Bridger Aerospace Isn't Worth A Flyer

Summary

- On its face, BAER looks attractive, with a reasonable valuation and a growing end market.

- But the balance sheet is much worse than a cursory look reveals, and cash constraints threaten near-term growth.

- Like other low-float de-SPACs, Bridger stock may see a run or two, but the mid-term outlook for the stock remains negative.

Kara Capaldo/iStock via Getty Images

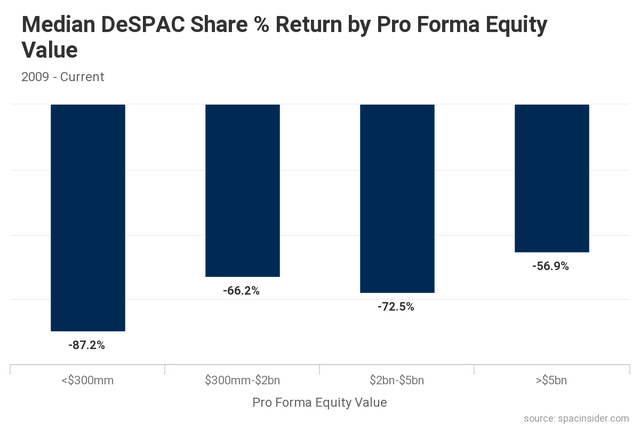

At this point in the trend of businesses going public via mergers with SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies), it would seem like there almost has to be some value somewhere. So-called de-SPAC mergers have been abysmal performers, with the smallest de-SPACs posting the steepest declines:

That performance has made de-SPACs somewhat of a punchline in the investing world, and no doubt led many investors to simply ignore the group entirely. That reputation in turn might (should?) create at least a few opportunities for risk-tolerant, contrarian investors.

But looking at de-SPACs, and particularly the most recent de-SPACs, on an individual basis, that thesis starts to fall flat. Bridger Aerospace (NASDAQ:BAER), whose merger with Jack Creek Investment Corp. closed last month, is just one example.

Admittedly, on its face, BAER stock looks interesting, particularly with the stock already down 60% from its $10 merger price. Valuation as described by the company looks reasonable, and the forest fire-fighting company should have (unfortunately) a growing book of business ahead.

A closer look, however, shows an enormous problem on the balance sheet, and real questions about whether this business can be large enough to be a public company at all. And because of an enormous redemption rate ahead of the merger with Jack Creek, the importance of common equity to overall valuation here is relatively small: the plunging BAER stock price doesn't really make shares that much more attractive from a fundamental perspective.

Like other low-float de-SPACs, there may be some crazy trading here — BAER spiked on Friday afternoon for no apparent reason — but the fundamental story here looks weak. There may be a deep value play somewhere in the de-SPAC group, but Bridger Aerospace doesn't seem to be it.

What Bridger Aerospace Does

Bridger provides fire suppression and surveillance services in the western U.S. As of December, per the most recent investor presentation, the company had 20 aircraft in its fleet, with plans to add another nine this year.

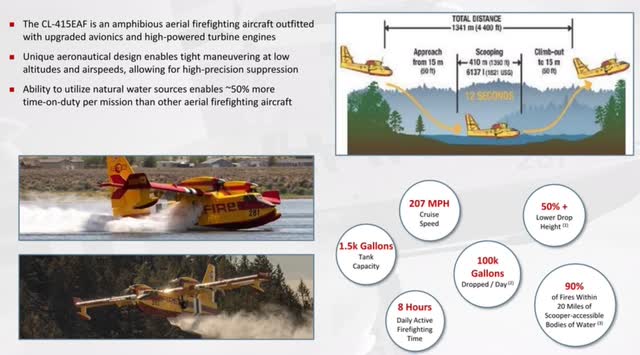

Most of the company's revenue comes from a small portion of that fleet. Bridger operates five CL-415EAF planes (one more should be delivered this year), known as "Super Scoopers". (In 2021, Business Insider provided a detailed look at those planes.) The model is so named because it can actually "scoop" water from a natural source (like a lake) to refill its tanks:

Bridger/Jack Creek presentation, December 2022

Bridger purchases the planes from a private company (Canada's Viking Air) and has a maintenance subscription as well to meet government requirements. But Bridger is the operator of the planes, hiring pilots, managing refueling, and determining attack plans. That is true for the rest of the fleet as well, which includes 13 aircraft used for surveillance and fire suppression, as well as two drones.

The Bull Case for BAER Stock

Bridger remains a relatively small company at the moment. According to the last amended S-4 before the merger (p. 145), management expects 2022 revenue of roughly $46 million. But there's a runway here for growth.

Bridger itself plans to build out its fleet over time, adding more Scoopers as well as other aircraft. Management argues that the added planes will see strong utilization (see p.147 of the S-4) because a) a customer requesting Scoopers will need as many as are available and b) if conditions are such that one customer is asking for aircraft, it's likely that similar conditions will drive similar requests elsewhere.

That revenue growth in turn should drive a rapid expansion in margins. This is largely a fixed-cost model. Once the planes are purchased and staffed, added revenues, whether through "standby days", in which Bridger is paid simply to be available, or actual flight hours, thus are extremely profitable.

When Bridger and Jack Creek announced the merger in August, they projected revenue to increase from $39 million in 2021 to $106 million in 2023. Adjusted EBITDA was guided to rise roughly 6x on the back of less than 200% revenue growth, with EBITDA margins skyrocketing from 27% to 60%.

Meanwhile, as noted above, there should unfortunately be no shortage of demand. Wildfires are projected to become both more frequent and more intense. In the western U.S., where Bridger currently operates, there is more development in more areas with exposure to wildfires. That in turn increases the potential cost in property (and sometimes lives) and thus the incentive of federal and state agencies to spend aggressively on fire suppression.

Bridger's experience with Scoopers is another potential advantage. A study funded by the federal government last decade found that the aircraft are both more effective and more cost-effective. Yet there aren't that Scoopers many being produced by Viking Air; in fact, production isn't guaranteed past 2025.

As a result, Bridger's small size is actually rather large in the context of a niche capability. And scale will matter: the biggest company (which Bridger clearly plans to be) will be able to acquire the most experienced and most qualified pilots (of which there are few).

The Bullish Valuation

So there's seemingly the potential for a big business here. Perimeter Solutions SA (PRM), which focuses on providing fire retardant chemicals, also went the de-SPAC route. PRM stock hasn't been a huge winner — it trades below $9 — but the company has an enterprise value of roughly $1.9 billion. Including a modest amount of net debt ($113 million at the end of Q3, per the S-4), and using the capital structure delineated in the SPAC presentation (shares outstanding of ~111 million), at Thursday's close of $3.93 Bridger's enterprise value sits at $550 million.

That figure below 10x the updated projection for 2023 EBITDA ($58 million — more on the update in a moment). That's a seemingly attractive model, particularly because capital expenditures here are relatively low. Bridger will spend aggressively on new aircraft, but annual maintenance capex should be relatively modest. That in turn means plenty of free cash flow, which Bridger can use initially to further add scale and, eventually, to provide returns to shareholders.

It's difficult to pin down precisely what the multiple should be, given a lack of direct peers. But PRM trades at ~15x trailing twelve-month EBITDA, and its ~36% margins, while impressive, lag those projected by Bridger. Given similar secular tailwinds (no pun intended), even discounting for higher risk (Bridger is less mature) and a weaker balance sheet, bulls would argue BAER easily deserves at worst a modest discount to PRM. Add multiple expansion to further bottom-line growth beyond 2023, and there's a pretty clear path for BAER to reclaim the $10 merger price and then some in the coming years.

Shares Outstanding

At first glance, I was rather intrigued by the potential bull case. BAER was trading like so many recent de-SPACs — a weird, brief, and illogical post-merger spike, followed by a sharp plunge — yet seemed to have a far more reasonable valuation and a far more sustainable business model.

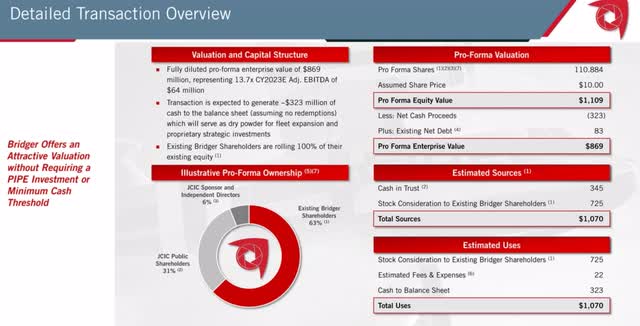

But looking closer, the bull case here has holes. A big issue sits on the balance sheet. Here's how Bridger and Jack Creek detailed the capital structure ahead of the merger:

Bridger/Jack Creek merger presentation, August 2022

As contemplated at the time Bridger would have 110.9 million outstanding shares. That includes 34.5 million shares from shareholders of the JCIC SPAC, 39.6 million from existing Bridger shareholders, and 6.9 million for the Jack Creek sponsor (subject to a series of adjustments depending on how the merger actually functioned). And as a footnote in the slide details, it also includes 29.9 million shares from the conversion of Bridger Series C convertible stock.

Yet, in the Form 8-K filed upon merger close (see the third page), at close Bridger actually had just 43.8 million shares outstanding.

Two factors account for the massive disparity between the pro forma share count described in August (and December) and the actual count in February. The first is that JCIC saw an incredible amount of redemptions. Of the 34.5 million common shares outstanding, 34,245,643 shares were redeemed (per that same 8-K).

More than 99% of SPAC shares were redeemed for cash instead of rolled into the merger. Even by the standards of the sector, where average rates are starting to clear 80%, that's an incredible vote against the attractiveness of Bridger as a merger target.

More importantly at this point, the redemptions leave Bridger in a relatively questionable financial position. At September 30, the company had $94 million in cash on the balance sheet. It expects to spend $133 million total in 2022 and 2023 on capital expenditures, including aircraft purchases. But it's only spent ~$32 million through the first three quarters of 2022.

In other words, the remaining capex budget through the end of 2023 is ~$101 million — more than the company's cash on hand. That's a problem considering that the business posted negative operating cash flow in the first three quarters of 2022.

Bridger either has to pull back on its capex plans or raise capital. The latter option is exceptionally difficult: the company actually has a market cap of just $172 million at Thursday's close, meaning any significant capital raise would dilute shareholders and tank the BAER stock price. The former seems more likely — but that in turn means the projected EBITDA growth from ~$4 million in 2022 to ~$58 million in 2023 simply isn't going to happen.

The Preferred Stock

Redemptions are the problem. The preferred stock is another.

The pro forma share count in the merger presentation assumed the preferred stock would be converted into common stock. But with the conversion price at $11 — nearly triple Thursday's close — that's not going to happen. And without conversion, the preferred stock (Series A after the merger) may be called preferred stock, but in practice is actually debt.

After all, the Series A preferred stock has a liquidation preference, giving it claim to any assets should the business wind down. It receives dividends, paid in kind (through an increase in that liquidation preference), which mimic paid-in-kind interest on debt. If Bridger is sold, the liquidation preference is paid off in full, just as convertible bonds would be in a similar scenario. And, most importantly, the preferred stock must be redeemed in April 2032 — akin to a maturity date for corporate debt.

For all intents and purposes, the liquidation preference (which at this point should total ~$340 million) should be treated as debt. It's high-interest debt as well, with a rate of 7% until April 2028, 9% for the following 12 months, and then 11% from that point onward.

Accounting for the preferred stock, then, Bridger's enterprise value is $625 million ($172 million market cap + $113 million traditional debt net of cash + $340 million preferred stock). That's notably higher than the merger presentation would suggest with BAER trading near $4.

A Tough Bull Case for BAER Stock

$625 million is a nearly 11x multiple to the $58 million in projected 2023 Adjusted EBITDA. That seems nowhere close to attractive, let alone compelling.

After all, Bridger already has cut its projections for both 2022 and 2023 since the merger was announced. The sharply lower 2022 outlook ($39 million in August, $4 million in December) was attributed mostly to a weaker-than-expected fire season, and on that front management appears to be telling the truth. Perimeter Solutions posted a double-digit decline in revenue through the first three quarters of 2022 (it hasn't released fourth quarter results yet, but that quarter is seasonally quiet). Again, this is a fixed-cost model, so revenue movements have a huge effect on the bottom line — in both directions.

The 2023 movement is far less significant, coming down only about 10%, but there are worries there as well. Margin projections have already been pulled down about three points on essentially flat revenue, suggesting higher-than-expected costs (perhaps from public company expenses). And, as noted above, it's not at all clear that Bridger is going to be able to fund the aircraft expansion that was supposed to underpin that growth. At the very least, the company probably has to pull back heading into 2024; the capital that was supposed to be raised in the merger.

Even the multiple is not necessarily that attractive. Yes, PRM trades at 15x — but that company generates revenue from fire season no matter who is flying the planes. Bridger has to win the contracts itself — and it only has a few. In fact, in the first nine months of 2022, one customer — which appears to be the US Forest Service — accounted for 97% of revenue. In 2021, the USFS generated 74% of total revenue.

In the presentation, Bridger and Jack Creek cited contractors like Kratos (KTOS), AeroVironment (AVAV), and Mercury Systems (MRCY) as peers, and noted that those businesses generally received mid-teens EV/EBITDA multiples. But those 'peers' are far larger, and importantly far more diversified, than Bridger. The USFS is not a lock for renewal (the service has one-year options on the existing contracts); the agency's 2018 budget, for instance, did not include Scoopers at all.

DLH Holdings (DLHC) is a government contractor in a very different space, but one that has similar (if far less pressing) concerns about revenue concentration with key agencies, and a leveraged balance sheet as well. I'm long the stock, so I believe it's attractive, but shares trade for roughly 8x EBITDA (pro forma for a recent merger). That kind of multiple seems more appropriate for BAER at this point in its maturity than the mid-teens multiple assigned established businesses like Mercury (in particular).

Fundamentally, then, BAER is trading at a questionable multiple to a very questionable EBITDA projection. It already is facing cash concerns which may limit its expansion plans and threaten the growth needed at this valuation.

Again, it's possible BAER goes nuts as "traders" once again target these heavily-redeemed, low float names for a quick game of musical chairs. But for investors, Bridger stock is a no-go.

This article was written by

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of DLHC either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.