By Avik Chattopadhyay

Apart from being the International Labour Day, May 1 also happens to be the birthday of personalities like Balraj Sahni, Gordon Greenidge and Joseph Heller. And the Maruti Suzuki Zen.

Apart from being the International Labour Day, May 1 also happens to be the birthday of personalities like Balraj Sahni, Gordon Greenidge and Joseph Heller. And the Maruti Suzuki Zen.

It was launched on that date 30 years ago, at the Maurya Sheraton hotel in New Delhi. Unveiled by then Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee, the Zen went on to become one of India’s most loved brands. Codenamed ‘YE-2’, the little car was a big gamble that both Maruti and Suzuki played in the early 1990s as a new vehicle made for a new ‘liberalised’ India. For those of us who remember, 1991 is when we entered the third phase of our nationhood, the first being Independence in 1947 and the second being the emergency of 1975. This was a new India, wanting to open up to the world and dismantling the red-tapes and licence-controls that defined us in the first four decades of our development.

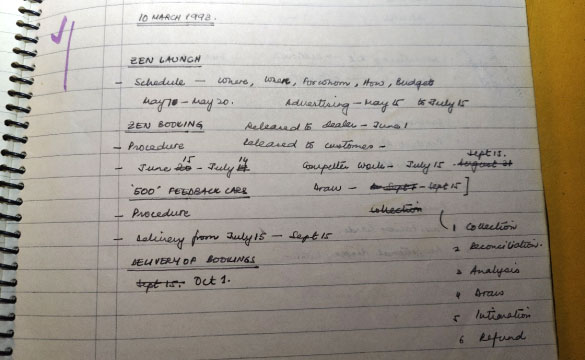

Page from my notebook with notes on the Zen launch plan, dated 10 March 1993.

The Zen defied convention. It was almost the same size as the popular Maruti 800 yet was a very different personality, beyond mere mechanical specifications. While it did have an aluminium engine as a novelty and major talking point, it did not rationally justify the price difference it commended over its older sibling. Till then, a product had to be physically larger than the other to command a higher price. The more the metal, the more the price. That was the only way to demonstrate greater value. Not with the Zen. It demonstrated that aspects like design, touch-and-feel, refinement, dynamic performance and comfort were, in combination, a higher value proposition than competition, even from your own family.

Till 2006, the brand was built as a combination of some clever communication and lots of positive word-of-mouth. In fact, when launched in 1991, it took time to gain public liking. The Indian customer was used to the metal-price equation and the Zen was challenging that. The early adopters did the task of building the initial buzz around its performance and refinement that crucially helped in its gradual adoption and popularity. The initial seven / eight months were an actual struggle. While the network was given lots of “selling tools”, the value proposition was built only when the initial customers swore by it and the automobile journalists praised it sky high. I call this the “Sholay Effect” of hugely successful brands taking time to gain momentum from being almost written off, just like Sholay did.

Magazine covers on the Zen in May-June 1993 – courtesy Team BHP

There were four elements in the way the vehicle was launched which together helped build its formidable equity. First was the Suzuki badge on the vehicle. It was the first Maruti product to carry it, subtly stating that this was an ‘international’ product in the Maruti portfolio. There was a move to have the Maruti badge on the vehicle, but that was dropped in favour of the international narrative.

Second was a term coined to describe its styling – ‘jellybean’. That was the best way to explain its harmonious lines, soft curves and aerodynamic shape, from the front bumper to the rear lights. That term caught the fancy of the media and it was all about jellybean styling after that.

Third was the ultra-smooth all-aluminium engine which was so refined for its time that many, including Wikipedia, think the name Zen stands for ‘Zero Engine Noise’.

Which brings us to the fourth element…the name Zen. It was given by me, in a competition within the company. The then director of marketing and sales Kozo Senga liked the name Zen. I explained that the vehicle was exactly as a Zen monk – you have the power within your outer calm that should be used responsibly and only when required. The vehicle looked sedate when parked but was a rocket when revved. Zen it was!

Rare pic of a YE-2 with the Maruti badge in the plant – taken in Jan 1993

The initial advertising for the Zen did not work. Though all the still photography was done by the amazing Hardev Singh, the advertising agency and the marketing team went overboard with the positioning statement of “Engineered for Exhilaration”. Nobody could either pronounce it properly or remember the statement. Thankfully, the word-of-mouth had started working its magic so the advertising really did not matter. The brochure however was a very popular item and almost all walk-ins into Maruti showrooms wanted one. It was a distinct square shape and the product in all its glory was the hero. Hardev Singh’s photography did the trick. People basically wanted a test drive and a brochure. Heady times indeed!

Zen launch brochure of 1993 and one of 1996

In 1994, the Zen started being exported to various countries, especially those in Europe. Badged as the Suzuki Alto, it was on the streets of London, Paris, Berlin and Rome. This made it the ‘world car’ for Maruti and India and that is what the next communication campaign was all about. This really worked in further building the brand’s appeal as the Indian was now driving exactly what a Londoner or Parisian was.

By now, the sales numbers and growing popularity allowed the engineers in Gurugram to plan modifications and variants. A diesel Zen was launched in 1998 housing a Peugeot engine. Though it did not do very well, it demonstrated the company’s and brand’s engineering prowess as a trend setter. In 1999 a variant called the Zen Classic was launched but did not go well with the Indian design sensibilities. The reversals did not hold the company back from trying yet new things to cater to the Zen-clan.

In 2000, Maruti launched the Alto and the WagonR, both hatchbacks catering to the same demographic target segment. In light of newer siblings, the Zen started losing some if its sheen and some crucial intervention was needed from both the product planning and engineering teams. To commemorate the tenth anniversary of the little monk, Maruti Suzuki did possibly its most audacious move of launching a limited edition 2-door Zen, exactly as it was sold in Europe. Out came 300 Zen Carbons in gleaming black and 300 Zen Steels in svelte silver, each vehicle individually numbered and badged. Even though just 600 units, they took the market by storm, being lapped up by both youth into their first jobs as well as retired couples. The brand was back in the reckoning with a very disruptive step. It was a statement that while the Alto and WagonR were selling in Japan, the Zen was being sold in Europe.

The Zen Carbon and Zen Steel welcome letter – 2003

Closely following the Zen ‘singles’ as they were called was a major restyling of the vehicle to give it a steroid boost. It did create some flutter primarily due to a high-decibel marketing campaign but the vehicle was on its old tired wheels. It had its best chance when Suzuki was planning its next big global launch in India codenamed the YN-4 in 2005. This vehicle would again disrupt the market in the way it looked and performed, just like the YE-2 had done 12 years ago. This should be the new Zen. That is the only way the legend could be revived in its new avatar. An attempt was made in the top circles to carry the Zen badge forward through this new vehicle. Consensus was otherwise. The new vehicle became the Swift, yet another uber successful brand till today.

And the Zen? Well, a half-hearted attempt was made by slapping the name on a car that was a completely different personality from the Zen. It was called the Zen Estilo and launched in 2006. Thankfully the customers saw through the feeble game quicker than Maruti Suzuki had anticipated and the product sank without a trace in 2009. Thereby laying to rest one of India’s most loved and aspired for automotive brands, ever.

Best wishes of the day, little monk.

Rest easy!