China Reopening May Not Provide The Boost Expected

Summary

- While economic activity is likely to rebound in China in 2023, economic uncertainty amid a weak housing market could limit growth.

- Chinese households have excess savings, but it is unreasonable to expect the behavior of a nation of savers to mirror the behavior of a nation of consumers.

- Demand for commodities may also be weaker than expected if China's housing market remains soft and demand for Chinese goods from developed countries continues to moderate.

zorazhuang

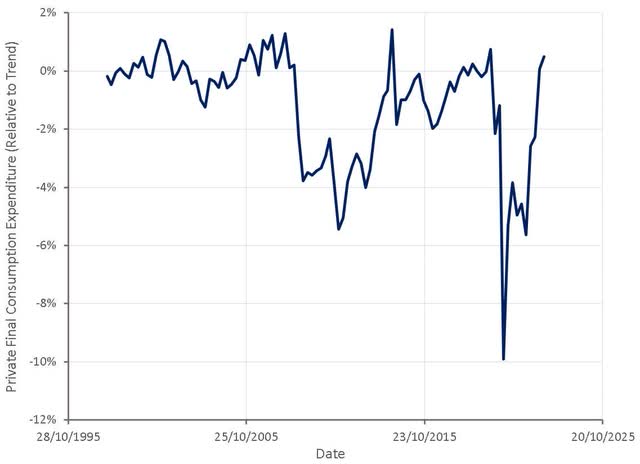

2023 is likely to see a rebound in economic activity in China, but it may not provide the boost that many expect. As a nation of savers, it seems unlikely that excess savings in China will lead to a surge in consumption, particularly with ongoing weakness in property markets.

The Consensus

The consensus seems to be that China's reopening will cause a surge in consumption, directed at sectors like tourism and retail. The savings rate in China was elevated relative to pre-pandemic levels between 2020 and 2022, which has likely increased the spending power of consumers. Travel was also restricted for an extended period of time, which is likely to lead to a surge in travel as restrictions are eased. An end to supply chain disruptions is expected to ease inflationary pressures, but higher manufacturing and construction activity could also lead to higher commodity prices.

These expectations appear to be based largely on an extrapolation of the US experience, without consideration of China specific factors. While all of these things are likely to be true to some extent, factors unique to China could lead to vastly different outcomes than the current consensus.

Excess Savings

Prior to the pandemic, Chinese households saved roughly 17% of their income. In 2022 that figure was around 33%. As a result, it is estimated that the Chinese people have excess savings amounting to approximately 827 billion USD. This increase in savings appears to be more the result of economic uncertainty than pent-up demand though. Consumption in China is likely to bounce back in 2023 and given the excess savings, demand could be relatively strong, but Chinese households may choose to maintain a higher level of precautionary savings over the long-term.

In comparison, it has been estimated that US households accumulated 2.3 trillion USD in excess savings, much of which came from government transfers. While many US citizens likely viewed excess savings as a windfall that could be spent against a strong economic backdrop, Chinese citizens are more likely to view excess savings as hard earned money that should largely be retained given mounting economic uncertainty. Particularly given that Chinese households save mainly in the form of housing and financial investments, which is potentially problematic given the current state of the property market. In 2022, many households favored keeping money in bank deposits rather than purchasing property or investing in the stock market.

Survey data certainly seems to support a cautious outlook by Chinese households. According to a PBOC survey, 22.8% of Chinese households would like to buy more things compared to 58.1% who said they would like to increase their savings and 19.1% who said they would like to invest more. According to another survey, higher income individuals remain relatively confident about their financial situation and employment prospects. 26% of people with an annual household income above 345,000 yuan said they increased spending by greater than 5% from last year. Only 14% of that income group said they significantly cut their spending. For those with an average annual household income below 85,000 yuan, only 12% increased spending, while 27% cut back. The share of urban households wanting to save "for a rainy day" rose to 58%, the highest level since 2014. Part of this caution comes from the fact that China has a relatively weak social safety net.

It is also useful to look outside the experience of the US when considering what could happen with excess savings in China. Japanese households accumulated record financial assets through the pandemic due mainly to lower spending, with cash and deposits accounting for over half of total financial assets. Japanese excess savings were likely in the vicinity of 400-500 billion USD. While consumption in Japan post-COVID has been fairly robust, it is weak relative to the US, and this could be indicative as Japan is also a nation of savers.

Figure 1: Private Final Consumption Expenditures in Japan - Relative to pre-COVID Trend (source: Created by author using data from The Federal Reserve)

Consumption

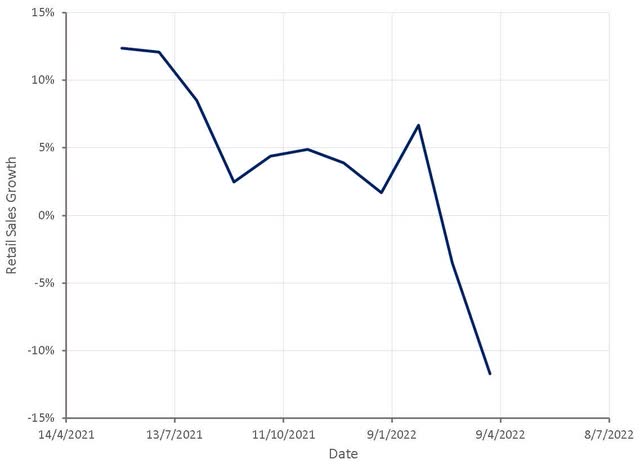

Consumption in China took a significant hit in 2022 and this is largely where excess savings have come from. As a result, it would be reasonable to expect consumption to bounce back somewhat in 2023.

Figure 2: Total Retail Sales of Social Consumer Goods (source: Created by author using data from www.china-briefing.com)

As China's mobility index improves, local governments in some major cities are rolling out consumption vouchers to cash in on consumers' pent-up desire to spend. Beijing is planning on giving low income residents (approximately 300,000 people) a cash subsidy to offset the impact of rising food prices. There have also been protests in Wuhan and Dalian in relation to cuts to medical care benefits. This goes against what would be expected if excess savings and pent up demand are driving strong consumption growth. This appears to support survey data suggesting that consumers remain cautious and are reluctant to spend savings due to economic uncertainty.

Household borrowing demand is also weak, which could be explained by excess savings reducing borrowing needs or economic uncertainty impacting borrowing demand. The net increase in the balance of medium- and long-term bank loans to households in 2022 was 2.75 trillion yuan, growing 55% less than last year. New loans reached their lowest level in eight years, and the decline was the steepest since 2010, before which data is unavailable. Condo transactions and new mortgages both suffered slowdowns. Money in China is stuck in banks, with the gap between deposits and loans hitting the highest on record at the end of last year amid an uncertain economic outlook.

Exports and Imports

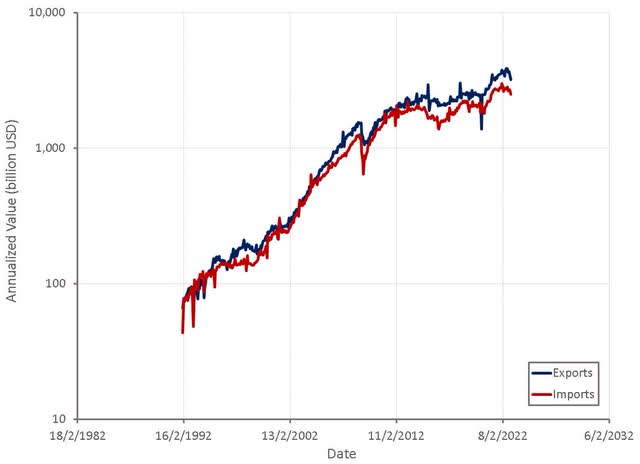

China's exports and imports are also indicative of the state of China's economy through the pandemic. Import and export levels were actually quite strong throughout most of the pandemic, falling somewhat towards the end of 2022, but still quite high relative to pre-COVID levels. This suggests that trade wasn't that impacted by the pandemic and hence exports and imports should not be expected to change significantly as the economy reopens.

Figure 3: China's Exports and Imports (source: Created by author using data from The Federal Reserve)

Monetary and Fiscal Policy

When evaluating the impact of China's reopening, it is important to consider China's monetary and fiscal policy through the pandemic. China took a far more prudent approach to supporting their economy through COVID lockdowns than the US. Despite pandemic headwinds, China still reported GDP growth of 2.3% in 2020 and 8.1% in 2021.

China did not engage in universal cash-in-hand support for the economy like the US. Rather, the financial system was used to support the private sector, preferential tax policies and fee cuts were implemented and government spending was increased. Preferential tax policies and fee cuts have included refunds, waivers, and reductions to corporate income tax, value-added tax, and individual income tax. These were often targeted at industries that were particularly hard-hit by the pandemic and individuals working in essential roles. The government pledged a total of 374 billion USD in tax refunds and reductions in 2022.

China is trying to transition to a consumption led economy in order to avoid a growth trap, but this process is being complicated by the pandemic. Infrastructure investments have been one of the government's main strategies for boosting economic growth. This is somewhat problematic though as the return on these investments has been declining. Local governments have been supporting infrastructure spending and public projects using special-purpose bonds. The 2021 SPB quota was 547 billion USD, around 50% of which was used to invest in transportation and infrastructure projects, and around 30% went to affordable housing projects and social undertakings.

The central bank's reserve requirement ratio has also been used to support lending, along with the loan prime rate. The loan prime rate is the benchmark corporate loan and mortgage rate for commercial banks set by the PBOC.

COVID

Any rebound in economic activity in China will also be dependent on the spread of COVID. Regardless of government restrictions, consumption is likely to be weak during periods with large COVID waves. Due to the limited efficacy of vaccines at limiting the spread of COVID, it would be reasonable to expect multiple waves over a 6+ month period based on the global experience in 2021 and 2022.

According to the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) deaths and severe cases are down almost 90% since the infection peak. There has also been a sharp decline in COVID-19 patients at hospitals and fever clinics. According to the CDC, the number of patients at fever clinics peaked on December 23 with 2.87 million. At the peak there were reportedly 4,273 deaths per day.

Manufacturing

China's factory activity shrank more slowly in January after Beijing lifted tough COVID-19 curbs late last year, a private sector survey showed. China's Caixin/S&P Global manufacturing purchasing managers' index was 49.2 in January, up from 49.0 in December, indicating an ongoing contraction in activity. This stands in contrast to a better-than-expected official PMI survey. This may be due to the fact that the official PMI largely focuses on big and state-owned Chinese businesses, whereas the Caixin survey centers on small firms and coastal regions. China's official manufacturing purchasing managers' index rose to 50.1 in January. Non-manufacturing PMI rose to 54.4, the highest level since June 2022, due in part to services and construction activities. These figures suggest an improvement in economic activity but this rebound has not been particularly strong so far. This data is complicated by the fact that COVID was still spreading in January and the Lunar Year also occurred in late January.

Travel

Domestic travel in China is beginning to normalize, with flight activity sitting at 65% of pre-pandemic levels in early December. According to Ctrip, the Chinese travel agency, air travel searches increased 900% when the Chinese government announced the end of restrictions. Domestic tourism generated an estimated 55 billion USD revenue during the Lunar New Year period, approximately 73% of that in 2019. A total of 308 million tourism trips within China have been made during the current holiday period, up 23.1% from 2022's Lunar New Year break and marking a recovery to 88.6% of the number in 2019.

In 2019, more than 150 million Chinese travelled abroad and spent an aggregate amount of 255 billion USD (17% of global outbound travel market). Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore are likely to be significant beneficiaries of this as their economies are reasonably dependent on Chinese tourists.

International travel is rebounding far more slowly though. Global airlines are currently only offering 11% of 2019 capacity levels, but this figure is expected to hit 25% by April. Airfares from China are now 160% higher than prior to the pandemic, due to limited supply, which may restrict demand.

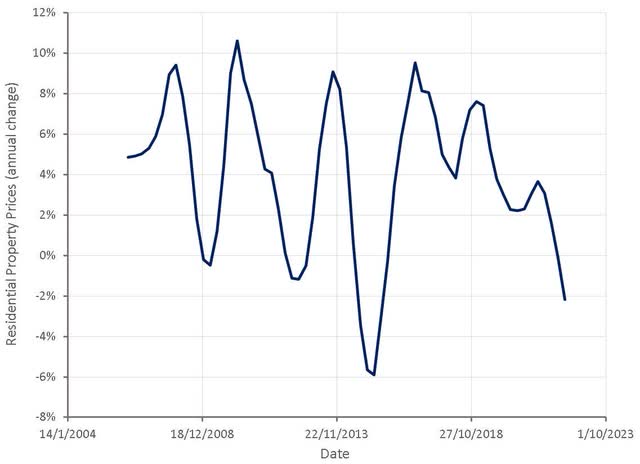

Housing

The China reopening story could be undermined by the property market, as falling home prices, sales and investments have been pressuring China's economy. The property market is likely to remain weak, amid sluggish income expectations coupled with ongoing concerns about home delivery. This is important, not just because construction is an important driver of economic activity, but because housing is one of the primary investment vehicles for Chinese citizens and hence house prices are likely to have a large impact on consumer sentiment.

Tier-1 Chinese cities, like Beijing and Shanghai, have become some of the most expensive in the world, making it difficult for new buyers to enter the market. Due to housing affordability issues, the government recently began introducing measures that discourage housing speculation. Their ability to effectively do this has been hampered by the fact that real estate is critical to China's economy.

The government clearly does not want a real estate crash and as a result has been trying to support the industry in an attempt to counter an ongoing liquidity squeeze that has affected developers and caused project delays. These measures have included lifting a ban on fundraising via equity offerings for listed property firms.

Prior to the introduction of the "three red lines" two years ago, Chinese developers were able to utilize a higher degree of leverage than occurred during Japan's and the US's property bubbles. Home buyers were also offered intergenerational and zero-deposit mortgages in much larger volumes than official statistics suggest.

China's home prices fell at an accelerating rate in December, despite a range of support measures. Home prices in 100 cities fell for the sixth month in a row in December, declining 0.08% from a month earlier after falling 0.06% in November. The decline in prices has also become broader based, with prices falling in 68 cities in December, compared to 57 in November.

Figure 4: Residential Property Prices in China (source: Created by author using data from The Federal Reserve)

Oil

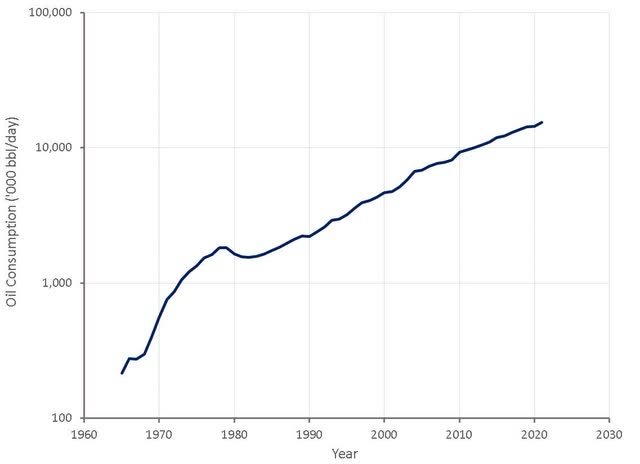

Oil demand in China was quite weak in 2022, which helped to ease pressure on tight oil markets caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Between 2021 to 2022, China's import of crude oil declined by 4%, compared to a 12% increase in 2019. A return to a more healthy level of demand could cause oil prices to rise significantly and contribute to inflationary pressures. S&P believes that China's oil demand could exceed 15.7 million bbl/day in 2023, a 700,000 bbl/day increase over 2022. The increase in air travel caused by China's reopening is also likely to be an important contributor to oil demand growth in 2023.

Figure 6: Chinese Oil Consumption (source: Created by author using data from BP)

This situation is complicated by the fact that China is a large refiner of oil and also has enormous oil storage capacity. These both could potentially cause significant short-term fluctuations in demand.

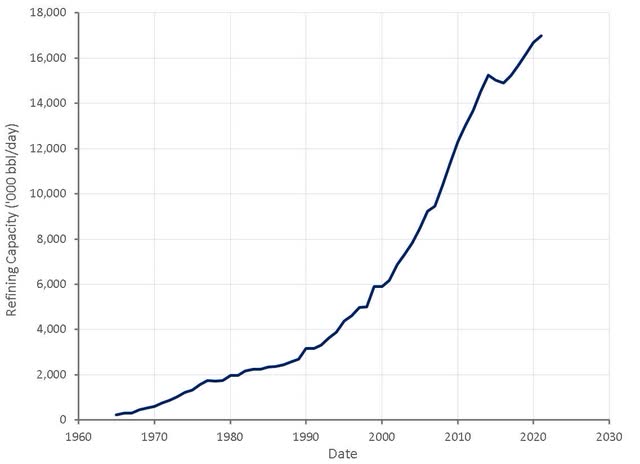

China is likely now the largest oil refining country in the world, although it has been struggling with overcapacity. The Chinese government is attempting to grow its high value-add chemical industry while capping total crude refining capacity. Privately owned, "teapot" refineries, have been the target of government attempts to reduce surplus capacity and emissions. China's "teapot" refineries account for a fifth of Chinese crude imports. In an attempt to remain profitable, these refiners have turned to discounted oil from Iran and more recently, likely Russia.

Saudi Aramco has been attempting to lock-in Chinese demand and are pursuing investment opportunities in integrated downstream projects. In 2021, the combined share of crude shipments from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Kuwait to China's independent refiners accounted for 32.5%.

Figure 5: Refining Capacity in China (source: Created by author using data from BP)

China has their own Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which is estimated to have a total capacity of around 500 million barrels. These reserves were built out in three phases over recent years. China is more likely to keep these reserves for a genuine emergency than use them to offset high prices like the US did in 2022. The build up of these reserves would have been a reasonably significant contributor to demand in the 2010s though.

This compares to the US' SPR capacity of 714 million barrels. It is estimated that the storage volume was approximately 370 million barrels in January 2023, down by around 270 million barrels in 2022. It is believed that below roughly the 120 million barrel inventory level, drawdown capacity becomes significantly reduced.

It would be reasonable to expect demand for other commodities to rebound in 2023, driven by China's reopening. Iron ore demand in China was reasonably robust in 2022 due to government infrastructure investments. Absent a rebound in China's property market, iron ore prices could soften in 2023. Cement prices will also depend on China's property market.

Outside of price speculation in anticipation of China's reopening, there appears to be little increase in commodity prices that would be suggestive of a surge in demand.

Conclusion

Many US households likely viewed excess savings built up during the pandemic as a windfall, and hence have chosen to spend these savings. This spending also occurred with an extremely strong economy and tight jobs market as a backdrop, providing consumers with significant reassurance.

Chinese households are more likely to view their savings as hard earned, and a necessary buffer given an uncertain economic outlook. It is therefore unreasonable to expect a surge in spending, similar to the US.

The entire world ex-China largely emerged from COVID at around the same time in 2021 with excess savings and pent-up demand. Supply chains at the time were still vulnerable and large backlogs existed in many areas. China is now emerging from COVID against a backdrop of normalizing supply chains, declining backlogs and softening global demand. It is unreasonable to think that this will result in a growth or inflation surge that parallels the 2021/2022 experience.

This article was written by

Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.