- News

- India News

- How netas are scoring with football in Manipur

Trending Topics

How netas are scoring with football in Manipur

Late last month, when over 29,000 football faithful turned up for the first international football match hosted by Manipur, against crossborder rivals Myanmar, a tonedeaf Igor Stimac, India’s Croatian chief coach, casually foisted the blame for his team’s lacklustre performance on the “sleeping crowd”.

A few worn-out turfs away though, things were anything but sleepy. In the local and developmental leagues — being played in the same week that the Indian team was stationed in Imphal — women, children and men lustily cheered a fine move, a stunning save or raged against a referee’s ruling. Advice, encouragement, insults and barbs flowed freely as fans and players made their minds known and fierce local rivalries heated up under the afternoon Imphal sun.

At the second India game, Stimac had his wish granted. His plea for “them to sing for 90 minutes in the next game,” was met with a resounding response as locals began to gather from two in the afternoon for a 6pm kick-off against Kyrgyz Republic. The home team would perform a shade better than they did against Myanmar, winning 2-0. The roomy stadium was awash with the waving Tricolour.

The state’s BJP-led government was ecstatic. Calls for more international football matches rent the air and an announcement followed from CM Biren Singh for a 75,000-seater stadium. The CM and Kalyan Chaubey, the All India Football Federation president and a former footballer who’s now a BJP politician from West Bengal, announced an MoU to strengthen footballing infrastructure in the state.

Driving The Discourse

In Manipur, football is a metaphor for many things political and social. The state recognises the influence it can wield. Biren Singh, a former Durand Cupper with the BSF, often invokes football in his speeches, never forgetting to remind the people of his long association with the sport. The untiring rhetoric has begun to wear out the many ex-professional and international footballers.

They concede though that it helps to be seen as part of the state’s political elite against a backdrop of mushrooming football academies in Imphal valley and land being acquired on the state capital’s outskirtsfor such projects.

As part of BJP’s assertion of nationalism through sports, football and Manipur are familiar yet fresh frontiers. Unmissable in the self-congratulatory messages last month was the praise for the state government’s efforts to get India to play in Imphal. “Manipur has hosted an international match for the first time… and our state government has organised the tournament brilliantly today,” tweeted BJP MLA Rajkumar Imo Singh.

“When have you seen so many India flags in Manipur before?” asks Imo, who happens to be Biren’s son-in-law. “I would not have minded had there been a few BJP flags in the crowd as well,” he adds with a chuckle. “What’s wrong if a party or its government is pushing for the promotion of a certain sport?” Imo should know, heading as he does the Manipur Cricket Association, a body widely noticed for its efficient running and sudden infusion of funds and infrastructure. Once a Congress neta, Imo’s controversial departureto BJP last year drew much attention.

Flip-Flops And Deft Moves

The Manipur assembly polls in MarchApril 2022 were seen as the advent of a BJP wave, bringing with it a new political reality that has made defections seem even more acceptable. “This is part of our politics. It’s pretty unique. I was in JD(U). We don’t find support at the Centre. We cannot do anything if we are sitting in the opposition. That’s why the move to BJP,” says Arunkumar, president of I-League club Neroca FC. He contested the last assembly elections on a JD-U ticket, won, and promptly defected to the BJP.

“Why should you bother so much about elected MLAs going party hopping in Manipur?” says Tennoson Pheiray, general secretary of the district football association in the hill district of Ukhrul, “Don’t footballers change jerseys after a match? In Manipur, the MLAs do just that after each election. We don’t pay it much attention. You shouldn’t either. ”

The reasons for the ‘BJP wave’ in Manipur are many. Explains Dr N Bijen Meetei, associate professor in the political science department at Manipur University, “In 2022, the BJP won not only because it is in office at the Centre, butthey were clever enough to address local issues better than other parties. ”

Drifting along or swept away in this wave are the many indigenous communities of Manipur, caught in a constant search for identity. On the north-eastern outskirts of Imphal, off the highway that leads to Ukhrul, is the Muslim-dominated Khetripal area. Local MLA Sheikh Noorul Hassan of the National People’s Party counts among his constituents Manipur’s muslims – Meitei Pangals – whose vote is the deciding factor in as many as 13 assembly seats. NPP is in alliance with BJP but the 36-year-old feels the saffron party’s attitude has been one of “lip service”.

“It is only an illusion. We haven’t seen a cabinet post (despite the alliance). We know it all depends on the BJP central leadership in Delhi, but we have no voice in policy-making. The PM’s slogan of ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas,’ should work in spirit also,” he says. Hassan owns three football clubs, including one women’s team, which he says comprise players from local communities. He also fields a cricket team in the state league.

Laying The Ground

Meetei points to three key issues that Biren Singh has capitalised on. “Introduction of the Inner Line Permit in Manipur, the renaming of Mount Harriet in theAndamans as Mount Manipur to pay tribute to its freedom fighters. But it was the relief work during the pandemic that had the greatest impact. ”

Concurs Lolendro Singh, a former Mohun Bagan captain, “We did a lot of work during Covid in our Leikai area of Imphal. The elected MLA was doing nothing, so we took it upon ourselves to distribute rice, vegetables and medicine. ”

Though he denies being a part of the BJP, the soft-spoken Lolendro is often ribbed by his footballing friends about how he is immersed in party work now. Lolendro’s “we” is a group of family and friends from the locality led by rice contractor Soraisam Gobin. The result of the Covid outreach was that Gobin’s wife Kebi Devi was elected as MLA from the BJP last year. Known to be part of Biren’s inner circle, Kebi Devi’s political rise may have paved the way for the construction of the stunning Chumthang Shannapung sports academy.

“We could obtain agricultural land since it was for a sports academy,” says Lolendro about the space sprawled over four acres near rice fields that surround the airport, its spanking new football turf easily identifiable from the air.

Football is booming in the valley and BJP well understands its national potential. Chaubey and Biren, former footballers both, predictably provide the ideal optics. Such is the focus that Chaubey is okay with being overlooked for a BJP ticket for next year’s general elections. “I will not contest next year. One cannot do both. Football takes up all my attention,” he says. After losing in the last assembly polls in Bengal it was quietly decided by BJP to groom Chaubey for national football politics as the party sought control of most sports administrative bodies in New Delhi.

For BJP leaders visiting Manipur, there is the obligatory stop-over at the Union sports ministry’s ambitious National Sports University, a multi-discipline, multi-crore project coming up on over 325 acres of land made available by the state government in West Imphal district. The foundation stone was laid by PM Narendra Modi in March 2018.

Crying Foul

But many express concern. Sitting in his makeshift office that overlooks the Ukhrul district football ground, Pheiray, a Tankhul, talks about the anxieties of the hill regions of Manipur.

“Despite Biren Singh’s ‘Go To The Hills’ call, we know that the gap between the benefits for the valley and what the hill districts get is increasing. Next on the table is the Meitei demand for ST status. We stand to lose our land if that happens,” he laments. The famed Shirui Lily Cup, Manipur’s second-oldest football tournament played since 1973-74, is grappling with a funds crunch. It is symptomatic of the skewed nature of Manipur’s hill-valley resource divide.

Instead of waiting, some in the hills have begun to make their own path. Reisangmei Vashum, a former Churchill Brothers and East Bengal midfield mainstay is back home, a patron now of the Ukhrul FC academy. Situated on the edge of a hillock outside Ukhrul town, the tiny academy, aided by CSR outreach from the Airports Authority of India, stands as a defiant dream of the Tankhuls, a proud footballing people. “Ours is the only dialect in the region that has a name for football – Kanthai – which every child here learns first,” says Rinshang Pheiray who, like many Tankhuls, seeks a better life in the valley. “Football,” he says, “remains the one main channel for the hills and the valley to communicate. ”

A few worn-out turfs away though, things were anything but sleepy. In the local and developmental leagues — being played in the same week that the Indian team was stationed in Imphal — women, children and men lustily cheered a fine move, a stunning save or raged against a referee’s ruling. Advice, encouragement, insults and barbs flowed freely as fans and players made their minds known and fierce local rivalries heated up under the afternoon Imphal sun.

At the second India game, Stimac had his wish granted. His plea for “them to sing for 90 minutes in the next game,” was met with a resounding response as locals began to gather from two in the afternoon for a 6pm kick-off against Kyrgyz Republic. The home team would perform a shade better than they did against Myanmar, winning 2-0. The roomy stadium was awash with the waving Tricolour.

The state’s BJP-led government was ecstatic. Calls for more international football matches rent the air and an announcement followed from CM Biren Singh for a 75,000-seater stadium. The CM and Kalyan Chaubey, the All India Football Federation president and a former footballer who’s now a BJP politician from West Bengal, announced an MoU to strengthen footballing infrastructure in the state.

Driving The Discourse

In Manipur, football is a metaphor for many things political and social. The state recognises the influence it can wield. Biren Singh, a former Durand Cupper with the BSF, often invokes football in his speeches, never forgetting to remind the people of his long association with the sport. The untiring rhetoric has begun to wear out the many ex-professional and international footballers.

They concede though that it helps to be seen as part of the state’s political elite against a backdrop of mushrooming football academies in Imphal valley and land being acquired on the state capital’s outskirtsfor such projects.

As part of BJP’s assertion of nationalism through sports, football and Manipur are familiar yet fresh frontiers. Unmissable in the self-congratulatory messages last month was the praise for the state government’s efforts to get India to play in Imphal. “Manipur has hosted an international match for the first time… and our state government has organised the tournament brilliantly today,” tweeted BJP MLA Rajkumar Imo Singh.

“When have you seen so many India flags in Manipur before?” asks Imo, who happens to be Biren’s son-in-law. “I would not have minded had there been a few BJP flags in the crowd as well,” he adds with a chuckle. “What’s wrong if a party or its government is pushing for the promotion of a certain sport?” Imo should know, heading as he does the Manipur Cricket Association, a body widely noticed for its efficient running and sudden infusion of funds and infrastructure. Once a Congress neta, Imo’s controversial departureto BJP last year drew much attention.

Flip-Flops And Deft Moves

The Manipur assembly polls in MarchApril 2022 were seen as the advent of a BJP wave, bringing with it a new political reality that has made defections seem even more acceptable. “This is part of our politics. It’s pretty unique. I was in JD(U). We don’t find support at the Centre. We cannot do anything if we are sitting in the opposition. That’s why the move to BJP,” says Arunkumar, president of I-League club Neroca FC. He contested the last assembly elections on a JD-U ticket, won, and promptly defected to the BJP.

“Why should you bother so much about elected MLAs going party hopping in Manipur?” says Tennoson Pheiray, general secretary of the district football association in the hill district of Ukhrul, “Don’t footballers change jerseys after a match? In Manipur, the MLAs do just that after each election. We don’t pay it much attention. You shouldn’t either. ”

The reasons for the ‘BJP wave’ in Manipur are many. Explains Dr N Bijen Meetei, associate professor in the political science department at Manipur University, “In 2022, the BJP won not only because it is in office at the Centre, butthey were clever enough to address local issues better than other parties. ”

Drifting along or swept away in this wave are the many indigenous communities of Manipur, caught in a constant search for identity. On the north-eastern outskirts of Imphal, off the highway that leads to Ukhrul, is the Muslim-dominated Khetripal area. Local MLA Sheikh Noorul Hassan of the National People’s Party counts among his constituents Manipur’s muslims – Meitei Pangals – whose vote is the deciding factor in as many as 13 assembly seats. NPP is in alliance with BJP but the 36-year-old feels the saffron party’s attitude has been one of “lip service”.

“It is only an illusion. We haven’t seen a cabinet post (despite the alliance). We know it all depends on the BJP central leadership in Delhi, but we have no voice in policy-making. The PM’s slogan of ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas,’ should work in spirit also,” he says. Hassan owns three football clubs, including one women’s team, which he says comprise players from local communities. He also fields a cricket team in the state league.

Laying The Ground

Meetei points to three key issues that Biren Singh has capitalised on. “Introduction of the Inner Line Permit in Manipur, the renaming of Mount Harriet in theAndamans as Mount Manipur to pay tribute to its freedom fighters. But it was the relief work during the pandemic that had the greatest impact. ”

Concurs Lolendro Singh, a former Mohun Bagan captain, “We did a lot of work during Covid in our Leikai area of Imphal. The elected MLA was doing nothing, so we took it upon ourselves to distribute rice, vegetables and medicine. ”

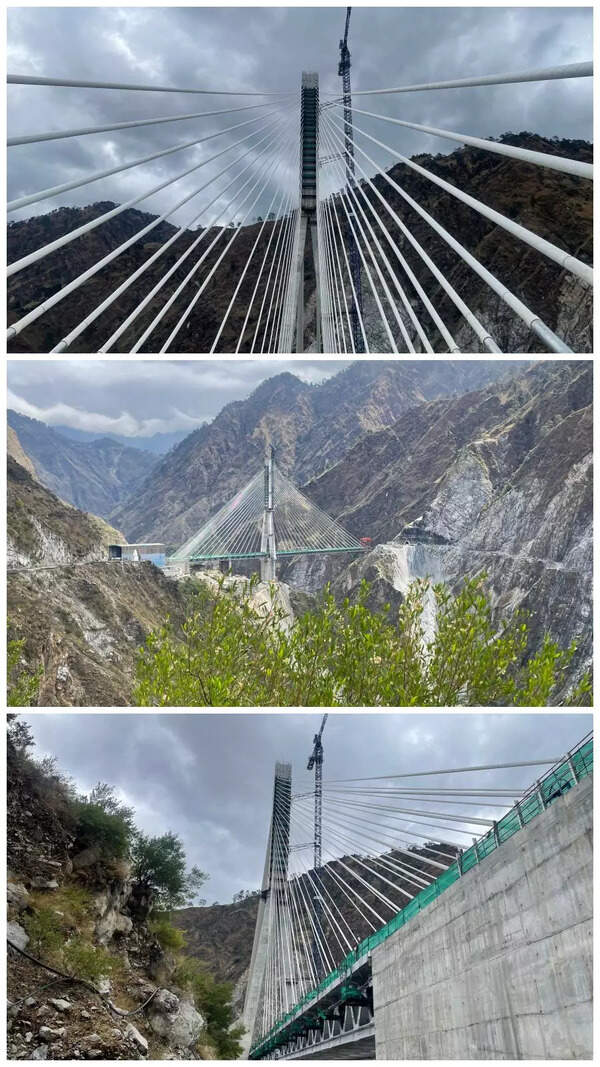

Though he denies being a part of the BJP, the soft-spoken Lolendro is often ribbed by his footballing friends about how he is immersed in party work now. Lolendro’s “we” is a group of family and friends from the locality led by rice contractor Soraisam Gobin. The result of the Covid outreach was that Gobin’s wife Kebi Devi was elected as MLA from the BJP last year. Known to be part of Biren’s inner circle, Kebi Devi’s political rise may have paved the way for the construction of the stunning Chumthang Shannapung sports academy.

“We could obtain agricultural land since it was for a sports academy,” says Lolendro about the space sprawled over four acres near rice fields that surround the airport, its spanking new football turf easily identifiable from the air.

Football is booming in the valley and BJP well understands its national potential. Chaubey and Biren, former footballers both, predictably provide the ideal optics. Such is the focus that Chaubey is okay with being overlooked for a BJP ticket for next year’s general elections. “I will not contest next year. One cannot do both. Football takes up all my attention,” he says. After losing in the last assembly polls in Bengal it was quietly decided by BJP to groom Chaubey for national football politics as the party sought control of most sports administrative bodies in New Delhi.

For BJP leaders visiting Manipur, there is the obligatory stop-over at the Union sports ministry’s ambitious National Sports University, a multi-discipline, multi-crore project coming up on over 325 acres of land made available by the state government in West Imphal district. The foundation stone was laid by PM Narendra Modi in March 2018.

Crying Foul

But many express concern. Sitting in his makeshift office that overlooks the Ukhrul district football ground, Pheiray, a Tankhul, talks about the anxieties of the hill regions of Manipur.

“Despite Biren Singh’s ‘Go To The Hills’ call, we know that the gap between the benefits for the valley and what the hill districts get is increasing. Next on the table is the Meitei demand for ST status. We stand to lose our land if that happens,” he laments. The famed Shirui Lily Cup, Manipur’s second-oldest football tournament played since 1973-74, is grappling with a funds crunch. It is symptomatic of the skewed nature of Manipur’s hill-valley resource divide.

Instead of waiting, some in the hills have begun to make their own path. Reisangmei Vashum, a former Churchill Brothers and East Bengal midfield mainstay is back home, a patron now of the Ukhrul FC academy. Situated on the edge of a hillock outside Ukhrul town, the tiny academy, aided by CSR outreach from the Airports Authority of India, stands as a defiant dream of the Tankhuls, a proud footballing people. “Ours is the only dialect in the region that has a name for football – Kanthai – which every child here learns first,” says Rinshang Pheiray who, like many Tankhuls, seeks a better life in the valley. “Football,” he says, “remains the one main channel for the hills and the valley to communicate. ”

Start a Conversation

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

FacebookTwitterInstagramKOO APPYOUTUBE