This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

At 9:45 a.m. on October 11, 1944, WWII 1st Lieutenant Victor Phelps bailed out of his P47D-Thunderbolt airplane - the “Nittany Nipper”- after being shot down by German forces while on a mission to destroy a railroad bridge over the Senio River near Imola, Italy.

The river coursed along what was known as the Gothic Line, which Phelps and other members of the Twelfth Air Force’s 87th Fighter Group were attempting to disrupt in their mission to liberate Italy from German control.

Joel Farr, Phelps’ grandson, obtained information about Phelps’ service and crash from the National Archives of the United States, which included a missing air crew report submitted on October 13, 1944.

The information was scant. It provided coordinates of Phelps’ mission target, departure place and time, a box marked "yes" next to the line "parachutes were used."

The last article of the report requested a description of the search, if any, and to provide the name, rank and serial number of the officer in charge.

Atop the blank line that followed Article 15 were three words – “No search made.”

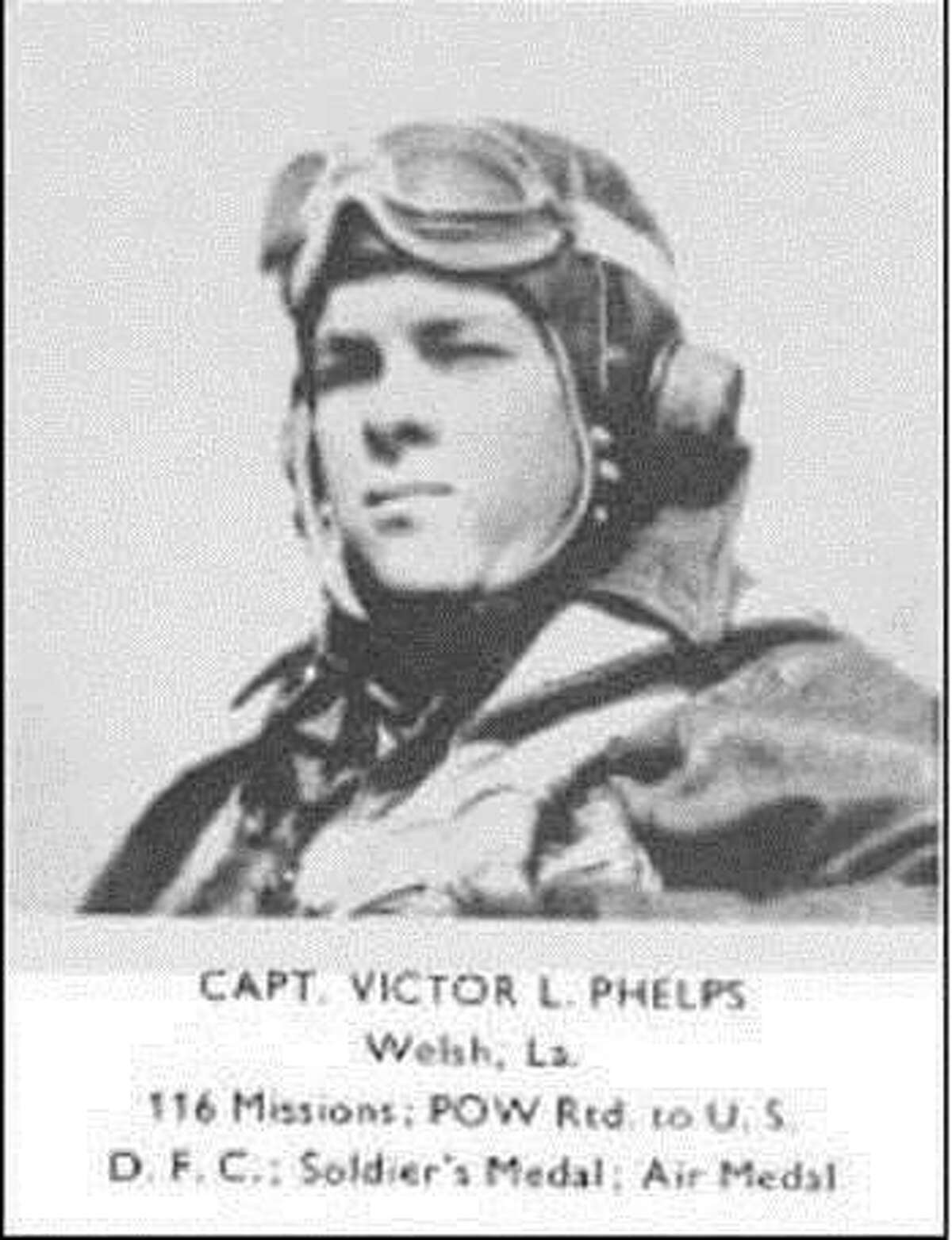

Phelps didn’t like to talk about the war, though he’d flown 116 missions and had numerous commendations, including one for rescuing a fellow pilot from a burning plane after returning from fighting on the D-Day Invasion.

Victor Phelps especially didn’t like to talk about what happened after his plane crashed on the Gothic Line outside a small town in northern Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region.

“Everything I know I had to pull out of him,” said (Norma) Sue Phelps Stephenson, who met Phelps at Louisiana State University in 1947 and married him a year later.

Among the details Stephenson passed on to Farr and other family members was that as Phelps parachuted down, he could see German soldiers with guns on one side of him and Italian villagers with pitchforks on the other.

“He said, ‘I hope the guns get me first,’” recounted Farr.

For years, it was one of the few bits of first-hand information he had about his grandfather’s war-time experience.

Phelps hid in a farm near Imola for several days after the crash but was eventually captured by German troops, who took him as a prisoner of war. Phelps was first held captive in a pig stall, then moved to a camp in Poland – Stalag 3 – the same camp memorialized in the 1963 film “The Great Escape.”

Throughout the months of his imprisonment, Phelps endured one of the war’s infamous “death marches,” wherein prisoners were forced to walk from one prison camp to the next. Many did not survive the trip, and Farr said his grandfather was carried by fellow prisoners on a blanket to prevent him being killed, as prisoners who could no longer walk were simply shot and left for dead.

One of the few details Stephens knows about her husband’s POW experience is that he knew about the escape tunnel that was reportedly being built at Stalag 3.

“He knew, but he didn’t want to know,” she said. Too much knowledge could be a dangerous thing.

On April 29, 1945, American troops led by Gen. George Patton liberated Phelps and others from Stalag 3.

Phelps came home.

He met his wife Sue at a community dance. She was a classic story of “sweet 16 and never been kissed, because all the boys had gone to war,” she said.

Stephenson was supposed to be the date of a college classmate, but one look at his friend – Phelps, who pulled up in a dark blue Ford convertible – and she said, “I want him.”

A year later, they married.

Phelps got a job at Chevron Phillips in Orange, and Southeast Texas became their new home. Sue became a teacher in Buna schools.

They started a family that grew to include six children, two girls and four boys.

The Phelpses lived life as most veterans did after the war -- in a whole new normal.

Stephenson mourned Phelps’ passing in 1976 but continued to honor his memory along with her children and grandchildren, including Joel Farr.

Every Veteran’s Day, Farr, a self-proclaimed history buff, would honor his family members’ service with a post. It would include a testament to both of his WWII veteran grandfathers – Victor Phelps and Leslie Farr, who served in a light tank battalion and fought many battles.

Shortly after Farr’s 2018 Veteran’s Day post, he received a strange message.

“Hi Joel from Italy,” the Facebook message said.

It went on to inquire about Farr’s relationship to Victor Phelps.

“I live near Imola and near the place where Victor L. Phelps crashed on 11 October 1944. Perhaps is your grandfather? Saturday we will remember the event and also Victor during an excursion to that place.”

Farr feared the message was an online scam, but his interest was piqued.

“Yes Victor was my grandfather. Why will you be remembering him?” Farr replied.

The messenger – Andrea Soglia – replied with information gathered firsthand by villagers in his hometown, including photographs of his grandfather’s plane crashed on the ground, surrounded by villagers.

Among them was a young Arturo Frontali, who at the time of Farr and Soglia’s contact was still alive and taking part in a liberation day remembrance ceremony that included honors to Victor Phelps and the plane crash that was part of their village’s Nazi liberation story.

Frontali was just a teen when Phelps’ plane crashed and has been a staple at the region’s annual celebrations, recounting what he and his twin sister witnessed of Phelps’ crash, a story he’d like to share with Phelps’ family in person.

That meeting will come soon, as the family has garnered support for a trip to Imola, where they will gather with villagers honoring Phelps on April 29, 2023, for the next Liberation Day celebration.

It’s a wish that’s been years in the making, as the family wanted to venture overseas after first learning of the event.

“I would love to travel and come see all of this,” Farr wrote to Soglia in their early correspondences.

He also wanted his mother to go, and any other family members that could make the trip to witness the celebratory honors. But most of all, he wanted his grandmother – (Norma) Sue Phelps Stephenson -- to see how her husband’s memory has been honored decades after the war’s end.

Then COVID-19 hit, and travel complications including locating birth certificates needed for passports, delayed their visit to the place that has honored Victor Phelps in the way they’d longed to see him honored for decades.

Last year, Farr learned that a plaque in Phelps’ honor had been installed for the 2022 festivities.

It was the final straw in pushing the family’s decision to make their move for a trip to Italy.

Eldest grandson Marc Phelps – the only grandchild who knew Victor before his passing - reached out to Twilight Make A Wish Foundation after seeing an advertisement online.

The organization helps make dreams come true for senior citizens.

Often the dreams are small – help paying bills, taking a trip to meet a new young relative, crossing a long-imagined dream off their bucket list, like petting a penguin, or seeing their last major league baseball game in person.

But sending a WWII veterans’ family to Italy to experience the memorial in his honor on Liberation Day? That was wish fulfillment on a whole new level.

The Philadelphia-based hub responded with enthusiasm, passing along the project to their new Houston chapter, which started last year.

Chapter founder Bill Graff and his team not only had their first wish to make come true, they had a one-of-a-kind wish to make come true, which ultimately would be come the national foundation's 5,000th wish to grant since its start in 2003.

It was like hitting a home-run their first time at bat.

“This (WWII) generation is going away, so this kind of wish is going to be rarer and rarer,” Graff said.

Of the few remaining, many will likely pass before their dreams can be fulfilled.

That won’t be the case for Victor Phelps’ family.

Graff and his team tackled the project with gusto, jumping in on fundraising efforts with online campaigns and live events at local establishments, like that which took place earlier this month at Giannina’s Pizza in Cypress, near Stephenson's nearby retirement home.

The sold out guest list got extra traction from diners, who simply happened to be there when the event got underway – couples who offered a cash donation as the event unfolded.

Others, like Gay Garrett from Brookdale Senior Living, registered for the food and wine tasting to support the Houston Twilight Make A Wish chapter’s mission. “I love the idea of this organization,” she said, adding that the Make A Wish Foundation is the charity adopted by her alumni sorority Chi Omega.

The group filled the adjoined tables running the length of the small pizzeria, raising glass after glass of Italian wine and sharing the many pizza varieties emerging from the restaurant’s brick oven throughout the event.

“Food is life,” said restaurant co-owner Giannina Cicciarella, who runs the establishment with parents Salvatore and Francesca, natives of Sicily.

A map of Italy, broken down by states, is painted on a wall near the restaurant entry.

Salvatore talked with Stephenson, pointing out the region where she and family would visit next month.

It’s an area north of his coastal homeland – a place renowned for its creation of the “dish of Italy” – commonly known as spaghetti Bolognese, as well as birthplace of the famed Ferrari family.

Amid the revelry, Farr said he’d already gotten messages from his Italian contacts asking about what foods they’d like to eat.

While Soglia and others are eager to present the best their region has to offer now, they’re more excited to show them the best their region has to remember from its past.

It’s a history steeped in valiant efforts from liberation fighters at home and abroad.

It’s the efforts of people like 1st Lt. Victor L. Phelps.

“Really, it’s a miracle that man in Italy saw that post Joel put up. It’s so amazing. Joel is online in a little town in East Texas – Buna – and hears from this man in Italy,” Stephenson said. “I always felt like Vic had not been honored enough, but he got the recognition in Italy that he never got in America.”

And now, for the first time, his wife, daughter, son and grandson will witness firsthand how villagers in one small town keep the memory of Victor L. Phelps alive and well in their minds and on their hearts.

“My grandmother was just so excited when I told her, ‘We’re taking you to Italy.’ She is in great shape for her age, and if there’s anyone willing to make a 16-hour flight, she’s up for it,” Farr said.

He then told his mother, “‘You’re going, too,’ and I would never forgive myself if I don’t go to this,” he said.

“I’m so glad (my mom) is healthy and able to go and really appreciate this,” said daughter Bonnie Farr, who was convinced to make the journey when Stephenson said, "'It’d be more fun if I had another girl along with me.’ It’s just a miracle it’s come together, and it’s really touching this town does this. They really think he’s a hero, and it’s so amazing a town would be so appreciative of one person.”

But for Soglia, Fortilano and others who remember, Victor Phelps represented something bigger than one man.

He represented liberation from tyranny.

He represented freedom.

Related: Beaumont's WWII-era Civil Air Patrol

During the ceremony that will begin in the town hall at Castel Bolognese before moving to the crash site, “We will remember Victor and also our liberation from Nazi-fascism,” Soglia said.

It was a difficult time, when towns along the Gothic Line “were destroyed and there were hundreds of civilian casualties. The liberation of our small towns was a short celebration for all who survived. They had suffered a lot during the German occupation and rebuilding was very difficult,” he recounted.

Multiple posts on Italian Facebook pages have highlighted the impending family visit and coverage in Houston media.

“Local institutions are expected to participate in what will be an exciting and unique event, with a significant resonance that will go far beyond the borders of our small municipalities and reach overseas,” Soglia wrote on one post.

When the family arrives, they will be welcomed by Soglia and fellow members of the Friends of the Senio River Association, then taken to their accommodations at La Compagnia Bed and Breakfast, located 500 meters from the site of Phelps’ crash.

And his family is poised to get the heroic treatment the likes of which villagers in 1944 would have liked to give the man himself beyond immediate shelter on a small farm.

Like Farr and Stephenson, Soglia is amazed that he will be meeting the family within one month’s time.

“It’s almost unbelievable. When I tracked down Joel Farr in 2018, I didn’t believe that an almost novel story would begin. It will be exciting to meet everyone, especially Norma (Sue Stephenson),” Soglia said.

He hopes that witnesses of the crash, including Frontali, will be able to attend the ceremony, bringing with them any remnants of relics collected from the plane. Farr heard one person had recovered his grandfather’s compass from the rubble.

One who witnessed the crash as a child will most certainly be there – Rino Sagrini.

The 88-year-old told Soglia “that he wants to shake Norma's hand and that he absolutely cannot die without doing so.”

What would Victor Phelps think about the attention he’s received abroad?

“He would respect it and be thankful they did it, but he wouldn’t want all the fanfare,” Stephenson said.

Most likely, he’d prefer to sit on the sidelines, with a good glass of wine, raising a toast to liberation and those who, like him, fought the good fight -- many of whom weren’t fortunate enough to make a life back home after their service days were ended, she said.

Farr and his uncle Larry Phelps will honor those men when they rent a car in Berlin after the trip’s end and drive to Stalag 3 in Poland, to see the place where Phelps and others were held captive before their own liberating forces arrived.

Some of those fellow POW's remained part of Phelps' life for years after the war. Bonnie Farr remembers them coming over for Christmas or to gather for a celebration on Liberation Day. "They called them 'uncles,'" Farr remembers his mother telling him.

For those who didn’t survive the camp, whose names aren’t etched into plaques in small villages and celebrated annually with marches and parades, Farr wants to remember their service and sacrifice, as well.

"These men and women were a part of the 'greatest generation.' A lot of them didn't make it back -- my grandfather was one of the lucky ones," Farr said.

Unlike his grandfather, Farr's journey is one of his choosing, done out of respect and with the deep desire to feel closer to the grandfather he knows only through stories told and photographs taken.

"I had no idea a respect post for my grandfathers would turn into all of this, but I am so blessed that it did happen for my grandmother and our family," he said. "To know I will be in the area he was and to travel to the places he stood, it's something I will always remember the rest of my life."

kbrent@beaumontenterprise.com

twitter.com/kimbpix