Recession Is On: So Says A Very Reliable Indicator, The 10-2 UST Spread

Summary

- The recession "red flag" has been raised. The spread between the 10-year and 2-year US Treasury securities, an indicator with a strong history of accuracy, is rising after crashing.

- What's different about the current situation is just how "inverted" the yield curve became. That could be the wildcard that defeats this nearly undefeated recession indicator.

- But I don't think it will be defeated this time. Recession is coming. But rather than obsess over the R-word, let's figure out how to profit from it.

Melpomenem

The past 16 months have introduced plenty of new investment jargon to investors who were not active investors the last time we had a financial crisis, recession or sustained rise in interest rates. Words and phrases like "Fed pivot," "dot plot," and of course that old classic "inflation, have gone from the history books to the front pages.

Another phrase making a comeback, and perhaps the most important one for investors in bonds and stocks, is "yield spread." In particular the spread, or difference in yield, between the 10-year US Treasury Bond and the 2-year Treasury Note. Here's a picture of its path since the late 1980s, when I was a newbie in the investment business.

I've included those gray shaded areas as well. Those are US recessions. So, now that the chart is there to be seen, here's a quick riddle: what has happened shortly before each of the past four recessions? Answer: The 10-2 spread dropped below zero, then shot back up toward zero and returned to its normal, positive position. I say normal because in the bond market, it makes sense that the longer your money is tied up being lent to the US government or another debtor, the more risk is attached, and the higher the yield/return an investor demands.

A funny thing happened on the way to the recession... OK, not so funny

Investors are typically much more familiar with the workings of the stock market than the bond market. Can you blame them? Bonds have largely been a waste of investor brain space for over a decade, with the Fed and other central banks pursuing "ZIRP: zero interest rate policies" to keep money cheap and easy to borrow. Finally in 2023, we're starting to see that 15 years of easy money means that, eventually, things break. Like certain top-16 US banks. There will likely be more to break as this year goes on, and the only question is whether it will be isolated or systemic. We'll see.

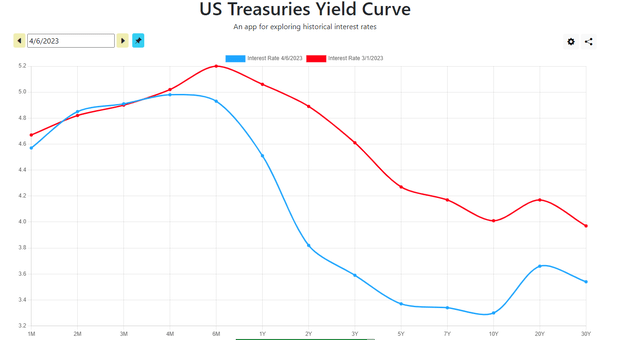

The more immediate concern here is that 10-2 spread. First, it went negative, as T-Bills and other short-term Treasury yield spiked, thanks to a record-fast series of rate hikes by the Fed. Just look at this chart below to see how rapidly the 2-year rate climbed. Sure, the 10-year did so as well, but that move started around 1% 2 years ago. 2-year Treasuries were yielding just above zero for quite some time.

And now, all of a sudden, bonds matter again. They're a lot more investable than many investors have ever known. I suspect that some are still trying to grapple with how to deal with it. More on that later in this article.

The 2-year yield is more driven by the same things that influence T-bill rates (which range from 1 year to maturity and less). 10-year yields are not as directly influenced by the Fed, since that entity only controls very short-term rates. But that longer-term part of the bond market does take plenty of cues from the Fed's activity and words.

The other thing that really influences the 10-year yield is what we call a "flight to safety" scenario, which is what I think is driving that yield lower, and very quickly. Recession talk is not only in the air, but increasingly in economic figures. And, while yields are falling across the board, the 2-year is finally falling faster than the 10-year. Translation: the "inverted yield curve spread" between the 2 is starting to narrow. Here's a picture of it:

Bond yields dropping (ustreasuryyieldcurve.com)

Just look at how quickly rates are dropping across the board. At the start of March, the entire US Treasury curve was briefly above 4% yield. Now, everything from two years to maturity and longer is below 4%. Short-term rates went parabolic in a short period of time, but even those are falling and fast enough so that the 10-2 spread is starting to close in toward zero. It's still a ways from it, but I don't think we should put anything past the bond market these days in terms of how quickly events can change things. As I've noted in other articles recently, the bond market is moving around like it thinks it's the stock market. Lots of volatility. And with the storm clouds of recession building, it appears the move toward zero in the 10-2 spread is in motion.

To clarify, while investors may be used to hearing things like "inverted yield curves lead to recessions," that's only partially accurate, based on the history pictured above. It's not the inversion (2-year rate above 10-year rate) that coincides with recession. That's like football's two-minute warning. It's the eventual unwinding of that inversion, where the 10-year US Treasury rate resumes its normal position at a higher yield than the 2-year US Treasury, that's closely in sync with the start of a recession.

Do we believe the 10-2 spread this time? I do. I think there are just too many other signs of recession looming. From the long list of those I track and consider to be important, here are two more. Below you see that spreads on the highest rated level of junk bonds (BB) are near a 2-year peak, signaling that risk is finally starting to be recognized in that market. The bottom part of the chart is the US Index of Consumer Sentiment, which has been tumbling for about two years, and in retrospect, was as good an indicator that 2022 would be a tough investing year as any I follow. And, it continues to stay low. That's another recession signal to me.

Still the actual declaration of a "recession" is not the big event. As always, what labels we investors assign to things is not what matters. All that matters is what happens to the prices of the securities you own, when you own them. So, here are a few ideas about how to try to profit from a recession period, or just conditions that remind us of recessions. After all, history shows us that by the time a recession is officially declared, most of the market damage may already be done. So I suggest focusing on the buys, sells, and holds in portfolios, not on the headlines about the timing of a recession. This will be a review of some things I've discussed in other recent strategy articles, since fortunately, my views on handling these difficult markets in 2023 don't change daily or weekly.

First, recognize that a continued decline in bond yields offers significant opportunity to "win" both ways: You get some yield as well as price appreciation. But when I say that bonds look good, I'm strictly limiting my enthusiasm to US Treasuries, either bought directly, or through ETFs I've recommended in other articles. One very recent opinion was a buy rating on Cambria Tail Risk ETF (TAIL), which combines 10-year US Treasuries and S&P 500 put options for an eclectic but useful mix in recessions.

Short-term bonds still work. I wrote about iShares Short Treasury Bond ETF (SHV) a while back, and still believe it represents what's left of the "sweet spot" of the Treasury yield curve. I would like to offer some positive opinions on the "credit" bond ETFs I follow, but I'm just not there yet. I still see things setting up for a credit crisis of some sort this year. We never know where those will come from, but we do know that US Treasuries are not likely to be caught up in it. That is unless Congress screws up the debt ceiling debate. But that's beyond the scope of this article.

In equities, the key is not so much what you own, but how you own it. In other words, "renting" ETFs that target a market segment, and knowing the upward move, if any, won't likely last beyond weeks or a few months, before the recession fears and inflation fears knock them down.

I'll be covering these subjects plenty more in the days ahead. In summary, a recession is probably coming, but the more important factor for investors is that the fear of recession is creeping in as spring does. That's ultimately what moves prices of stocks and bonds, and thus, we have to make recession-era investing front and center in our investment strategy for the foreseeable future.

This article was written by

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of SHV, TAIL either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

I also own a small position in IEF, an ETF that owns 7-10 year US Treasury securities

Seeking Alpha's Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.