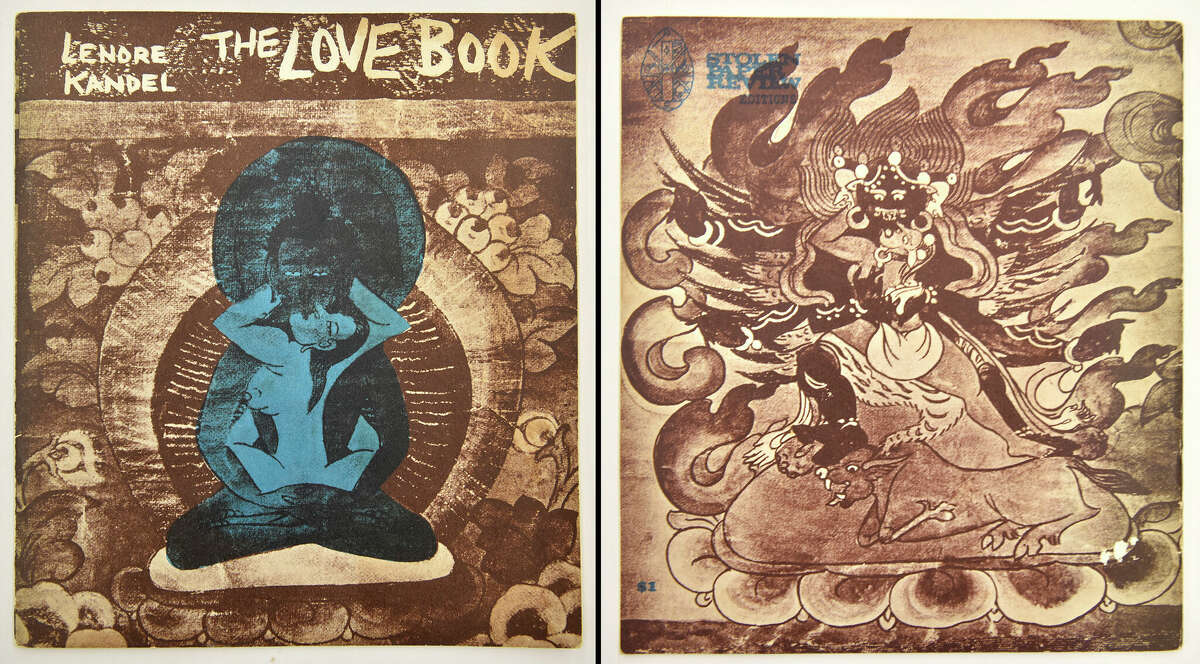

A side-by-side view of the cover and back page of Lenore Kandel's once-controversial work "The Love Book."

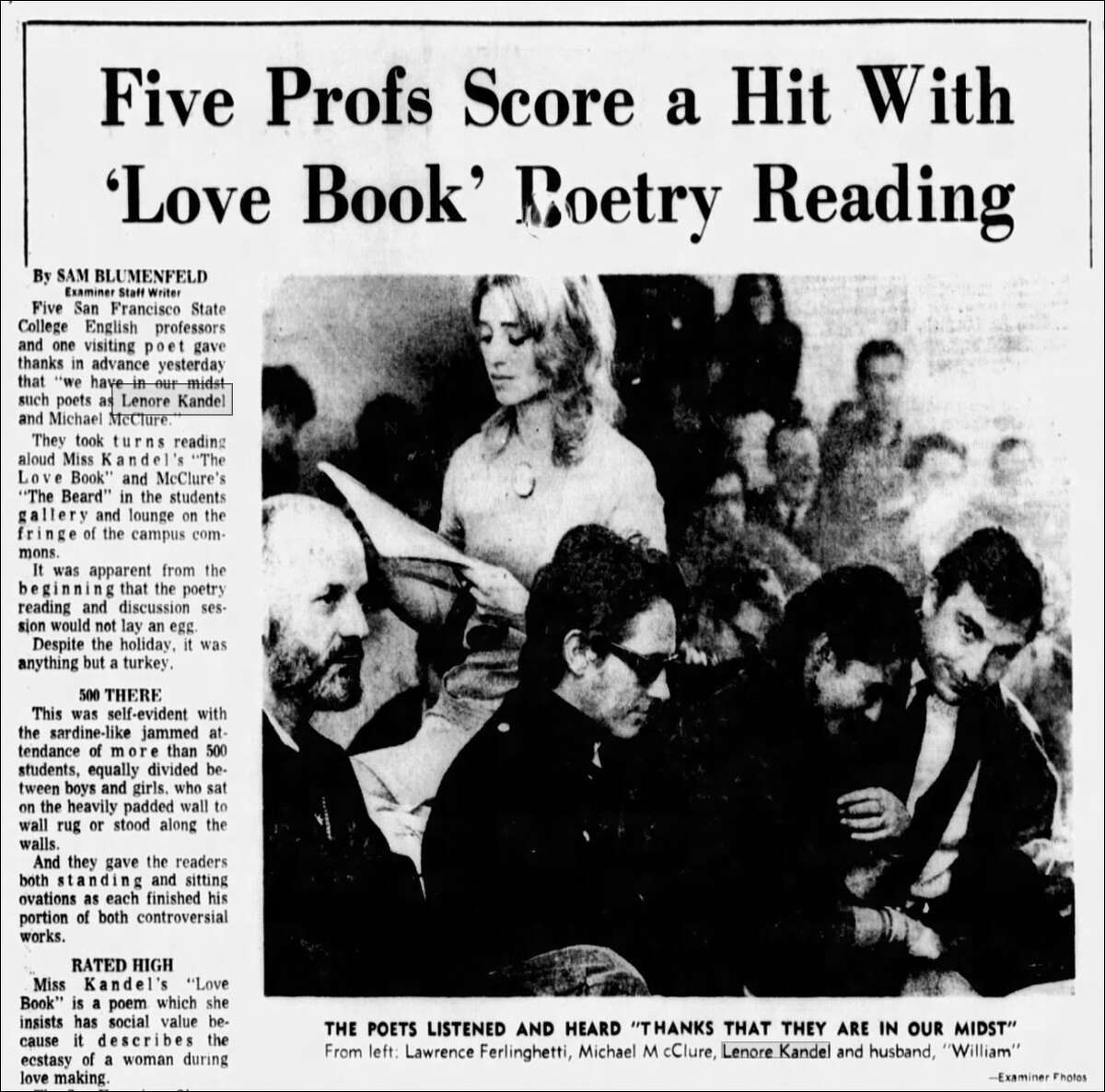

Charles Russo/SFGATEOn an unseasonably warm afternoon in late November of 1966, hundreds of San Francisco State University students jammed shoulder-to-shoulder on the campus commons, enraptured by a handful of English department professors who took turns reading passages from an 825-word book of erotic poetry.

Just a few weeks prior, Lenore Kandel’s “The Love Book” had barely sold any copies. Then it was discovered by San Francisco’s obscenity squad, a police officer duo who raided local shops and entertainment venues to prevent the public from watching or reading about subjects they deemed to be scandalous. Their punitive response, which eventually led to a weekslong obscenity hearing, ultimately caused Kandel’s book to skyrocket in popularity.

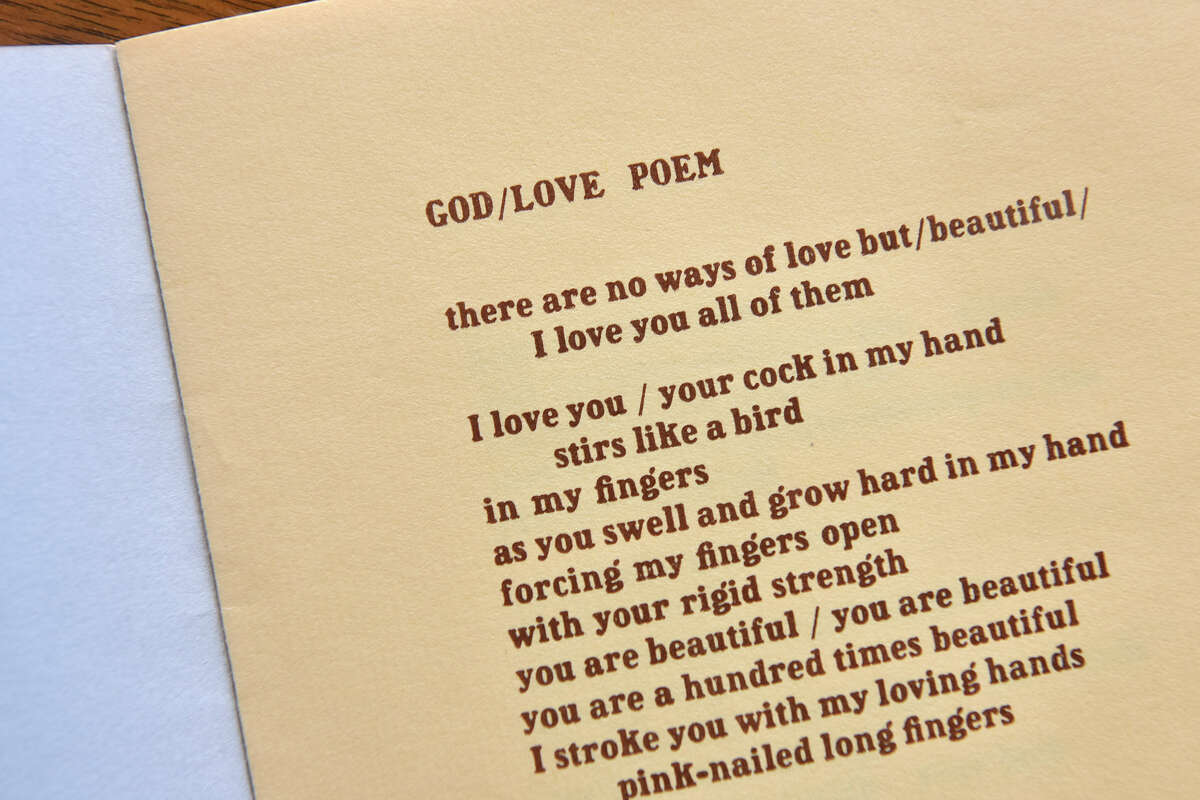

Some of the offending passages from “The Love Book”?

“I am naked against you and I put my mouth on you slowly / I have longing to kiss you and my tongue makes worship on you / you are beautiful.”

Later, Kandel exclaims, “I kiss your shoulder and it reeks of lust / the lust of erotic angels f—king the stars / and shouting their insatiable joy over heaven.”

Bay Area poet Lenore Kandel at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley, on Oct. 1, 1978.

OpenSFHistory - Greg Gaar / wnp73.2383.jpgThe last poem in the collection descends into a post-coital haze. “We are transmuting / we are as soft and warm and trembling as a new gold butterfly / the energy indescribable / almost unendurable / at night sometimes I see our bodies glow.”

Kandel sticking the “F-word” in close proximity to mentions of angels and deities was a step too far, a sacrilegious decision, in the eyes of officers Peter Maloney and Sol Weiner, who confiscated copies of the book from the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street (where Slice House is now) and City Lights bookstore. They subsequently arrested the booksellers on charges of peddling obscene content; the cops also derided the book as “hard-core pornography” and sought to get it banned, believing, perhaps on a deeply personal level, that it “excited lewd thoughts.”

But to Kandel, a writer and student of Zen who straddled both the Beatnik and hippie eras, her poetry was describing the act of sex as a sacred and holy experience between people who were in love. Notably, this was presented from the perspective of a woman with a candidness that was considerably ahead of its time. Even the November 1966 reading and lecture at San Francisco State — while supportive in theory of Kandel’s work — grew contentious at various points, as the all-male panel of faculty argued among themselves about the meanings of pornography and obscenity.

“So much has been said already that anything I say will be an anticlimax,” Kandel joked an hour into the demonstration, causing the crowd to break out in laughter. “I’m very happy that there are different points of view because things are being talked about that haven’t been talked about for far too long a time.”

An excerpt from Lenore Kandel's "The Love Book."

Charles Russo/SFGATEKandel proceeded to defend her work — particularly the “four-letter Anglo-Saxonisms” that police had lambasted as vulgar — and booksellers including Lawrence Ferlinghetti vowed to stand by her too, keeping “The Love Book” stocked on their shelves.

“They were the correct words to use,” Kandel said. “If I had chosen to use euphemisms, of whatever level … whether I said ‘screw,’ ‘ball,’ ‘intercourse,’ ‘penis,’ or any other word … I had to use the word that was both emotionally and poetically correct. And I feel that I did.”

A ‘lusty lewd literary hassle’

Kandel moved to San Francisco in 1960, becoming a member of legendary counterculture groups like the Diggers and the Artists Liberation Front. She lived with her husband, Bill “Sweet William” Fritsch — whom you might call her muse in “The Love Book” — in a North Beach apartment on Chestnut Street that was decorated with beaded curtains she had sewn herself. Kandel was admired and respected by a number of prominent artists. She collaborated with the underground filmmaker Kenneth Anger and the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger in the experimental short “Invocation of My Demon Brother,” where she is seen smoking out of a skull. She also befriended author Jack Kerouac, who immortalized her as the character of Romana Swartz in his 1962 novel “Big Sur.”

The first thing Kandel did upon arriving in the city was drop a handful of her poems on the desk at City Lights. “The Love Book,” however, was considered fairly obscure upon its 1966 release. Only about 100 copies were sold before Maloney and Weiner of the obscenity squad caught wind of it, and police raided stores stocking the book, which went for $1 a piece.

Lenore Kandel and Marty Canter sipping coffee in a Hollywood coffee house in Los Angles on Nov. 12, 1958.

Ed Widdis/APMaloney and Weiner, who said they were responsible for patrolling about 25 bookstores, eight arcades and 10 movie theaters, claimed to have been making their usual rounds when they chanced upon the book at the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street on Nov. 15, 1966. After reading the book and discussing its content with Maloney, Weiner purchased a copy from Alvin I. Cohen, a 26-year-old poet and clerk who was working the afternoon shift. After bringing in two other officers, Weiner informed Cohen that he had violated California anti-obscenity code and was under arrest.

During what the Examiner described as a “lusty lewd literary hassle,” police snatched up a stack of about a dozen other copies of “The Love Book” displayed on the center table in the shop. Jay L. Thelin, the 27-year-old owner, was also arrested on charges of possession, sale and distribution of obscene material. James A. Helms, a 21-year-old customer browsing the shop at the time, was taken into custody after throwing a punch at patrolman Leo McGuire, whom Helms said had forcefully shoved him and several other customers out of the shop when the raid began. Within an hour, a protest broke out, and people marched around the front door with picket signs that read “Fascist police” and “Ban the Bible.” (You can take a look at some of the footage in SFSU's archive.)

Later that week, police raided City Lights, too. Maloney purchased “The Love Book” and arrested the clerk who sold it to him; this time, it was 31-year-old Ronald Muszalski, who claimed he immediately recognized the plain-clothed Maloney when he requested a copy, and cheerfully asked if he wanted enough books for the whole department.

Kandel herself told reporters she was “really amazed” by the busts, and when they asked whether she thought any four-letter words were dirty, her response was succinct.

“Yes,” she told the Chronicle. “Bomb and hate are two of the worst. The war in Vietnam is an obscenity, my poetry isn’t.”

‘I would enjoy seeing it burned’

Next came a five-week case, which went to trial in April 1967, just before the Summer of Love. Kandel read her book aloud to the 10-person jury and reiterated her assertion in the book that sex was a religious act. She made references to other examples of sexuality in religious texts, noting, “I do not feel the nature of man could be anything but religious,” she said. “The body is the temple and a man and woman joining together in love transcends beyond what is the body to the divinity of the holy spirit.”

An article from Nov. 24, 1966, covering a local reading of Lenore Kandel's "The Love Book" with notable poets in attendance, including Michael McClure and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Screenshot via Newspapers.comShe was asked by Assistant District Attorney Frank Shaw to break down each poem line by line and explain what they meant. The Examiner reported that Shaw became “visibly irritated” by some of Kandel’s answers, particularly when he asked if her use of the word “f—k” was a noun or a verb.

Her response was that it could be both. He asked if that violated rules of grammar. “Poets,” she responded, “are not restricted to grammar.”

Not everyone saw eye to eye with Kandel. Dr. Louis Vuksinick, a 33-year-old psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Hospital and a prosecution witness, likened the message of “The Love Book” to “an animalistic type of sexual release.” Gail Potter, a freelance writer and former teacher at Dominican and Golden Gate colleges, who also served as a prosecution witness, said of the book: “I would enjoy seeing it burned. Even if it were burned I believe the fumes would pollute the air.”

But Kandel found a number of unlikely allies, including Nina Beggs, the wife of Rev. E Larry Beggs, a minister at the Congregational Church of San Mateo. Nina said she enjoyed “The Love Book” so much she encouraged her husband to read it as a handbook on sex from a woman’s point of view. The poems, she testified, “reinforced my knowledge that women can and do feel this way, and also that it is good and joyful to do so.”

Rev. Harry Barron Scholefield likewise called Kandel’s work “wholesome” and “creative” and “vastly superior to many other types of stimuli to which we are subject.”

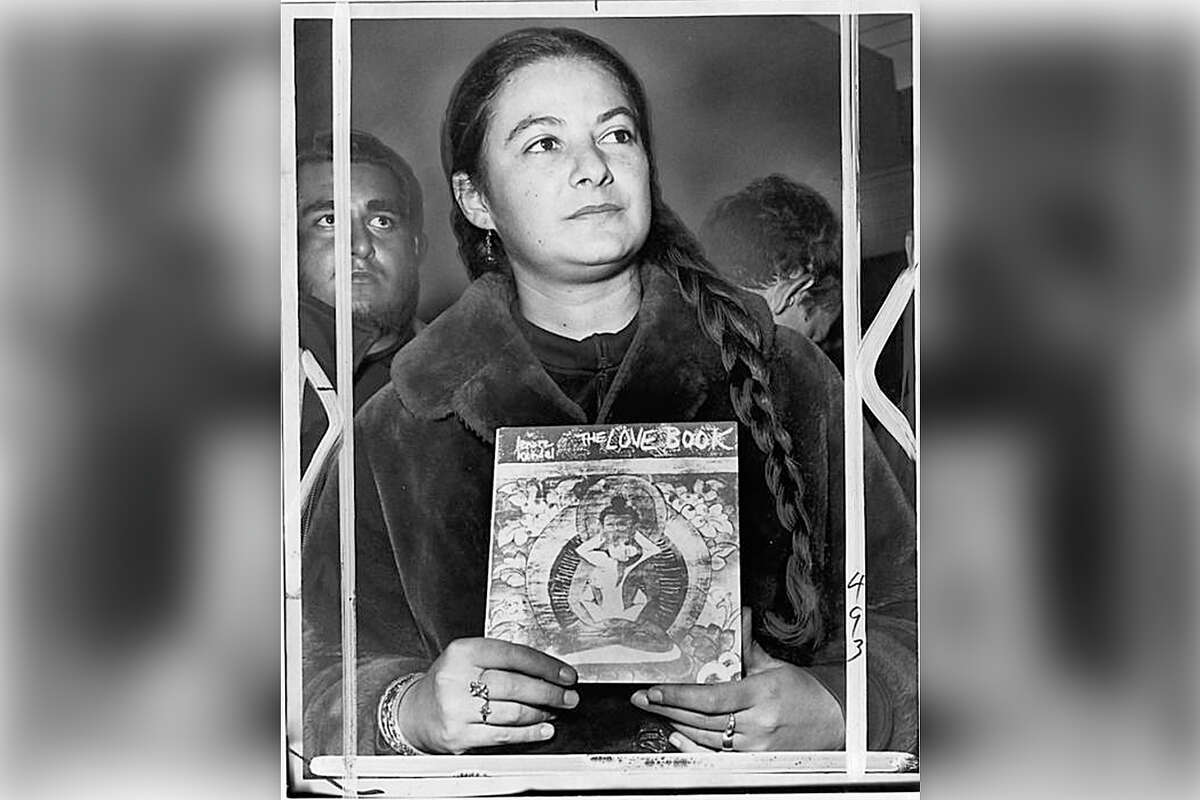

Lenore Kandel holds a copy of "The Love Book."

Fair Use via WikiCommons; Graphic by SFGATEAfter 10 hours of deliberation, the jury returned a guilty verdict, ruling that “The Love Book” was obscene. The booksellers faced maximum possible sentences of six months in jail and a $500 fine each. “It was unanimous from the start that none of us felt ‘The Love Book’ had any social importance,” the jury foreman, a Muni driver named Edward Johnston, told the Examiner.

Kandel was distraught but believed the decision would be reversed. “The truth will come out and prevail,” she said.

She was right — the verdict was overturned on appeal in 1971.

‘A breakthrough work of poetry’

As media coverage of the arrests and subsequent trial spread, sales of “The Love Book” soared to nearly 20,000 copies. Jeff Berner of the Stolen Paper Review, which published the book, said he had received orders from Los Angeles, London and Paris, and promised to donate 1% of the proceeds to San Francisco’s Police Retirement Association.

“This is my way of saying thank you to the police for making ‘The Love Book’ internationally famous,” he said during a press conference in the Psychedelic Shop. He noted that it wasn’t a sarcastic gesture. “My point is to illustrate that censorship is not only evil but self-defeating.”

Kandel went on to write another book of poetry, “Word Alchemy,” and her work appeared in anthologies such as “Poetics of the New American Poetry.” She also read from “The Love Book” at the Human Be-In during the Summer of Love, which continues to resonate with readers.

“It’s a breakthrough work of poetry, because it was the first time we saw a modern American poet, a poet who was a woman, who was willing to talk completely openly and enthusiastically about sex without any inhibitions,” Gerald Nicosia, a post-Beat poet and author of the Jack Kerouac biography “Memory Babe,” told SFGATE recently. “In the 1960s, it was almost unthinkable. It took great courage for her to do that. She was a real poet, and a real poet doesn’t hold back anything.”

Nancy Peters, a publisher, writer and co-owner of City Lights, said that when she began working there in 1971, she was surprised to learn the store had been busted for selling “The Love Book.”

“The text itself is really terrific — strong, sensual, honest, and it was wonderful to see it become so popular and influential,” she told SFGATE in an email. “... I know that Ferlinghetti (along with [Allen] Ginsberg, and other Beat writers) admired her poetry.”

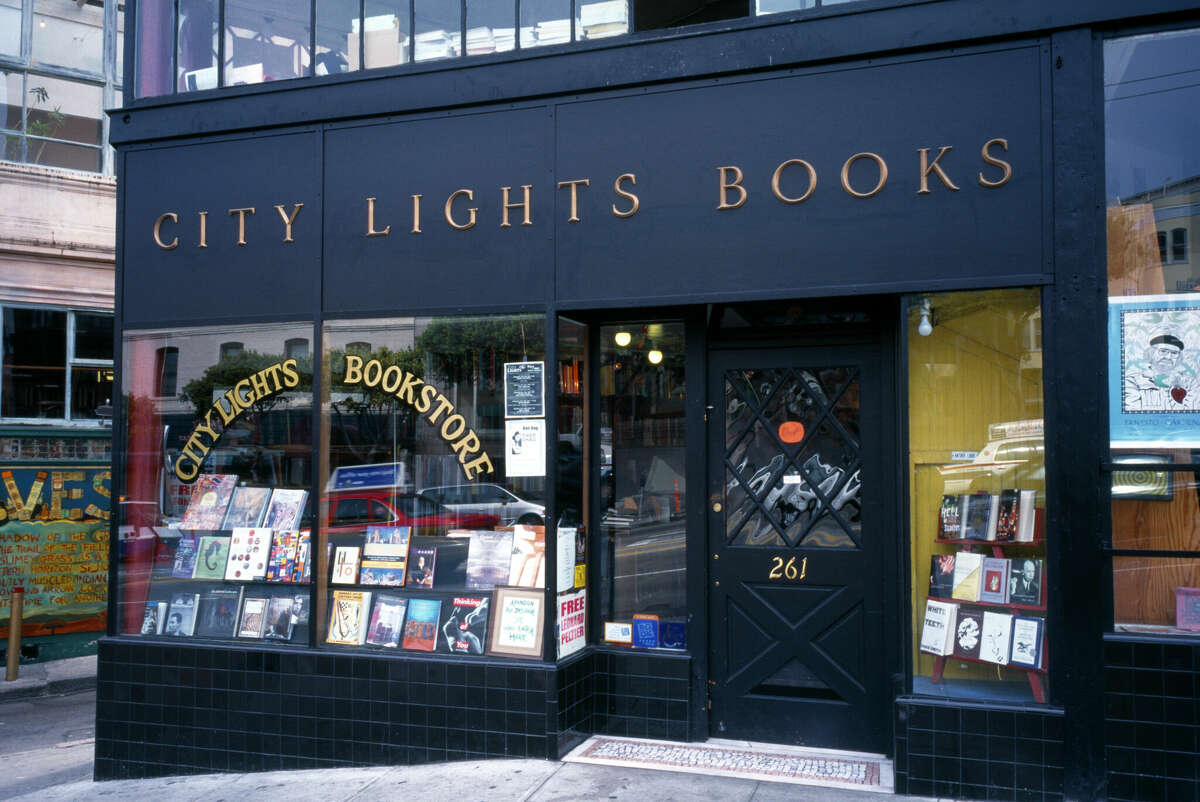

City Lights Bookstore on Columbus Avenue.

Eye Ubiquitous/Universal Images Group via GettyDespite its success, Nicosia said “The Love Book” eventually became difficult to find — and that Kandel never quite got the recognition she deserved. “[Kandel] was a brief sensation, a flash in the pan, but then there were no more books,” he said. “For years and years, you couldn’t find ‘The Love Book.’”

An injury from a motorcycle accident in the 1970s caused Kandel’s physical health to deteriorate, and Nicosia said it became challenging for her to share her work with the public in the years leading up to her death in 2009. “I knew how much pain she was in,” Nicosia said. “It wasn’t easy for her to come out [to readings] but the poetry was bringing language to the people, and she believed in that.”

Alexander Akin, a co-owner of Bolerium Books in the Mission District, said he stumbles upon a copy of “The Love Book” from time to time — “often from the collections of older countercultural folks who are selling off their stuff.” And Darice Murray-McKay, the former Park Branch librarian at the San Francisco Public Library, said that it was a crucial part of the Haight-Ashbury archive she assembled in 2003, spanning all kinds of counterculture literature and paraphernalia. (All copies are now at the main branch for in-library use only.)

Murray-McKay said people frequently came to the library to read the book; they photocopied it and obsessively discussed it. But in spite of how rare and valuable it was, “The Love Book” was never stolen.

“I thought that was telling,” Murray-McKay told SFGATE. “People realized how important it was for other people to have direct access to it, and left it for the next traveler in town to see, and learn from and touch.”

“Collected Poems of Lenore Kandel,” a volume of Kandel’s work including all four poems from “The Love Book,” is available through North Atlantic Books in Berkeley.