How To Find Quality Companies With Consistent Profits And Dividends

Summary

- In this post, I'll begin to explain the process I use to uncover quality dividend stocks, which starts with a review of their dividend and profit track records.

- Most dividend stocks pay at least two dividends each year, so I am willing to accept the occasional missed interim or final dividend, but there must be at least one dividend paid in every one of the last ten years.

- In terms of the ten-year coverage ratio, Unilever earned a total of €60.5 billion and paid a total of €55.6 billion to shareholders through dividends and buybacks.

tadamichi

This is the second in a series of blog posts where I take a detailed look at how I’m investing in quality dividend stocks for long-term income and growth.

In the previous post, I looked at the pros and cons of savings accounts versus dividend stocks for building and generating a retirement income.

In this post, I'll begin to explain the process I use to uncover quality dividend stocks, which starts with a review of their dividend and profit track records.

A long and consistent history of dividends

Before we begin, dividend investing inevitably involves a small amount of financial jargon, so here are a few definitions covering the most important financial lingo used in this post:

- Revenue - This is the total amount of income earned during a year, primarily from the provision of goods and services to customers. Revenue is also known as turnover or “the top line”, because it’s recorded at the top of the income statement (also known as the profit & loss statement or P&L)

- Earnings - This is what’s left over from revenues after deducting all expenses incurred in the production of those revenues. Earnings are also known as profit or “the bottom line”, because they’re recorded at the bottom of the income statement

- Dividend - This is a cash payment that companies make to their shareholders. Dividends are paid out of surplus earnings that the company cannot put to good use internally and they are recorded on the income statement and the cash flow statement

- Share buyback - This is effectively a terminal or final dividend that some companies pay to some of their shareholders in exchange for some of their shares. Remaining shareholders benefit as they still hold the same number of shares, but the total number of shares has reduced, so their proportional ownership of the company has increased. Buybacks are recorded on the cash flow statement

The income statement and cash flow statement mentioned above are two of the three mandatory financial statements that companies have to produce each year. The third is the statement of financial position, or balance sheet, which is where companies record their assets and liabilities.

If you're not familiar with these, here’s a concise UK-centric overview: UK Financial Statements Overview.

Turning back to the task of uncovering quality dividend stocks, I like to get the ball rolling with a few simple checks on a company's dividend history and the earnings upon which those dividends depend.

More specifically, I apply the first of many rules of thumb that make up my dividend investing checklist:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it paid a dividend in every one of the last ten years

Most dividend stocks pay at least two dividends each year, so I am willing to accept the occasional missed interim or final dividend, but there must be at least one dividend paid in every one of the last ten years.

If a company failed to pay any sort of dividend in one of the last ten years, I immediately put it onto my Blacklist, which is a list of stocks I don’t want to invest in.

Having said that, my rules are rules of thumb because I want them to be flexible enough to bend where appropriate and, currently, I think bending this rule is appropriate.

We have, after all, just been through a pandemic, where many high-quality companies suspended their dividends in 2020 or 2021 because large parts of the global economy were closed for months on end.

I don’t want to exclude a high-quality company just because it (perhaps prudently) chose to hoard cash during a pandemic rather than pay out a dividend. So, I am currently making an exception to this rule.

The exception is that I may invest in a company even if it paid no dividend in 2020 or 2021, but if it missed two years of dividends then it will still be excluded.

Finding ten years of financial data

To review a company’s dividend record over ten years we obviously need ten years of data, and my go-to source for financial data is SharePad, a well-known and well-regarded tool for individual investors.

If you don’t want to pay for data, you can find financial results for UK companies on their corporate websites, or through websites such as investegate.co.uk and Companies House.

You can also find summary information (such as a company’s growth rate, growth quality and much more) for hundreds of FTSE All-Share companies in my monthly newsletter.

A long and consistent history of profit

Of course, dividends don’t appear out of thin air. Before a company can pay a dividend, it has to make a profit, and before a company can make a profit, it has to generate revenues.

So, after dividends, the next thing I look for is a long and consistent history of profits and, as with dividends, I have a rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it made a profit in every one of the last ten years

This rule is also flexible because even the best companies sometimes run into short-term problems. But if a company does record a loss, there has to be a very good reason and it should be a very rare event (more than one loss in a decade is almost always enough reason for a company to join my Blacklist).

Profits that consistently cover dividends and fund growth

As I'm fond of saying, you can think of companies as being somewhat like a special type of savings account.

You put money into a savings account, it pays interest, and you can withdraw some or all of that interest or reinvest some or all of it back into the account to help it grow.

The same is broadly true of companies. Shareholders put money into a company and management uses that money to buy productive assets like shops, machinery and goods to sell. The company then (hopefully) makes a profit, and management either pays out some or all of that profit as dividends, or reinvests some or all of it back into the business to help it grow.

Because I’m after income and growth, I want the companies I invest in to generate profits that are large enough to easily cover the dividend while allowing management to retain sufficient earnings to fund inflation-beating growth.

We can measure the gap between earnings and dividends by looking at the ratio between them, which is known as the dividend cover ratio. For example, if a stock has earnings per share (EPS) of £2 and dividends per share (DPS) of £1, its dividend cover is 2.

In fact, a dividend cover of two times is generally thought of as a good safe level, but in my experience, the appropriate level of dividend cover is very company specific. However, at a bare minimum, I do want the dividend to be covered, so I use another rule.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its total earnings over the last ten years exceeded its total dividends and share buybacks

I include share buybacks in my "dividend cover" rule because buybacks are effectively a type of terminal dividend, so earnings need to cover both.

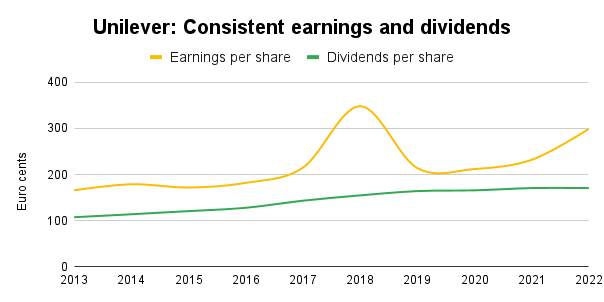

Example: Unilever’s consistent profits and dividends

To bring all of this to life, I'll apply these rules to Unilever (UL) as it’s a popular stock for dividend investors and it is currently a holding in the UK Dividend Stocks Portfolio and my personal portfolio.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it paid a dividend in every one of the last ten years

Unilever sails through this test, with no missed dividends in the last ten years. In fact, Unilever pays four dividends each year, which is very handy for smoothing out your dividend income, and it didn’t miss (or even cut) any of those payments during the pandemic.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if it made a profit in every one of the last ten years

Once again, Unilever passes this test easily, with its earnings per share being nowhere near zero at any point in the last ten years.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its total earnings covered its total dividends and share buybacks over the last ten years

Last but not least, Unilever’s earnings have consistently covered its dividend, in each individual year as well as the last ten years as a whole.

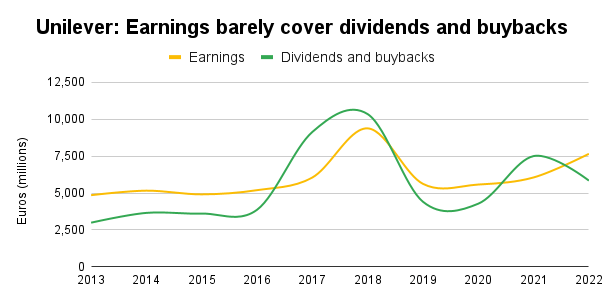

However, my rule explicitly mentions share buybacks, so here’s another chart showing the relationship between Unilever's earnings and both its dividends and buybacks over the last decade.

With buybacks included, we can see that Unilever's earnings have failed to cover its combined dividends and buybacks on several occasions over the last decade.

In terms of the ten-year coverage ratio, Unilever earned a total of €60.5 billion and paid a total of €55.6 billion to shareholders through dividends and buybacks, so despite not fully covering dividends and buybacks in every year, Unilever’s earnings did cover its dividends and buybacks over the decade as a whole.

However, the ten-year coverage ratio was just 1.1, which is slim. This is something I would want to take a closer look at before investing, but for now, I will just say that Unilever does pass this opening salvo of tests.

Editor's Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Editor's Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.