Starbucks: Taking A Deep Dive Into Its China Exposure

Summary

- Starbucks has made an aggressive push into China over the last five years.

- As more Western companies seek to reduce exposure to China, Starbucks has sought to increase it.

- It's not clear that the unit economics on Chinese stores make good financial sense.

Nadya So

Go East, Young Man

Howard Schultz, current outgoing and three-time CEO of Starbucks (NASDAQ:SBUX), has made no secret of the fact that the coffee company's future lies in China. The company operates almost 9,000 stores across the United States, and while incremental growth opportunities still exist, the company is particularly excited about the opportunity to continue its plan to make coffee part of the culture in China.

But is that growth secure? And how should investors value it? Starbucks has been quite upbeat about its prospects in China, but, as many businesses are well aware, operating in the country as a Western guest can be fraught. Read our previous coverage on Starbucks here.

Up to this point, Starbucks' excursion in the country has gone off relatively well, though it faces stiff competition from Chinese upstart coffee chain Luckin Coffee (LNKCY). We think that investors looking at Starbucks's China expansion without properly assessing the risks the company faces there. At a bare minimum, we hope in this article to inform investors about the extent to which the global coffee chain has invested within the country.

What's the Risk?

First, some table-setting. The opening of China in the 2000s was, if not the opening salvo of globalization, the rocket fuel that made it a reality. Western firms across the world pulled operations and labor from high-cost countries to China where goods could be produced more cheaply than ever before.

In our current age of apparent de-globalization, Western companies are re-assessing their level of dependance on China's labor and, by extension, government. In July 2022, Jeep (STLA) ceased operations in China with the CEO stating "[w]e have been seeing over the last few years more and more political interference in the world of business in China."

Jeep is not alone. In recent years, Apple (AAPL) has worked to reduce its footprint in the country. Hasbro (HAS), Volvo (OTCPK:VLVLY), and adidas (OTCQX:ADDYY) have also followed suit.

In addition to simple government interference, China has a history of implementing stringent capital controls designed to keep money in the country. These measures are meant to ensure that as few Renminbi [RMB] as possible flow out of the country and into the hands of foreign bank accounts.

Uber (UBER) learned this lesson the hard way in 2016 when it was forced to sell its Chinese operation to rival Didi Chuxing (DDIY). It did so ostensibly because Chinese regulations were coming into effect that stipulated a long list of requirements which needed to be met by ride-sharing companies, but the reality is that Chinese companies were likely going to receive preferential government treatment, leaving Uber to bleed out through through bureaucratic overload.

The Chinese government has not historically had a problem with, say, Apple or Jeep setting up manufacturing operations. These factories bring cash inflows to the country. Operations like Uber (and Starbucks), however, take money from Chinese consumers and make their way onto western company balance sheets. The question, then, are the outflows.

The timing of the new laws seemed... curious. They were set to take effect just as Uber found its footing on the path to profitability. To this point, when asked about Uber's foray into China, Didi CEO Jean Liu said it was "cute."

Further, the war in Ukraine has raised awareness around that globe that China could make a move on Taiwan at any time. A war in Taiwan would almost certainly be catastrophic for Starbucks, as access to its capital investments in the country would rapidly be cut off.

So with all that said, why hasn't Starbucks suffered the same fate as other Western firms? And just how exposed is it to potential risks?

Starbucks In China

Starbucks has showcased its growth in China over the years and has also broadcast more subtle signals to investors that it is taking the expansion incredibly seriously. Belinda Wong, the Chairwoman and CEO of Starbucks China, made her first appearance on Starbucks's quarterly earnings calls in May 2022--she has been on every subsequent call and fielded questions at Starbucks's September 2022 investor day. The earliest appearance we could find from her was a Starbucks investor day presentation held in China in 2018 where she opened her remarks by stating that she was there "to talk about the company's fastest growing and most strategic market in the world: China."

The appointment of Laxman Narasimhan as the incoming CEO to replace Howard Schultz is also indicative of the company's expansion aims in China. Narasimhan does not come from the coffee industry, but from Reckitt Benckiser (OTCPK:RBGLY), the maker of Lysol, where he served as CEO. His selection to head up the world's largest coffee retailer may be a head scratcher until you consider that Reckitt's second largest market is China, and Narasimhan has spent considerable time there (he spent his inaugural week as CEO of Reckitt in China) and, presumably, has a deep working understanding of how to get things done in the country.

Starbucks has also made significant capital investments within China over the years to enclose the bean-to-cup loop completely within the country. In 2013 the company announced its first Asian-based Farmer Support Center in the Yunnan Province. Farmer Support Centers are capital investments made by Starbucks to train local farmers on sustainable practices and provide access to agronomists and other resources. After this significant investment, Starbucks ramped up its purchases of coffee from the province at a rapid clip, importing to United States from Yunnan more than five times the amount of coffee in 2014 than it did in 2013--a gesture sure to not have gone unnoticed by the PRC.

In 2017, the company launched its first single-origin Yunnan coffee. In the press release, Starbucks declared that "With firm support from the local and provincial governments, the Starbucks South of the Clouds Blend is now available in Starbucks stores in numerous locations across Asia and the United States."

The company has also invested significantly in the well-being of its Chinese staff, offering benefits that aren't available even to American employees. Howard Schultz announced in 2016, alongside Jack Ma, at the Starbucks China Partner-Family Program in Chengdu that full-time baristas and supervisors would receive a monthly housing allowance.

For a company that has spent much of its time in the United States over the last few years fending off unionization attempts, employee housing allowances may strike readers as a bit out of character. These actions, however, are likely not lost on the Chinese government.

In perhaps the largest-scale instance of the nature of the relationship between Starbucks and the Chinese government, Xi Jinping publicly appealed, and wrote a letter, to Howard Schultz in 2021 to assist with easing tension between the U.S. and China.

(Note: For a deeper dive on Starbucks's positioning within China and its cozying up to Chinese Communist Party leadership, please refer to Clint Rainey's fascinating article on Starbucks from Fast Company.)

The Economics

Starbucks has invested a lot of time, energy, and money in China. Will it pay off? The company talks quite a bit about store count, but we want to dive into the underlying economics for a moment.

China's average income per capita is still less than RMB 12,000 (roughly $1,700) annually, which reflects the degree to which its massive population remains rural. Of course, the countryside differs from the big city, and China's so-called tier system gives us a glimpse into Starbucks's potential opportunity. Occupants of Tier-1 cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen) possess the greatest purchasing power, and Tier-2 cities (Chengdu, Chongqing, Wuhan, Nanjing) are next in line. Just for reference, the rankings--at least from the South China Post--go down to the fourth tier.

Starbucks currently has the majority of its locations in Tier 1 and some Tier 2 cities. Figures for average income in these cities is relatively difficult to come by, but estimates from 2020 show Tier 1 city average annual disposable incomes to RMB 69,000 ($10,125), while Tier 2 cities range from RMB 35,000 ($5,135) to RMB 61,000 ($8,951). Tier 3 cities range from RMB 39,000 on the high end to as low as RMB 27,000 ($3,961). We'll return to these figures in a moment.

The Chinese are historically tea drinkers, with coffee playing a minimal role in day-to-day life for most. The country produced 3.1 billion metric tons of tea in 2021, and estimates show that China consumes most of that amount itself, exporting only 15% of what it produces.

On the coffee side of things, it's reported that Chinese citizens currently drink only 6.2 cups per year of coffee (Starbucks estimates, somewhat generously, that consumption per capita is in the double digits). Compare this to the fact that 62% of Americans drink coffee daily, and the average drinker consumes 3 cups per day. Based on this disparity alone, the market and runway to introduce China to coffee as a daily drink seems almost unfathomably large. As alluded to a moment ago, however, the true consumption per capita of coffee among Chinese is the subject of much debate.

Disposable income, however, is not. Not only are disposable incomes in China significantly smaller (the U.S. recently posted average disposable income per capita of $56,761 annually, more than 5x the total average annual disposable income in a Tier 1 Chinese city), but coffee is significantly more expensive there compared to the United States.

At the time of this writing, a plain, black grande (medium, for those not in the know) drip coffee cost $2.95 at a local Starbucks, with a venti (large) costing $3.25. A blogger on a recent trip to China posted that a cup of coffee (she didn't specify cup size, sadly) at Starbucks in Beijing cost her $4.50.

Now, just a quick mental exercise shows us the challenge here--we have a country where: A) coffee is not a culturally important drink, B) prices are higher than in the U.S., and C) disposable income levels are considerably lower.

Let's say that a citizen of a Tier 1 city--say, Shanghai--takes up drinking coffee. Their habit has them drinking six cups of coffee per week from Starbucks. Let's also say that they aren't drinkers of plain black coffee, and his drink costs the equivalent of $5.00. That works out to $120 per month, and $1,440 per year--or 14% of his disposable annual income, a not insignificant amount.

Due to the nature of the product, this presents a real problem. (And yes, we are aware that average income can be massively skewed within Tier 1 cities since these cities are home to significant ultra-wealthy populations). However, these wealthy individuals can't be consumers of coffee in the same way they can be consumers of Hermes handbags or Lamborghini sports cars. A rich and a poor person, after all, can theoretically handle roughly the same amount of caffeine per day. Profit in coffee depends on one thing--volume.

Starbucks is also hounded by low-cost competitors. Luckin operates a lower-cost model than Starbucks and 7-11 has a significant, and growing, presence in China as well. It is entirely possible that China may adopt coffee culture. After all, Starbucks changed the game for coffee in the United States, it's not impossible for the company to pull off a repeat performance. The major question, however, is whether or not Starbucks will have a profitable slice of the cultural aura it will help create.

Location, Location, Location

Starbucks recently opened its 6,000th location in China, and has ambitions to open 9,000 stores by 2025.

Unfortunately, the company's locations are heavily skewed to--you guessed it--Tier 1 cities. Of the just over 6,000 locations in China, a staggering 1,000 are located in Shanghai alone. (For reference, New York City has a little under 300 Starbucks locations and has a population of about 9 million, while Shanghai has an estimated 29 million.)

Chinese stores thus account for about 30% overall of Starbucks's 18,000 locations. This figure alone is somewhat misleading, however. In its recent earnings announcement, the company pointed out that its two largest markets--the United States and China--account for 61% of its sales, with China's store count clocking in at just under 40% of overall U.S. store count. Thus, it is vital for the company (and the stock) that the locations in China succeed and, more importantly, that they continue to multiply.

However, as alluded to above, store economics seem to be working against Starbucks in China. Tier 1 cities alone will, unfortunately, not fully support the growth that Starbucks desires in the country (the company's expansion plans from its recent investor day seem to confirm this). While we believe that the recent 28% decline in sales is largely due to the latest COVID lockdown wave within the country and is probably transitory overall, it still seems clear that the growth target for Starbucks in China is probably unfeasible without breaking into Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities.

At the company's recent investor day, executives claimed that to reach its goal of 9,000 stores, the company will expand locations into 70 new cities. For reference, there are roughly 19 Tier 1 and 'New Tier 1' cities in China, 30 Tier 2 and 71 Tier 3 cities.

Our ambition is to enter 70 more new cities as well as to expand our store count by 50% more to operate 9,000 stores in China by 2025. 9,000 stores, this is close to the number of company-operated stores in the U.S. today. It means we will open one new store nearly every 9 hours for the next 3 years. We expect our new stores to continue to deliver 2:1 sales investment ratio with a payback period of less than 2 years.

This quote is from the remarks of Sara Kelly, Chief Partner Officer, at the investor day. Her number of expansion cities implies a significant amount of penetration into Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities. The question of whether or not Starbucks can be competitive in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities, however, is... debatable at best. The same Starbucks habit that comprises 14% of a Tier 1 resident's disposable income represents 26% of the high end of a Tier 2 resident, and as much as 36% for a Tier 3 city dweller. These figures aren't exactly inspiring, especially since the majority of China already turns to tea--a cheaper alternative--for their daily caffeine fix.

Kelly's comments on how to successfully implement this strategy were as follows:

Despite our growth, China's coffee market is still in its early stages with huge potential to expand the addressable market. Per capita demand for coffee in China will grow further from 12 cups per year to 14 cups by 2025. By comparison in Japan, per capita consumption of coffee approaches 200 cups per year and in the U.S. here, close to 380 cups. China's urbanization rate is expected to increase to 75% and the number of middle-class households in China is expected to grow another 70% to $395 million within this decade.

Whether or not Starbucks can succeed by focusing exclusively on Tier 1 cities also poses a major question mark. Given the problem of volume that we raised earlier, it is unclear whether or not these large cities will have enough habitual Starbucks consumers to support these locations, or--maybe more importantly--whether the government will allow such a high concentration of a Western corporation in its largest cities.

The Investment Already Made

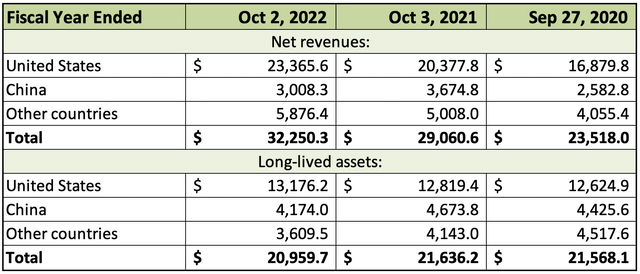

To this point Starbucks's investment--and therefore risk--is quite significant. Of the company's 86 registered subsidiaries, 19 are in China. The company has expanded its corporate office footprint in Shanghai from 175,000 square feet of space in 2021 to 225,000 square feet in 2022 (p. 22).

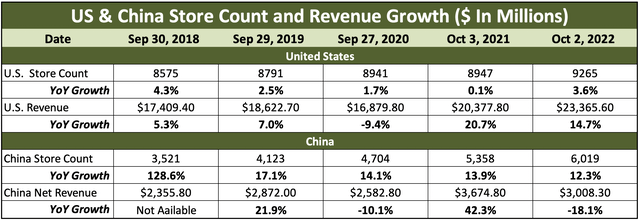

Company Reports, Author Formatting, numbers in millions

Further, while China accounts for roughly 10% of overall revenues, it holds roughly 20% of the company's long-lived assets.

For this, the numbers from the Chinese stores haven't converted well to dollars. China's 6,000 stores, by our math, have an average unit volume [AUV] of $500,000 per year, while locations in the United States have an AUV of $2,609,000 per location annually. Importantly, we are excluding the figures from Q4 2022, which showcased the 28% drop in Chinese store sales largely due to a fresh wave of lockdowns.

This poses a major problem to the narrative, and, we suspect, is a reason why the metric Starbucks pushes the most is store count and not AUV. Due to the fact that the coming 3,000 store expansion over the next two years will push Starbucks into lower-revenue cities, one can imagine a scenario where Chinese AUV of Starbucks stores declines overall, or remains flat at best.

Assuming that the AUV can be grown to $600,000 as the store count grows (aggressive, we think), we can expect an additional $1.8 billion in revenue from the added Chinese stores.

We can't help but wonder if this reflects a corporate attitude that prioritizes total addressable market over pretty much everything else--that the fact that China simply has more people is driving a big portion of strategy. This is evidenced by the fact that Chinese Starbucks locations pull an even lower AUV than other international stores (principally Japan with 1,630 locations, and the U.K. with 318). The total number of international stores ex-China is 2,018.

Using the net revenues provided above of $5.8 billion, we see that the AUV of the other international stores is even higher than the U.S. AUV at $2.9 million per store.

The Current Valuation

Starbucks first broke out revenue from its Chinese stores as its own reportable revenue segment in its FY 2020 10K. Prior to that, Chinese revenue was rolled up in the international segment. The company has broken out store count, however, going back as far as 2012 when it reported 278 open stores in China. We believe that much of the current growth in the stock is based upon growth prospects in China, and we believe a re-rate is on the horizon given the large amount of geopolitical and overall country risk.

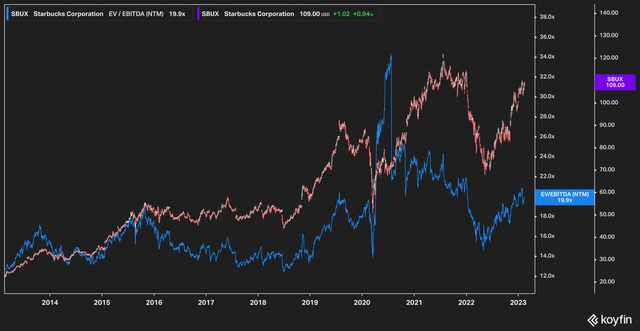

SBUX Price vs EV/EBITDA (Koyfin)

In the above chart we see an overlay of stock price and NTM EV/EBITDA going back ten years. Towards the end of 2015, Starbucks found itself in a bit of a rut. The stock price traded in a sideways range from close to the end of 2015 until right around the start of 2019 when the things began to brighten up.

The reason for this, we believe, is that at the end of 2018 a strategic shift took place at Starbucks. The company had been kicking around the idea of Chinese expansion in earlier years--it even hosted a China Modeling Conference Call with analysts in late January 2018--but management began to discuss business development in China and the U.S. as the top strategic priority in conference calls throughout 2018, culminating in an December 2018 investor day where then-CEO Kevin Johnson said that the company wanted to "drive progress against our 3 strategic priorities: number one, accelerate growth in our targeted long-term growth markets, the U.S. and China; number two, expand the global reach of the Starbucks brand through the Global Coffee Alliance; and number three, increase returns to shareholders."

When you look at the numbers from that time forward, however, it seems clear that the lion's share of the investment was destined for China.

In 2019, Starbucks began providing year-over-year comps for Chinese stores, and the numbers were music to Wall Street's ears--growth (in terms of store count, at least) was back at Starbucks, and the stock price was off to the races.

We hope that we have shown, however, that simply adding stores isn't enough, and not all stores are created equal.

Given the relatively low-grade revenue quality and, we think, potential of these stores, combined with the capital outlay that Starbucks has already made throughout the country, we think the shares are at a significant risk to re-rate based on country and geopolitical risk.

Prior to the Chinese 'boom,' so to speak, in the stock, the company traded for several years in the 15x NTM EV/EBITDA range. With current 2024 EBITDA estimates at $8 billion, this gives us a target price of $86 per share.

The Bottom Line

We believe there are a number of issues with Starbucks' rapid expansion into China.

- Coffee is not an integral part of Chinese culture. Even as it grows, we are concerned that potential customers may choose to buy cheaper coffee elsewhere with their disposable income. The risk that coffee culture may not take root the way the company projects is quite large.

- China's government has a history of interfering with business--particularly Western business. While Starbucks currently has a good relationship with the PRC, we believe this could turn on a dime.

- As of now, the investments made in China by Starbucks do not appear to be paying off economically, as AUVs are down compared to both U.S. and other international locations.

While we do not believe that a negative catalyst is imminent, we believe this scenario represents a tinder box that could light at any time. For now, we are firmly on the sidelines with Starbucks stock and move our previous buy rating to a hold.

This article was written by

Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: Disclaimer: The information contained herein is for informational purposes only. Nothing in this article should be taken as a solicitation to purchase or sell securities. Factual errors may exist and will be corrected if identified. Before buying or selling any stock, you should do your own research and reach your own conclusion or consult a financial advisor. Investing includes risks, including loss of principal.