- News

- India News

- ‘Genuine team effort needed to take numbers to 5,000’

Trending Topics

‘Genuine team effort needed to take numbers to 5,000’

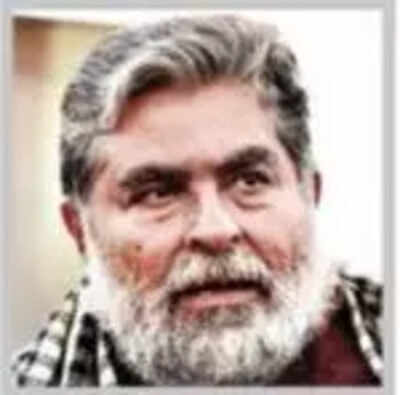

Outspoken writer, conservationist and tiger watcher Valmik Thapar has closely followed the fortunes of Project Tiger nearly since its inception. He has served on the Tiger Task Force set up by the Centre in 2005 and set up an NGO, Ranthambore Foundation, in the 1980s to integrate locals with the cause of protecting the tiger and its ecosystem. In an interview with TOI, Thapar lays out his vision for meeting the challenges of tiger conservation in the coming decade.

Looking back at the 50 years of Project Tiger, what would you say have been its key achievements and the areas where it could’ve done better?

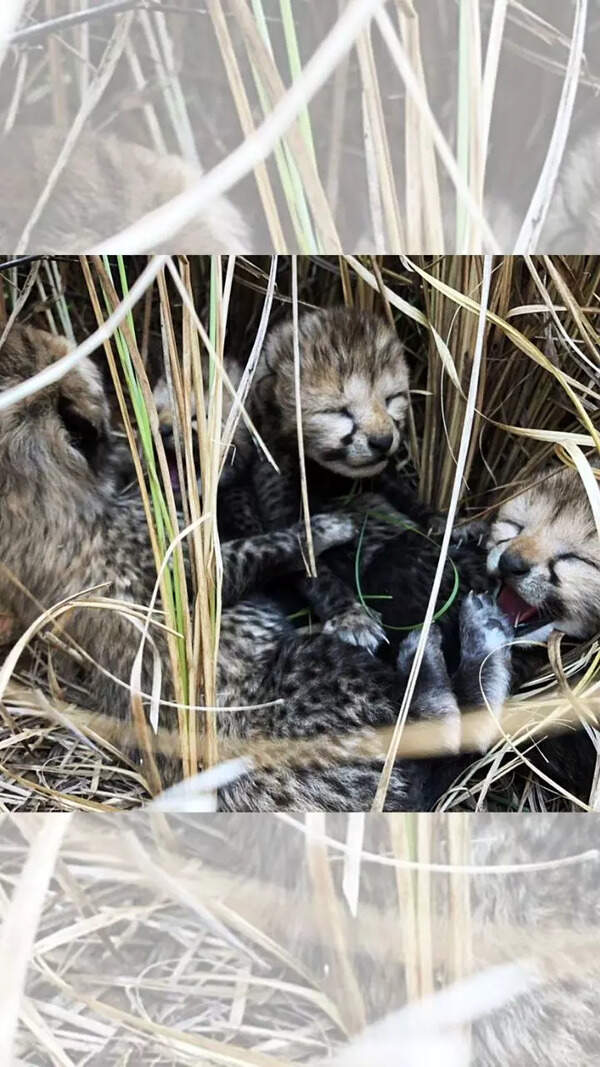

After watching tigers for 48 years, I believe the biggest achievement of Project Tiger is that we still have 2,500 to 3,000 tigers even when our country’s population is touching nearly 1. 4 billion. When Project Tiger started in 1973, we had nine tiger reserves; today, we have 53. Who do we thank? Innovative chief ministers, insightful government servants, good forest officers, and more importantly, independent experts, scientists and so many nameless locals who made a difference. But the most vital players were the thousands of forest guards that protect these wild frontiers and the dozens that sacrificed their lives to defend these against armed poaching and wood-smuggling gangs. They are the true heroes of 50 years of Project Tiger. Could we have done better? Yes, no question about that.

Do we need a different approach to deal with the challenges of protecting India’s tigers in the coming decade?

I believe that to do better in the next decade, the following suggestions need to become policy. This is my five-point plan:

1 The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) must be chaired by an independent expert in tiger conservation. All members must have credible experience. The government staff must do a three month course in tiger management in the wild before joining NTCA, including travel to at least 15 tiger reserves. This will lead to strategic and innovative policy making. The NTCA cannot become the cheetah introduction authority and must stick to tiger conservation.

2 The field directors of all our tiger reserves must have independent experts of that region contracted to work in areas like man-animal conflict, wildlife science and anti-poaching. Contracts can be from three to five years. These independent experts will strengthen field management and ensure efficient field work between forest officers, experts and locals.

3 Village wildlife volunteers need to be engaged in the periphery of our tiger reserves for better protection and monitoring. Working in an honest manner with local communities is the only inclusive way to move to a better future. These volunteers can form the most vital conservation chain across a tiger reserve.

4 We need to identify large tracts of land adjacent to tiger reserves where rewilding is promoted and supported by local governments. This is essential for increasing tiger populations. These lands will be rewilded after a dialogue with village panchayats, village land holders and any other government departments that might own land. These areas could become hubs for engaging wildlife tourism and bird watching. Both will generate revenue for locals. NTCA policy and budget must include this strategy and the first five years will need much hand-holding and financial support. These are the challenges ahead for improving tiger conservation

5 There must be a huge priority in all states for better training and refresher courses for all levels of field forest staff. This will lead to stronger field management.

We need a fresh outlook where instead of pointing fingers there is a genuine team approach and shared decision-making with stake holders and experts. Only then will there be real progress.

When Project Tiger was launched, India’s tiger population was estimated at just over 1,800. It now stands at just under 3,000, as per the 2018 census. What, according to you, would be an optimal population range of tigers in the country?

I believe that the coming decade should be based on innovative suggestions for better governance. We need to rigorously follow best practices. We need reform in our bureaucratic approaches. If we can do this, we could in 10 years set our target on 5,000 tigers. And with a genuine team effort it might even happen.

You closely followed the life of Machhli, the celebrated Ranthambore tigress. It’s now seven years since Machhli died. How would you describe your relationship with this tigress?

I had known Machhli all through her life in Ranthambore. Today nearly 70% of Ranthambore’s wild tiger population draws some link or the other to Machhli. Some of her offspring have gone to Sariska Tiger Reserve, and her grandchildren to Mukundra Tiger Reserve where they have bred and created more ‘Machhlis’. Her remarkable reach has swept across Rajasthan and she will be a tigress that will always be remembered. I am trying to put together a team of people to write a book on her and her legacy.

Looking back at the 50 years of Project Tiger, what would you say have been its key achievements and the areas where it could’ve done better?

After watching tigers for 48 years, I believe the biggest achievement of Project Tiger is that we still have 2,500 to 3,000 tigers even when our country’s population is touching nearly 1. 4 billion. When Project Tiger started in 1973, we had nine tiger reserves; today, we have 53. Who do we thank? Innovative chief ministers, insightful government servants, good forest officers, and more importantly, independent experts, scientists and so many nameless locals who made a difference. But the most vital players were the thousands of forest guards that protect these wild frontiers and the dozens that sacrificed their lives to defend these against armed poaching and wood-smuggling gangs. They are the true heroes of 50 years of Project Tiger. Could we have done better? Yes, no question about that.

Do we need a different approach to deal with the challenges of protecting India’s tigers in the coming decade?

I believe that to do better in the next decade, the following suggestions need to become policy. This is my five-point plan:

1 The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) must be chaired by an independent expert in tiger conservation. All members must have credible experience. The government staff must do a three month course in tiger management in the wild before joining NTCA, including travel to at least 15 tiger reserves. This will lead to strategic and innovative policy making. The NTCA cannot become the cheetah introduction authority and must stick to tiger conservation.

2 The field directors of all our tiger reserves must have independent experts of that region contracted to work in areas like man-animal conflict, wildlife science and anti-poaching. Contracts can be from three to five years. These independent experts will strengthen field management and ensure efficient field work between forest officers, experts and locals.

3 Village wildlife volunteers need to be engaged in the periphery of our tiger reserves for better protection and monitoring. Working in an honest manner with local communities is the only inclusive way to move to a better future. These volunteers can form the most vital conservation chain across a tiger reserve.

4 We need to identify large tracts of land adjacent to tiger reserves where rewilding is promoted and supported by local governments. This is essential for increasing tiger populations. These lands will be rewilded after a dialogue with village panchayats, village land holders and any other government departments that might own land. These areas could become hubs for engaging wildlife tourism and bird watching. Both will generate revenue for locals. NTCA policy and budget must include this strategy and the first five years will need much hand-holding and financial support. These are the challenges ahead for improving tiger conservation

5 There must be a huge priority in all states for better training and refresher courses for all levels of field forest staff. This will lead to stronger field management.

We need a fresh outlook where instead of pointing fingers there is a genuine team approach and shared decision-making with stake holders and experts. Only then will there be real progress.

When Project Tiger was launched, India’s tiger population was estimated at just over 1,800. It now stands at just under 3,000, as per the 2018 census. What, according to you, would be an optimal population range of tigers in the country?

I believe that the coming decade should be based on innovative suggestions for better governance. We need to rigorously follow best practices. We need reform in our bureaucratic approaches. If we can do this, we could in 10 years set our target on 5,000 tigers. And with a genuine team effort it might even happen.

You closely followed the life of Machhli, the celebrated Ranthambore tigress. It’s now seven years since Machhli died. How would you describe your relationship with this tigress?

I had known Machhli all through her life in Ranthambore. Today nearly 70% of Ranthambore’s wild tiger population draws some link or the other to Machhli. Some of her offspring have gone to Sariska Tiger Reserve, and her grandchildren to Mukundra Tiger Reserve where they have bred and created more ‘Machhlis’. Her remarkable reach has swept across Rajasthan and she will be a tigress that will always be remembered. I am trying to put together a team of people to write a book on her and her legacy.

Start a Conversation

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

FacebookTwitterInstagramKOO APPYOUTUBE