Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy. (Source: AP/File)

As he looks back on the year since the Russian invasion, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy can draw satisfaction from his country’s performance on two fronts. In the battlefields of the east, his soldiers and generals have held out against a larger, better-armed enemy; in the west, he has routed his opposite number, Vladimir Putin, in the war of narratives.

Zelenskiy has kept the US and Europe behind Ukraine, which has in turn given his military the morale and munitions it needs to keep Russia at bay. His personal charisma and adroit diplomacy helped to overcome early American and European reluctance to antagonize Putin, and to extract ever more potent weapons from NATO nations. Western commitment to the Ukrainian cause was underlined this week by US President Joe Biden’s visit to Kyiv.

But as he looks ahead to the second year of the conflict, the Ukrainian leader should direct more of his energies to a conspicuous gap in his communications campaign: the Global South. In most of the developing world, Ukraine has been unable to challenge Russia’s superiority in the war of narratives. Here, too, Kyiv will need some Western assistance — but it also has some powerful weapons of its own.

In the first phase of the war, the Global South didn’t feature prominently in Ukrainian priorities. Zelenskiy recognized that ensuring a steady flow of Western arms and assistance was absolutely crucial to preventing all of his country going the way of the Crimean peninsula in 2014, when Putin took advantage of an absence of support from the US and Europe. In the spring of 2022, the West’s attention and engagement were existentially important to Ukraine.

But having secured his country from annihilation and annexation, Zelenskiy will need the support of the Global South to pressure Putin to end the war. When the time comes, Ukraine will also require an international consensus to force Russia to pay reparations — and be held accountable for war crimes.

This is dawning on the president and his cabinet. “There is a strong awareness in the Ukrainian leadership that the Global South is a blind spot,” says Fabrice Pothier, CEO of the political consultancy Rasmussen Global, who has advised the Ukrainian government. Addressing a joint session of the US Congress late last year, Zelenskiy characterized the conflict as a “battle for the minds of the world,” and talked of the need to ensure victory for “countries of the Global South” as much as for Ukraine.

Bringing the developing world onside will take more than soaring rhetoric. As in the early days of the invasion, the Ukrainians find themselves severely lacking in the resources required for a war of narratives. For a start, Kyiv has only a fraction of Moscow’s diplomatic wherewithal. “They are struggling to find the right channels,” says Pothier. “They only have five ambassadors in the whole of the African continent, for instance. They can’t compete with Russia in that respect.”

Ukraine’s foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba, has neither the rolodex nor international name-recognition of his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov. Since the start of the war, Lavrov has flown around the developing world to sell the Russian narrative — when he’s not been receiving foreign ministers from the Global South in Moscow. Kuleba has not been ratcheting up the frequent flyer miles at anywhere near the same pace, nor has his red carpet seen much wear.

In the West, Zelenskiy has made up for his travel limitations by delivering video addresses, whether to the European Parliament, to French lawmakers or to the World Economic Forum. But this approach doesn’t work with skeptical audiences. When he addressed the African Union last summer, only four of 55 heads of state attended the virtual session. Many more African leaders have been happy to host Lavrov, lending a patient ear to his propaganda about Ukrainian (and Western) perfidy.

The developing world has, for the most part, voted against Russia in United Nations motions pertaining to the war. But there have been significant fence-sitters. Just days after hostilities began, 35 nations — all from the Global South and collectively accounting for nearly half the world’s population — abstained from a vote condemning Russia’s invasion. In October, the same number abstained from a vote to condemn Moscow’s annexation of parts of eastern Ukraine. (In both instances, only five countries voted against the motion.)

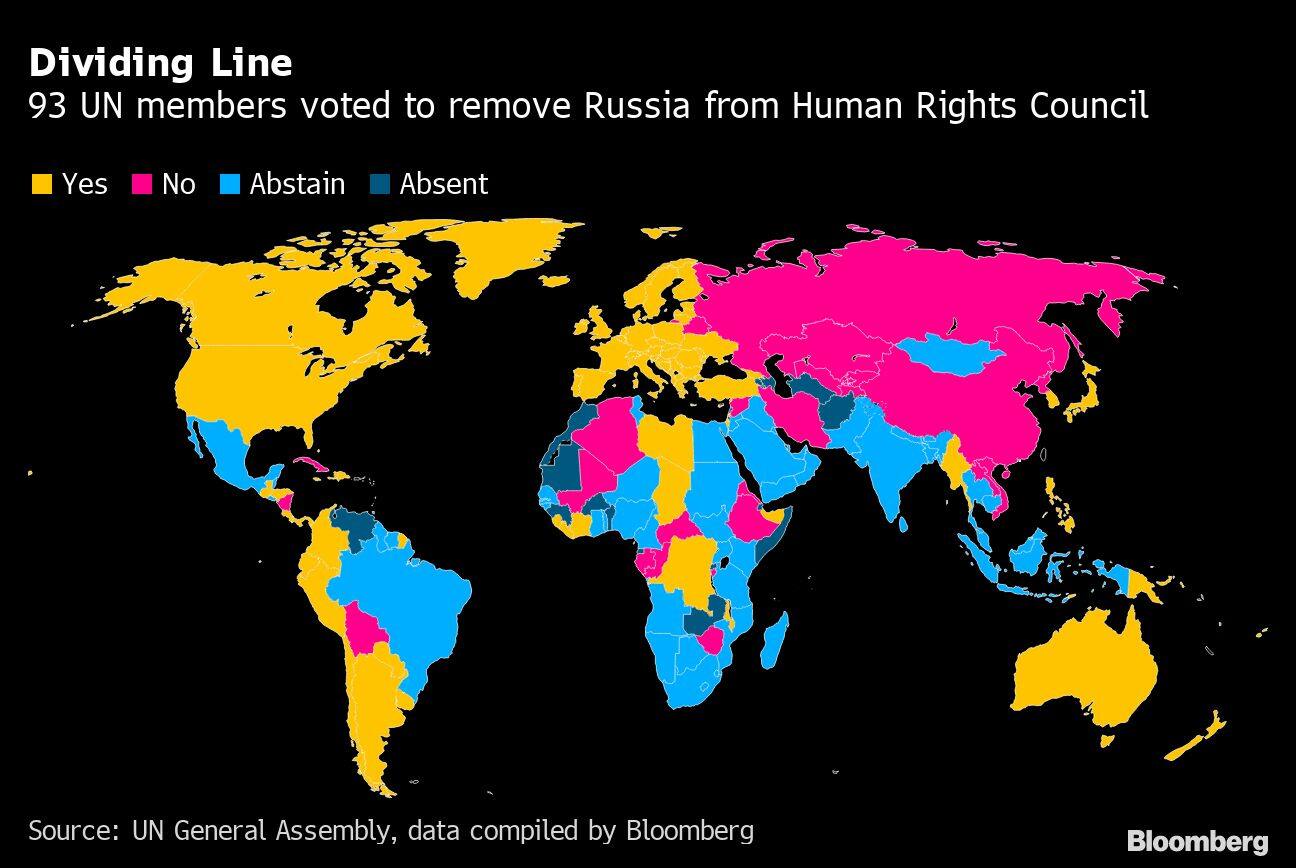

And keep in mind that those were symbolic, non-binding votes — like the one scheduled for later today, on a motion stressing the urgency of finding “a comprehensive, just and lasting peace” and calling for the support of UN members and international organisations. When it comes to actionable motions, sympathy for Russia has been stronger. In April, 58 countries abstained and 24 voted against a motion to suspend Russia from the UN Human Rights Council over its conduct in Ukraine. This was just days after the world first glimpsed the gruesome images of murder and torture of civilians by Russian soldiers in Bucha, near Kyiv.

The vote wasn’t enough to keep Moscow on the council, but it put paid to any notions that Putin was isolated and friendless. The naysayers and fence-sitters included the Global South’s most prominent nations: China, Ethiopia, Iran and Algeria were among those that voted against, while India, Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria and South Africa abstained.

Several factors explain this willful disregard of the facts of the war. The leaders of many developing nations, especially in Africa, retain fond memories of Moscow’s support during their freedom struggle against Western colonial powers. Some are more recent beneficiaries of Russian largesse. Still others are leery of losing long-term military ties. A few are opportunistically using the war to extract cut-price oil and gas from Russia. And some are taking their cues from China, Russia’s principal ally.

Overcoming this combination of reasons will require different narratives than those that have given Zelenskiy so much traction in the West. True, as Richard Gowan of the International Crisis Group recently noted, violations of sovereignty are something that even autocracies don’t like: 21 of the 55 states that Freedom House classifies as “not free” supported Ukraine. Still, many countries in the Global South may not buy — or care — that allowing Putin to annex Ukraine would merely encourage him to demand other territories in Europe. Persuading developing countries that paying more for gas today will secure their future freedoms is a hard sell.

But Zelenskiy can tell other stories that will resonate in the Global South. Nations that have suffered colonial and imperial oppression can be persuaded Ukraine now faces both those things.

“A Ukraine narrative of a shared experience of colonialism and imperialism would be very powerful in the Global South,” says Gaspard Estrada, a political scientist at Sciences Po who specializes in Latin America. “Zelenskiy should also say, ‘Like you, we reject the notion of areas of influence.’ This would be an especially strong argument with the new leftist leaders in Latin America, because it is their argument.”

Zelenskiy can invoke Cold War-era ties, too. Rashid Abdi, a geopolitics analyst and fellow at the Rift Valley Institute, points out that many African leaders who retain a sense of loyalty to the old USSR were trained and educated in Ukraine, not Russia. “Ukraine has a longer relationship with Africa, more beneficial to Africans,” he says. “It’s also a more diversified relationship, not only about wheat and fertilizer supplies. The Ukrainians have been very generous with scholarships, and before the war there were tens of thousands of African students there.”

Zelenskiy can also also reach out over the heads of political leaders to tap into the pro-Ukrainian sentiment of ordinary people. “Among the public, it is the Western perspective — that Russia is the invader — that prevails,” says Monica de Bolle, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “This is manifested in op-ed pieces, academic events and on how the war is portrayed on TV. There is admiration for Zelenskiy, even if it’s not as pronounced as in the West.”

Since he must still spend time and energy to keep his Western benefactors onside, the Ukrainian leader will need surrogates to help carry the word to the developing world. Western leaders, given the complicated history of their countries in the Global South, may lack the credibility to pull that off. But Zelenskiy should be able to recruit proxies from leaders of countries in Russia’s periphery, who know all too well the implications of Moscow’s imperial ambitions.

The West has a role, too: To provide economic and diplomatic cover for any losses that developing countries may incur if they get off the fence on Ukraine’s side. Favourable terms of trade, debt forgiveness and fresh aid: The US and European nations know how to reward those who choose to be on the right side of history.

Bobby Ghosh is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering foreign affairs. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Credit: Bloomberg