Tubular Bells and its debt to Richard Branson... and the devil

A teenage Mike Oldfield received countless rejections for his anti-commercial debut before the music impresario took a chance on it and The Exorcist propelled it to iconic status

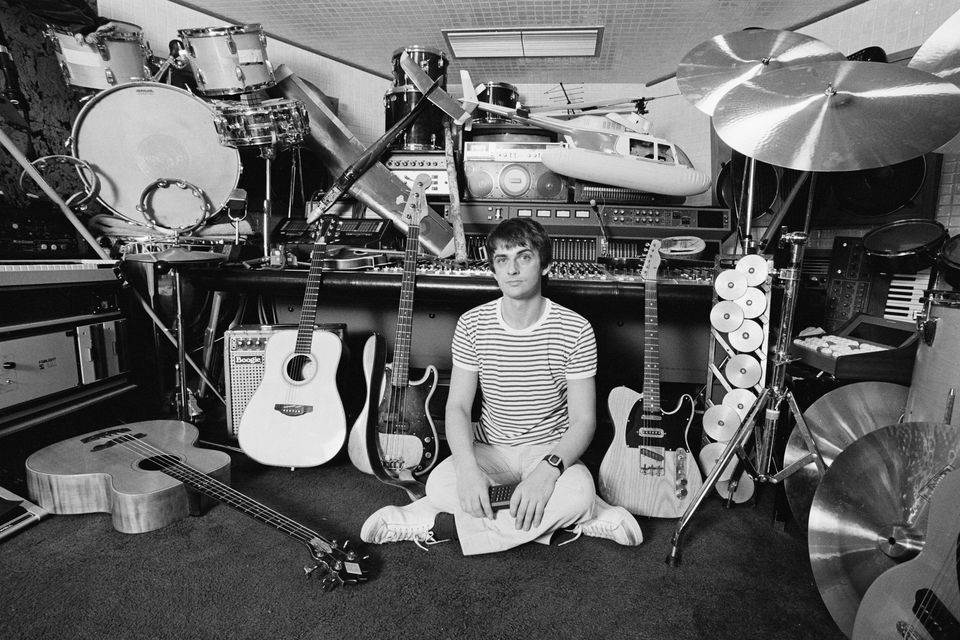

Mike Oldfield lost count of the rejections. One record company after another politely declined to sign the precocious, single-minded 19-year-old. The instrumental music he had submitted was certainly different from the usual fare they received, but none could see it as a commercial proposition.

He would eventually find a home in the fledgling label of another wunderkind, Richard Branson, and the album in question, Tubular Bells — released 50 years ago this month — would go on to sell about 15 million copies worldwide. Some 2.7 million of those were in the UK, making it one of the all-time biggest sellers there. The album was, by any measure, a sensation — a cultural touchstone of the early 1970s that helped give birth to a genre that would soon become known as New Age.

Years later, the Berkshire native — whose nurse mother, Maureen Liston, was from Charleville, Co Cork — mentioned that he had been curious about what happened to the record-company personnel who had turned him down. “I did once spend half an hour Googling the A&R men who booted me out the door, thinking I was a complete nutcase,” he said. “I couldn’t find any of them. I imagine that once Tubular Bells got to No 1, they probably got the sack.

“I suppose it’s an unenviable job — choosing signings for record labels,” he added, a little more charitably. “They obviously wanted to play it safe and sign acts that were like ones that were already selling. But it’s always the outsider, the black sheep, that becomes the blockbuster.” Oldfield certainly was a black sheep.

Tubular Bells by Mike Oldfield

Half a century on, listening to Tubular Bells now, one has sympathy with those who were so unwilling to take a punt. The two lengthy tracks are practically uncategorisable — the first one,Tubular Bells Pt I, meanders wildly, constantly shape-shifting. The section towards the end, which features Viv Stanshall of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band listing all the instruments that went into its creation, sounds utterly unlike the track’s famous opening bars. The second track, Tubular Bells Pt II, features ferocious animal-like growling from Oldfield, and what sounds like a wolf howling, over an increasingly frenetic rock wig-out.

Oldfield has cheerfully talked about the large quantities of drugs that went into the album’s creation. It certainly sounds like something that could only have been made while under the influence. His vision was comparatively straightforward, though: combine many of the tropes of classical music with the then increasingly popular genre of progressive rock.

Remarkably, much of the music began life when he was just 14 or 15. His mother was an alcoholic and he shut himself away in the loft of his home near Reading and composed. He played every instrument himself.

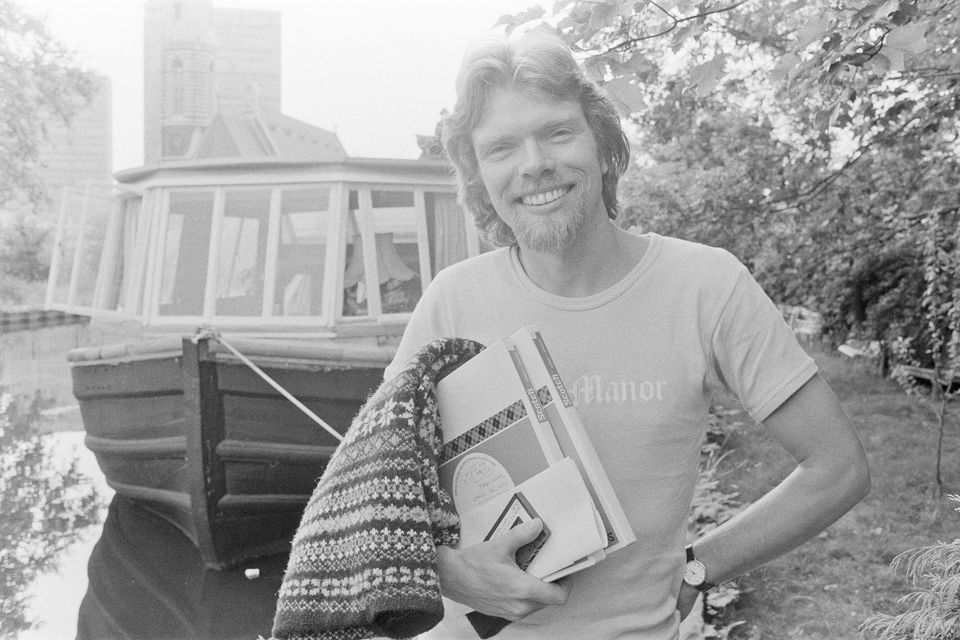

Oldfield’s early success is inextricably linked with that of Branson who, in turn, has to thank the musician for delivering him his first millions. The serial entrepreneur had been making serious money from the age of 16, having first founded a magazine called Student and then opened a record shop in London’s Oxford Street, but it was Tubular Bells that would really put him on the map.

Branson’s path would cross with Oldfield’s shortly after opening a residential recording studio, the Manor, in rural Oxfordshire in 1972. “One day,” Branson later recalled, “an engineer from the Manor rang me and said he’d heard this incredible instrumental demo tape by a teenager called Mike Oldfield. It was some of the most beautiful music I’d ever heard.”

At that time, Oldfield was unhappily serving as second reserve guitarist in the West End production of Hair. He was already disillusioned by the record-company rejections. Branson thought he would have better luck, but the closest he got was with Mercury, who insisted they would only release the music if Oldfield sang conventional vocals. He refused.

Undeterred, Branson decided to release the album himself on his new label. He invited Oldfield to the Manor to record the music properly. Much of the musician’s focus was perfecting the striking opening motif. It had been inspired by the American minimalist composer Terry Riley.

“It was very fashionable not to have everything in 4/4 [time signature],” Oldfield later recalled, “so I made one bar seven beats and one bar eight and then later realised that it had the complexity of Eastern music, the repetitiveness of Terry Riley and the technique of Bach. It just turned out by accident that it was a very nice listenable thing.”

Despite his initial excitement, Branson was alarmed when he heard Oldfield’s completed version of the album. Now that he would have to put his own money behind the release, the reality of trying to sell such uncommercial music left him stumped. Getting the entrepreneur to release the music was, in the words of Tom Newman, the Manor Studio engineer who had notified Branson of Oldfield’s talent, like “dragging stuff uphill through treacle”.

Branson was finally convinced and on May 25, 1973, the album was released. Initial sales were comparatively slow. It reached a high of No 7 in the UK chart, but truly took off in December when the first minutes of the opening track were used in The Exorcist, the standout horror film of the era and a box-office sensation.

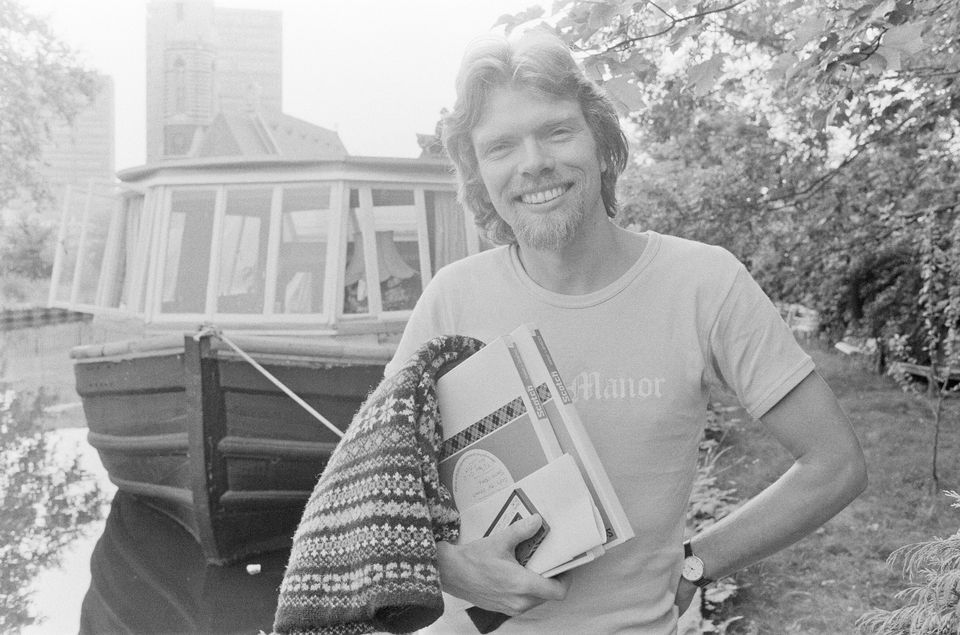

Richard Branson, the 28-year-old mastermind behind Virgin Music in 1979. Photo by Bill Rowntree/Mirrorpix/Getty Images — © Getty Images

Serendipity played its part. Branson had sought a US distribution partner and found it in Atlantic Records. It was during a meeting with that label’s legendary founder, Ahmet Ertegun, that Exorcist director William Friedkin first heard the music. According to Friedkin, the album was a white-label release bearing no artist information, and he simply put on the album, heard the opening bars and decided that it was perfect for his film.

Oldfield was initially unhappy with the motif’s inclusion, but changed his tune when he saw how the association was causing a massive surge in sales. Without his knowledge, Atlantic released a single featuring the piece with the subtitle ‘Now the Original Theme from The Exorcist’. Oldfield refused permission for it to be released in the UK, instead supervising his own edit of the ‘Part II’ suite and putting it out as ‘Mike Oldfield’s Single’.

Tubular Bells is, by an enormous margin, Oldfield’s best-selling album. There were 25 studio albums after that, including four Tubular Bells sequels, one of them a 2003 rerecording of the original. None came close to his debut’s cultural impact. Earlier this year, he announced that he had retired from making new music. His last album, Return to Ommadawn, was released in 2017 and is a sequel to his 1975 album Ommadawn. The word is derived from amadán, the Irish for idiot.

That final album was released on Virgin, but Oldfield’s relationship with Branson has had its ups and downs over the years. The 1990 album Amarok includes an ‘Easter egg’ directed at the entrepreneur. Forty-eight minutes in, Oldfield’s guitar delivers a piece of morse code, which spells out ‘F**k off, RB.’

Oldfield had become irritated by what he felt was a failure by Virgin and Branson to promote his music in the 1980s.

Branson seems not to have minded. One of the perks that Oldfield has enjoyed since Virgin Atlantic was founded in 1984 is complimentary first-class flights on the airline, and that apparently continues to this day.