

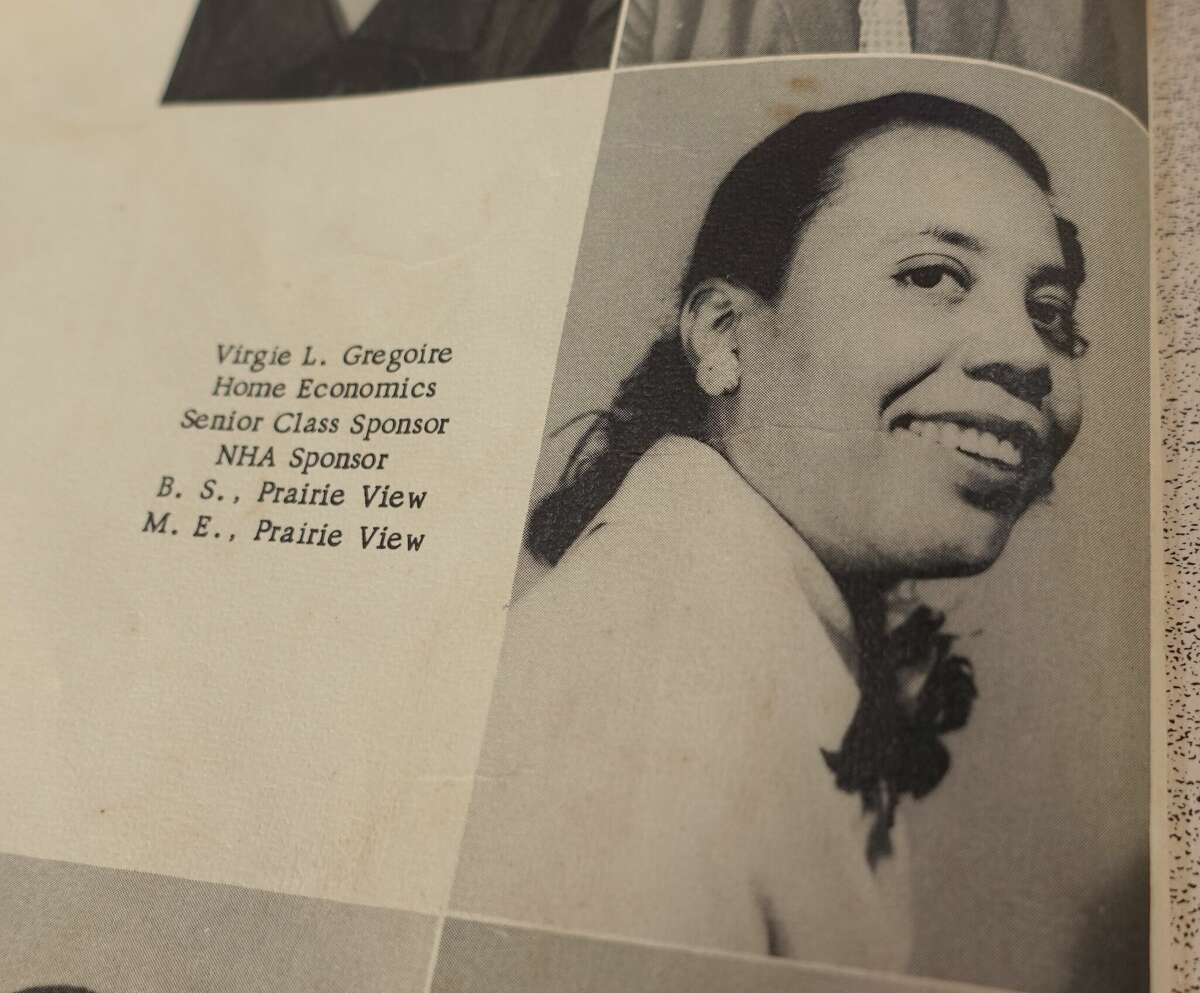

"He told our parents, 'You can do it, you can go to college and bring something back to the community,'" she said. "My aunt, Virgie Gregoire, she went to Prairie View, graduated -- she could have went anywhere to teach, and she came back and taught here. (Henderson) was always going to my grandparents' home, and they'd have coffee and he'd discuss his plans on what he wanted for the kids in the community. So, he was proud when they came back and gave back to the community. Being a Black woman at that time with a degree, you might say to yourself 'I'm going to spread my wings, I'm not going back home.' But she chose to come back."

Upon his retirement, it was obvious that Henderson was a valued member of the community. He was gifted a TV set and a gold watch by students and faculty. Tributes to him by coworkers didn't leave a dry eye in the house as people recalled his passion for his work, according to a May 24, 1973 article in The Enterprise.

And his road to that position wasn't an easy one. Born just outside of the unincorporated community of Blanchard in Polk County, Henderson worked in cotton and corn fields in his adolescence and had to walk five miles to school each way.

"I could count the stars through the top of the house," Henderson said in the article.

Opportunities for education, much less higher education, were slim, but he persisted.

"I was willing to pay the price," Henderson said. "Others wouldn't and dropped out of school."

He attended Texas College and began teaching with his wife in Groveton in Trinity County. Henderson remained in East Texas, but not all were happy to see a Black man succeed. After he a bought a new car from a coworker in 1938, Henderson was pulled over by a group of white people who threatened him with a gun.

RELATED: School's razing revives memories

"I begged for my life, I thought they would kill me," he recalled. "They couldn't stand to see a Black man in a fine car."

Henderson was directed to drive down a dirt road and then to drive off into a deep ditch. The group then drove away and a truck pulled him out of the ditch. Henderson later sold the car.

Despite the struggle, Henderson moved further south, working in Warren and Beaumont at Charlton-Pollard before securing his job at China in 1944, where he spent the rest of his career.

He didn't stop learning, either. He obtained a bachelor's degree from Texas College in 1942 and later earned a master's degree from the University of Colorado in 1952.

"He wanted unity, he stood for unity," Carrier-Walters said. "He wanted us to be the best of us. You would see him in the hall and he would pat you on the back and say, 'Are you having a good day? Are you doing good?' When we went to lunch, he'd make sure we'd thank the cafeteria ladies. He thought of everything."

Henderson is an important figure in local history, for people of all races and ethnicities, Carrier-Walters said.

"This is not a Black and white issue at all, nor do we want to make it a Black and white issue, because Mr. Henderson would not have wanted that," she said. "When the white kids came over to Henderson (School) and the Black kids went over to the elementary school, we became one and everybody was treated right. It's just not about that -- it's about a legacy that has been taken away from the Blacks as well as the whites...we feel like our legacy has been taken away from us."

Since discovering the name change, Carrier-Walters and Tyler have been notifying other alumni and community members, and they said many people were unaware the change was even being considered.

"They said, 'No, that's not possible. We didn't have a meeting on that. We didn't have a vote on that,'" Tyler said. "I don't think (the school board) thought it would get this large, but there's a lot of people that (are) not happy with this at all. And to find out this way, after the decision has already been made, it's just not fair."

While the name has already been changed, Carrier-Walters and Tyler plan to make public comments at Hardin-Jefferson's regular school board meeting at 6 p.m. Monday, and encourage other community members to show their support. The board meeting will be held in the district's Administration Building, located at 520 W Herring St. in Sour Lake.

"We just want the name back on the school," Carrier-Walters said. "We're just inundated with calls, not only from Blacks, (but) from whites, Hispanics...Since the school integrated a long time ago, (some people) have had the chance to have at least three generations of their families come through there. It's not just a name."

Walters started a change.org petition, which had just under 230 signatures as of 4:30 p.m. Friday. Under the "Reasons for signing" portion, one signee wrote, "Taking away the existing honor of having a building named after (Henderson) is like saying his contributions no longer have value. This was too big a change to do without community input. The board needs to reverse its decision."

In the district's statement to The Enterprise, Fortenberry said that the school board is "currently looking into alternate ways to honor Mr. Henderson, as well as other past employees."

But in Carrier-Walters' and Tyler's opinions, there is no other way to honor Henderson.

"They threw him down to 'honor him and others' -- yes, we have a lot of people in this community that have done a wonderful job here, but nobody carries on their shoulders what he carried on his shoulders," Tyler said. "They can't put these two people together and say they did the same thing. You can't honor him (any better way) than for him to have his name (on the school)."