How To Outperform Index Funds

Summary

- Passive index funds do one thing right and three things wrong.

- The key to outperformance: copy what commercial index funds do right and don't copy what they do wrong.

- My personal passive index fund performance for the last 5 years.

Wavebreakmedia/iStock via Getty Images

There is no point belaboring the well-documented and the obvious: passive index investing almost invariably outperforms other investment approaches. But here's the surprise: it does not logically follow that anyone should buy and hold commercially-available index funds.

Why? The answer is because most (or all?) commercially available index funds suffer from three intrinsic flaws that reduce performance. It stands to reason that if you could replicate the success of passive index investing without any of these three performance-destroying flaws, outperformance should come naturally over the long term.

Flaw Number One: By definition, market cap-weighted funds buy more shares of a stock when the market cap is higher and fewer shares when the market cap is lower. All things being equal, market cap rises when the stock price rises and falls when the stock price drops. The inescapable conclusion: cap-weighted funds purposefully buy high and sell low.

It's not terribly difficult to see why buying high and selling low might reduce investment performance. The simple solution to outperform cap-weighted indexes: don't weight the index holdings according to anything related to stock prices. And indeed, many commercial index funds do precisely that - for example, you have equal-weight indexes such as the Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF (RSP), or earnings-weighted indexes such as the WisdomTree U.S. LargeCap ETF (EPS).

This leads us straight to the next fundamental flaw of commercial index funds.

Flaw Number Two: Commercial index funds typically rebalance their holdings. By doing so, they inescapably Moore themselves to average performance at best.

With a simple thought experiment, it's easy to see how. Imagine you pick 1,000 stocks at random to hold for the long term. Do that, and it is overwhelmingly likely that the majority of these stocks will deliver average performance - for illustration's sake, let's say that average performance is 10%.

But if you own 1,000 shares, you're sure to have some performance outliers. Some of your 1,000 stock investments will drop to $0 due to bankruptcies and so forth, but here is the key thing - downside risk is capped because none of your stocks can drop below $0. For illustration's sake, assume 10 of your stocks go to $0.

On the other extreme, some of your 1,000 stock investments will deliver explosively above-average performance, and here is the key thing about that - there is no limit to the upside performance on any stock. Assume two of your stocks jump by 1,000% just for the sake of this thought experiment.

Now add up the total performance on the outlier stocks. You've got a loss of 1,000% (100% times 10 shares) plus a gain of 2,000% (two shares soaring by 1,000% apiece) leaving you with a total performance of 1,000% on all of your outlier stocks. Thanks to the 1,000% gain on your outlier stocks, your total portfolio performance will be slightly above the 10% average... On one condition: you must not rebalance.

If you sell shares of your above-average stocks and reallocate capital to your below-average stocks, then there is no theoretical way to capture that extra sliver of 1,000% performance. Rebalance and your total portfolio performance is capped at 10% at best (but could go lower depending on when and at what prices you buy and sell the outlier stocks). By contrast, take no action to reallocate capital, and your performance is highly likely to exceed the 10% average.

So what can you do to outperform equal-weighted or fundamental-weighted index funds? That's easy. Don't do anything.

Flaw Number Three: Most commercially-available funds charge fees. The notional that you can outperform an index simply by copying it and not charging yourself fees requires no explanation.

Conclusion: So how do you beat most broad commercial index funds at their own game? Simple! Pick a diversified portfolio of individual stocks, don't weight the shares according to market cap, passively hold the shares for the long term, do not rebalance or do anything else besides reinvesting dividends, and don't charge yourself fees. Then give yourself five or ten years to see if it worked. It's an approach uniquely suited to individual investors (if you're a professional fund manager, good luck convincing investors to pay you doing literally nothing with the portfolios you manage.)

Now, here's a personal anecdote. Let me start by telling you that I am not a professional investment advisor and that I have absolutely zero special expertise or access to information when it comes to investing. I am not unusually intelligent. I am what is technically referred to as "an ordinary, average everyday schmo."

But many years ago, I recognized these three basic flaws with mutual funds and ETFs as potential investment opportunities. I had a profound belief that it is very hard to make money by investing in companies that don't, and figured that I could avoid losses by avoiding companies with sky-high price/earnings ratios, thin (or negative) profit margins, and hefty debt loads. I knew that I wanted to live off of dividend income, so I wouldn't ever need to sell stocks during bear markets, so I gravitated towards dividend growth companies. And like many of you, I lived through both the internet bubble and the financial crisis and felt convinced that the efficient markets' hypothesis (and by extension, many of the investment products it spawned) is baloney. And with that, I bet nearly 96% of my net worth on designing a passive stock index based on these core investment beliefs. It was a gutsy move that absolutely went against conventional wisdom.

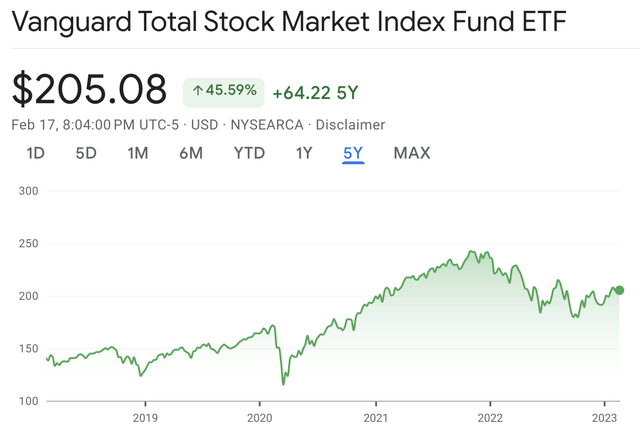

But it worked (or at least it has up to now). According to Google Finance, the five-year performance of the Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) stands at 45.59%, with an annual dividend yield of 1.55%.

VTI Performance (Google Finance)

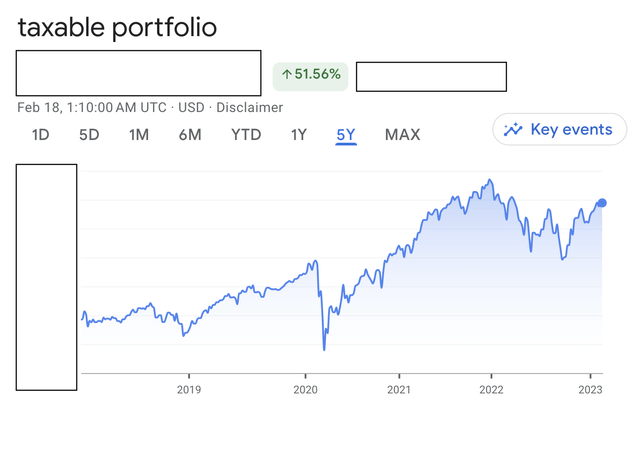

My personal passive index fund, according to Google Finance, delivered capital gains of 51.56% over the past five years, plus an annual dividend yield of 2.66%, for total long-term outperformance of 11.52% (thanks in great part to lower losses during the bear market that started last year).

Taxable Portfolio Performance (Google Finance)

I don't suggest anyone buy or sell any security (including those I own), because I am not licensed or qualified to make any such suggestion. What I do suggest is that the standard thinking about index funds is really just a sales pitch. Not only is it possible to do better, but it is reasonable to expect that you could do better.

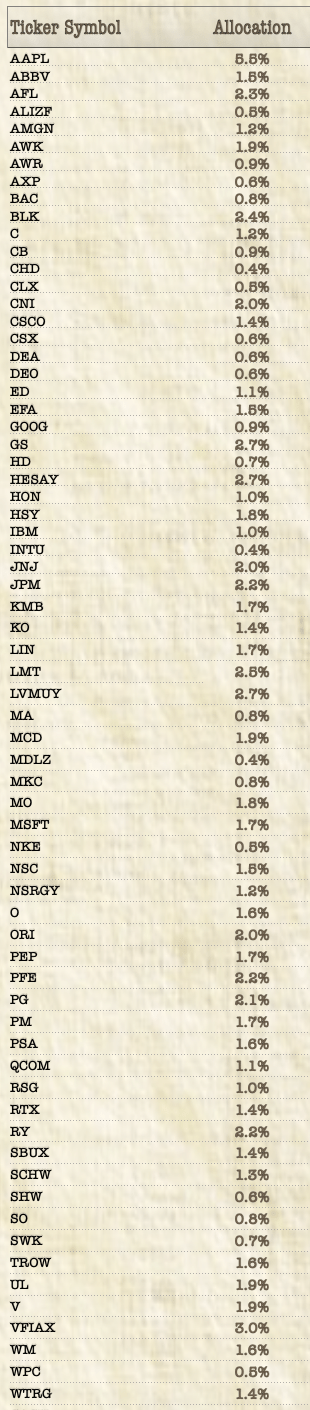

As I've been doing for years for disclosure purposes, here is my entire portfolio and portfolio allocations:

Portfolio Positions and Allocations (Author's personal spreadsheet)

This article was written by

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of VFIAX either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: I have long positions in every security listed in the attached spreadsheet and no other financial positions besides those. I am not an investment advisor and nothing contained in this article is investment advice. I cannot guarantee the accuracy of any calculation used or cited in this article. This article is written for one reason and one reason alone: entertainment value.