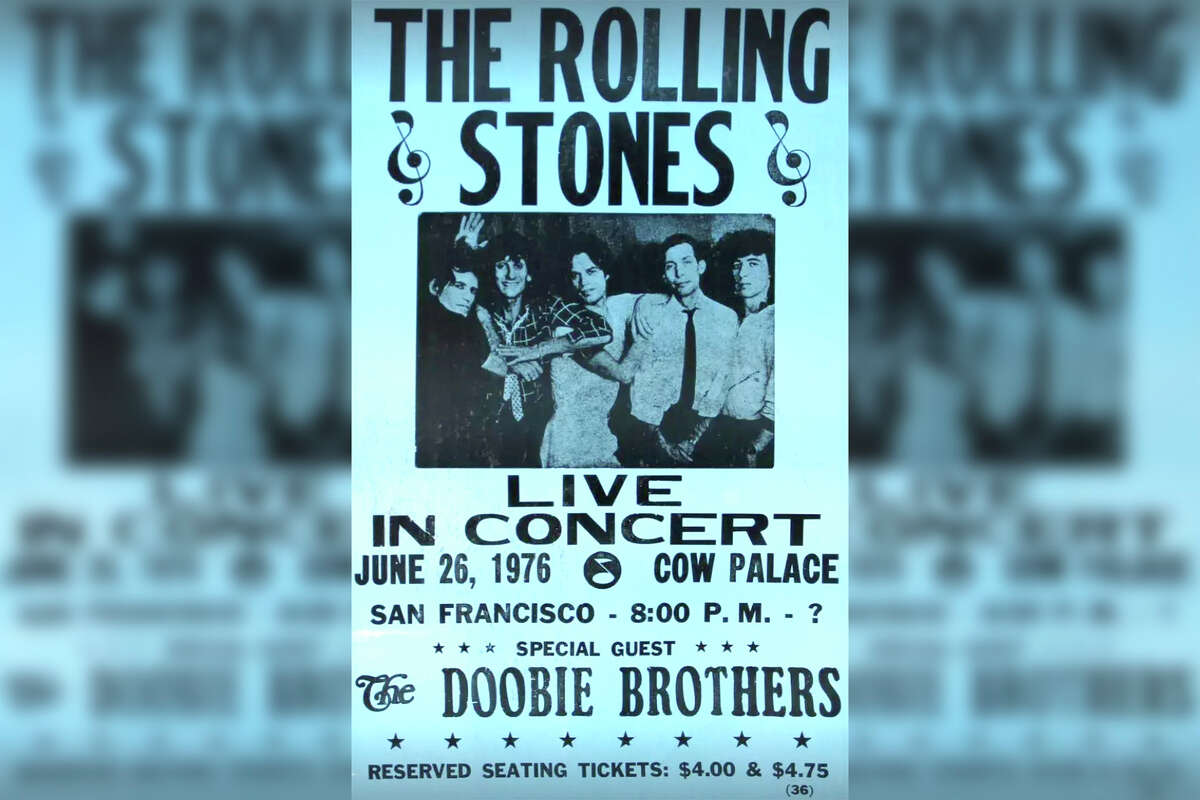

Contrary to what the poster says, the Stones never did play at the Cow Palace in 1976.

Photo illustrationWhen I found out Santa Claus wasn’t real, I felt nothing. Same with the Tooth Fairy. But I’ve rarely felt so betrayed as when I faced the harsh truth that a Rolling Stones concert at the Cow Palace that I thought took place on my birthday never happened.

That’s because 13 years ago, I bought a poster for that very show. As it turned out, that same piece of blue screenprinted cardstock has been selling for years alongside countless other fake and bootleg gig posters, for prices that range from trivial to larcenous.

The poster claims the Stones played at the Cow Palace on June 26, 1976, with the Doobie Brothers as the “special guest.” That would mean one of my favorite classic rock bands played alongside my yacht rock spirit guide Michael McDonald, hours after I was born just 6 miles away.

I didn’t originally look for details of the concert online, perhaps because I was too invested in how I imagined the show to be. Finally, a few years ago a simple web search burst my bubble, but questions about the poster’s origin have haunted me ever since.

Where are these inaccurate mementos of musical history coming from? Who is making them, and why the fake concert date? In my quest to find out, I contacted lifelong industry experts, die-hard poster collectors, music scholars and even the sellers of the fakes themselves.

‘Those are notorious frauds’

My shameful purchase happened during a 2010 visit to New York, when I picked up the Stones poster on a whim for $15 at a souvenir shop, rolled it as best as cardboard does for the flight home, and framed it for my wall.

I didn’t think it was an original from the day of the concert, but the poster, with a smiling picture of Mick Jagger and his bandmates, was just weathered and discolored enough to look 20 years old. And the show details called out to me in the shop like a monkey’s paw.

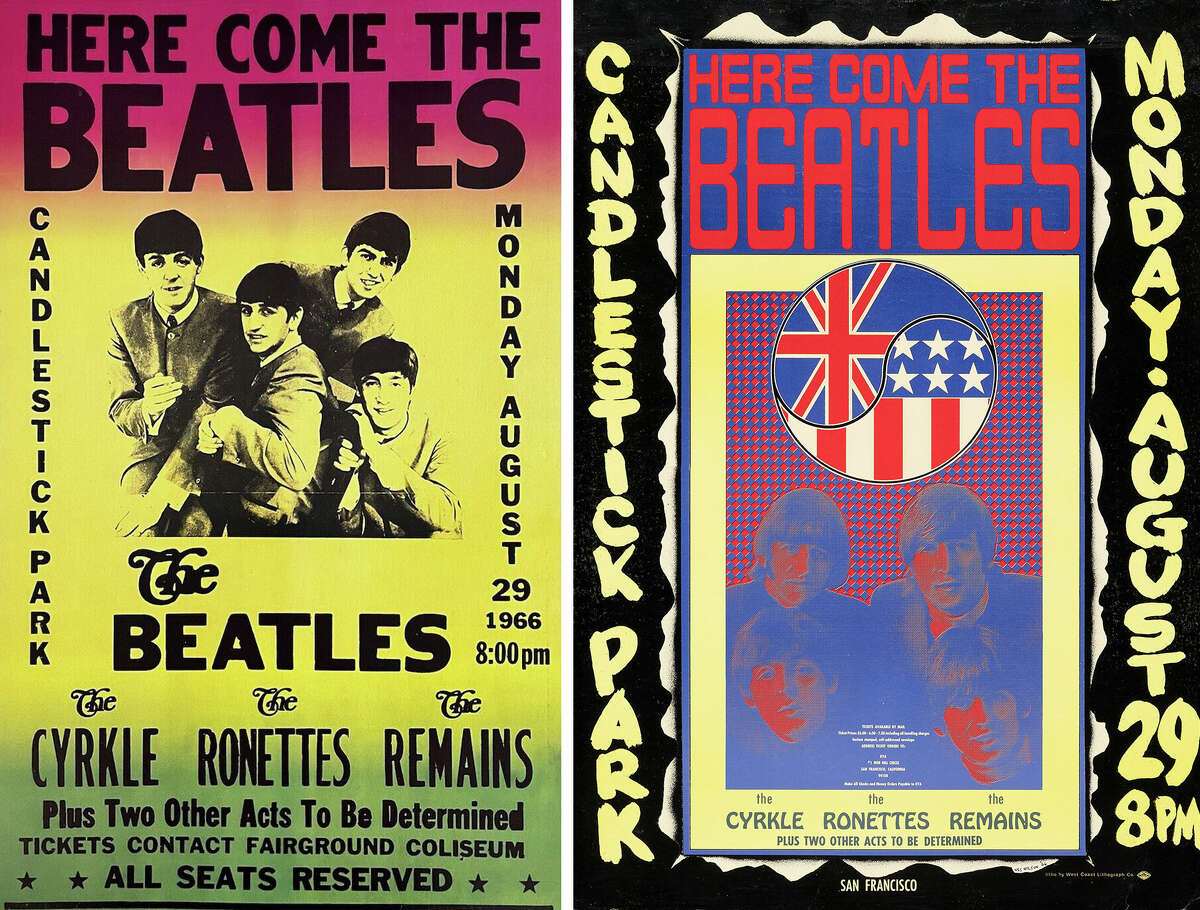

Side-by-side photos of an oft-faked concert poster: the Beatles' 1966 show at Candlestick Park. The poster on the right is the real one.

Heritage AuctionsThis wasn’t some elaborate “White Lotus”-esque con against me. That blue poster has been noted as a fake for years, including on Stones fan message boards and a 2007 blog post noting its appearance in a Bloomingdale’s catalog photo.

But there was some truth to the lie. The Rolling Stones really did play at the Cow Palace — in July 1975, but the Doobies were nowhere to be found. Rather, it was The Meters who opened for them. Jagger and company never played in the U.S. in 1976, charting a European tour instead. (The Doobie Brothers did headline a show at the Cow Palace in May 1976.)

What’s more, that photo of the grinning Stones was actually taken by Annie Leibovitz in 1980. What a fool believes, indeed.

“Those are notorious frauds,” said Nicholas Meriwether, a former Grateful Dead archivist at UC Santa Cruz who is writing a conference paper on fake collectibles related to the band. “They are based on a real poster design. … The one you got rooked by, if you go looking on eBay or Amazon, you’ll find tons of examples of that.”

In retrospect, those posters’ inauthenticity looks painfully obvious, and serious collectors have long scoffed at them, but they’re still widely available in record stores and online marketplaces. A recent search found that same “vintage” Stones poster available for as low as $21.99 on Etsy with a listing declaring that it was “reproduced to look exactly like original” when, of course, there is no original. During my research, a framed copy of it was selling on eBay for $149 and on Amazon for $169. There was another eBay listing for a signed $299 version with the year changed from 1976 to 1965, and after I contacted eBay about it, the listing was taken down. (We archived the link.)

None of the poster sellers we contacted over email for comment for this story responded. Etsy referred us to its policy on vintage items, and eBay referred us to its policy on art sales.

Where it all began

The Stones poster isn’t some one-off concert version of the infamous Bill Ripken obscenity baseball card. Other boxing-style cardboard posters for nonexistent Bay Area concerts in the 1960 and 1970s, with similar block lettering and backgrounds, abound as well.

This includes a $69.99 poster on eBay for a Warlocks concert with Jerry Garcia at Palo Alto High School on Sept. 19, 1964. The Warlocks, who would later become the Grateful Dead, didn’t play their first concert until May 1965 at Magoo's Pizza Parlor in Menlo Park. It leads to some questions that not even the industry veterans and collectors we contacted, who have been doing this for decades, know all the answers to.

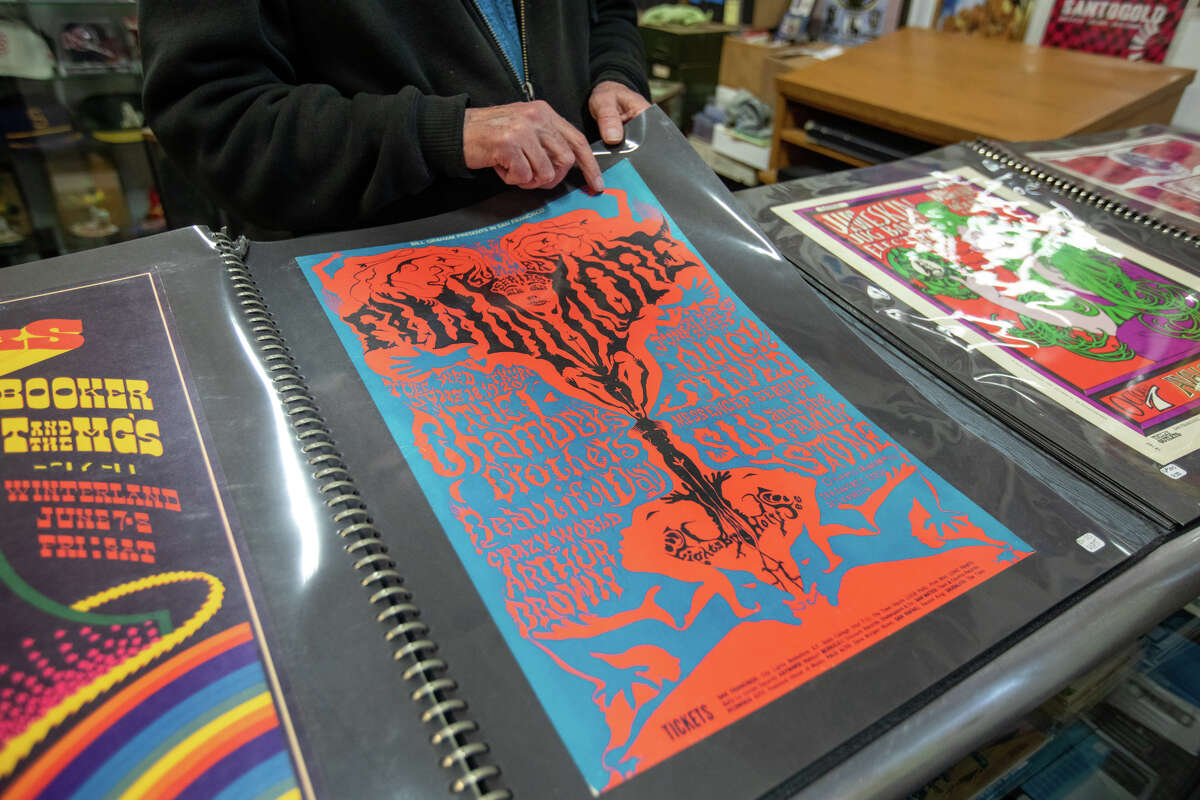

Dennis King, who has operated D.King Gallery in Berkeley selling original concert posters since 1977, told me he first remembers seeing cardboard fakes, some with real dates and some not, about 25 years ago when he received a wholesale catalog selling 101 such posters for about $3 each. He noted that each poster had a catalog number in the bottom left corner.

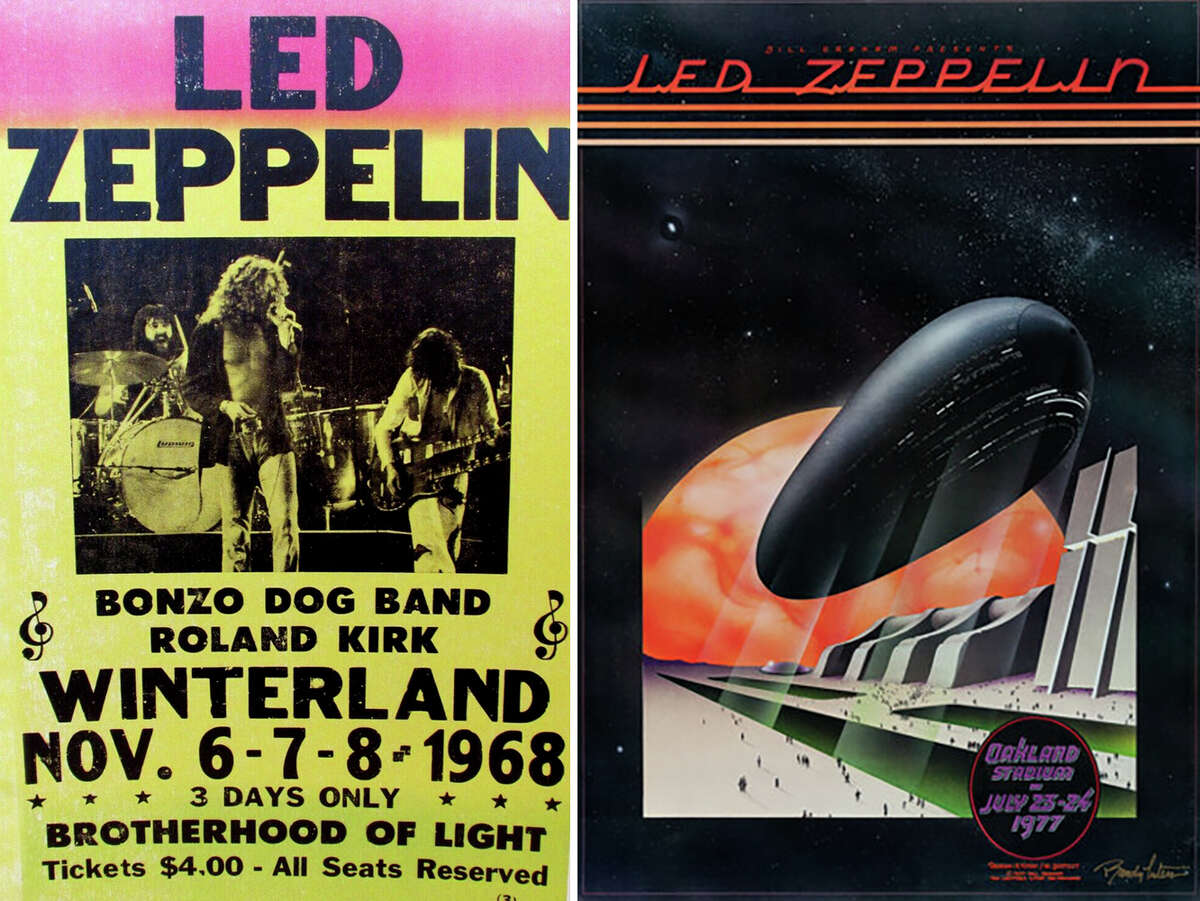

Side-by-side photos of a fake Led Zeppelin concert poster that never happened, left, next to a real one for their 1977 concert at the Oakland Coliseum.

Heritage AuctionsThese low-rate fakes coincided with a boom in the value of original advertising posters for such legendary Bay Area venues as the Avalon Ballroom and Fillmore Auditorium, rising well into the thousands of dollars. This inspired more sophisticated bootleg attempts.

King, who says he’s given legal testimony on the authenticity of disputed posters, said he tried to sound the alarm on the problem with a newsletter he sent to his peers in 1997.

“I sent it out to all the major dealers and collectors I knew, 300 or 400 people,” King said. “I said bootlegs and counterfeits have become a real problem and people can’t identify them. I’m hoping to get cooperation to make sure this doesn’t ruin the hobby.

“You know how many people were willing to cooperate? Zero. No one was willing to work with anyone else,” he said.

A major source of these cardboard bootleg concert posters is Tribune Showprint in Indiana, said Pete Howard, director of concert posters for Heritage Auctions and a decadeslong collector himself. Indeed, Tribune’s name can be found on the bottom left of many such posters online, including listings for the 1976 Stones non-concert.

Howard, whose auctions with Heritage deal in high-end original posters, said he has a form letter he sends to interested sellers who show him concert posters made by Tribune. (Tribune did not respond to a request for comment.)

“They made them strictly to be sold at record stores, flea markets and swap meets,” Howard said. “They’ve been going out there in the world for so many years and decades that they look old now, too.”

Dennis King shows some of the concert posters he has for sale at the D.King Gallery in Berkeley, Calif., on Jan. 23, 2023.

Douglas Zimmerman/SFGATEAs for why a company would make posters with inaccurate show dates, Howard said, “Sometimes I think they make big errors so they can claim to the lawyers, ‘Everyone knows it’s fake.’ But I don’t know how they can get away with this.”

It’s easy to dismiss posters like Tribune’s as cheap, harmless nostalgia, where the rookie mistake like mine of falling for a fake concert date or inauthentic merchandise poster can be laughed off. Serious collectors such as Matt Lee, who has a Rolling Stones memorabilia collection noted by Guinness World Records, have spent great sums of time and money into learning how to tell real from fake.

“I always get people messaging me saying, 'look what I found' thinking because I pay $5,000 to $25,000 for 1960s posters I will want a poster they find for $10 in a tourist tat shop for the same money,” Lee told me via Instagram message.

The harm comes when online sellers, sometimes highly rated ones, advertise cheap items for exorbitant prices. One cursory sweep last week on eBay revealed a Tribune Woodstock poster advertised for $1,235 (the listing has since ended).

And that’s before we get into more sophisticated poster fakes, generally for concerts in the 1960s and 1970s when there were fewer prints made, where not even experienced collectors always agree.

What is real?

What separates real from not real isn’t necessarily where it was made, but when it was made. An advertising poster, which counts as a poster that was sold before or at a concert, has premium value in the collecting world. This includes Fillmore concert posters printed by Bay Area promoter Bill Graham, which sold for under a dollar at the time.

But Graham also reprinted those same concert posters after the shows ended. Those are defined as merchandising posters and carry a fraction of the originals’ value in the collecting world (though they can still sell for hundreds of dollars). Then there are pirated posters, where a third party reprints a concert poster using the same plates but doesn’t hide their source, and outright fakes meant to pose as originals.

Many of the most commonly faked concert posters involve real Bay Area shows. Howard, who lives in San Luis Obispo, said one prime example is the Beatles’ final live concert, in August 1966 at Candlestick Park. An original cardboard poster in near-mint condition sold on Heritage for $32,000, he said, while a reproduction of the same poster would only go for $50 to $100.

“You have to know just what to look for,” Howard said. “It’s caveat emptor to the max,” referencing the Latin phrase that essentially translates to “buyer beware.”

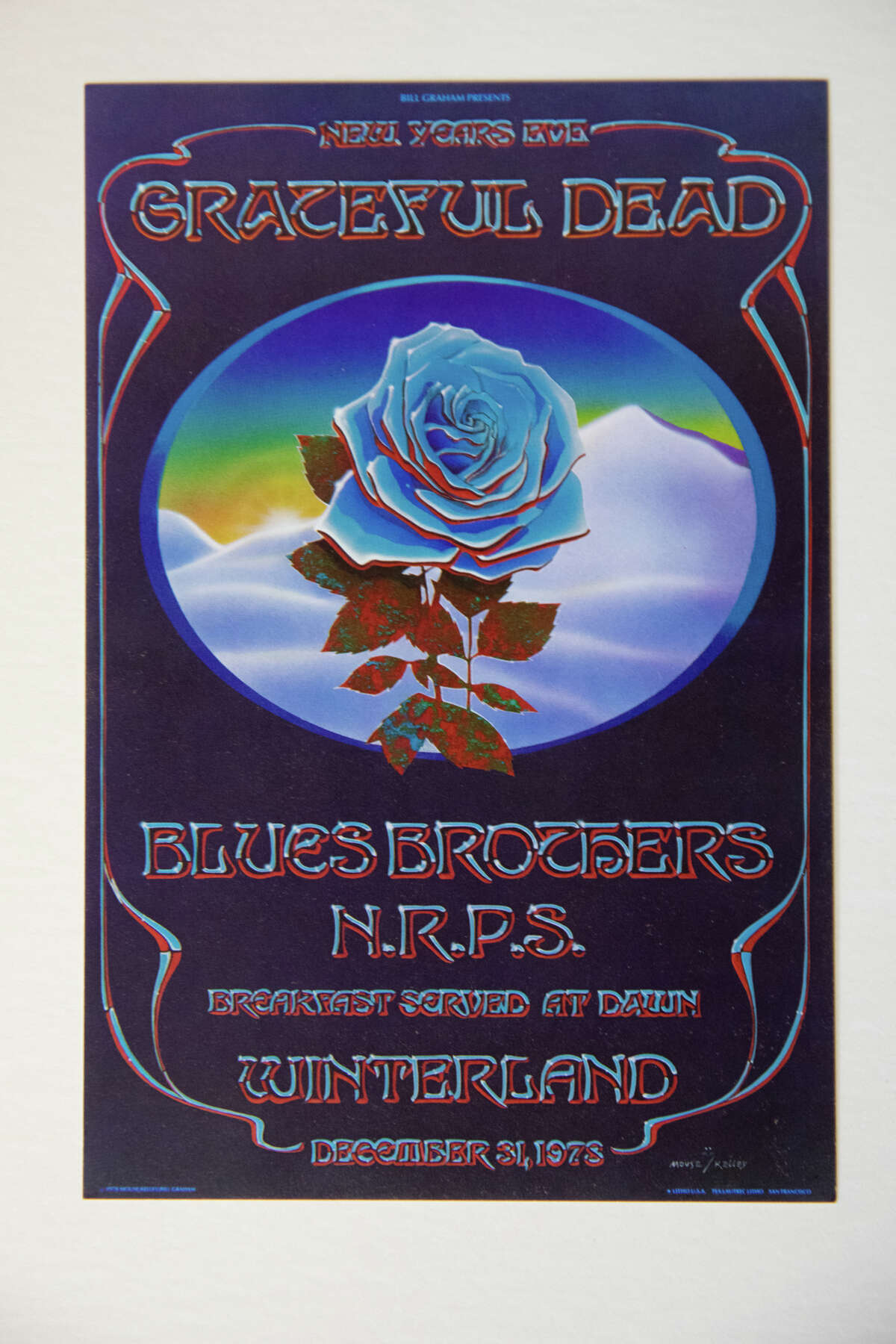

Mike Storeim, who has been collecting concert posters since the early 1980s and operating his online store since 2000, counts two Bay Area shows among the top five fakes. One is the “blue rose” poster for the closing of Winterland featuring the Grateful Dead on Dec. 31, 1978, and the other is for Led Zeppelin’s 1977 concert promoted by Bill Graham at the Oakland Coliseum.

Storeim told me the Winterland poster was faked by someone who took a photo of the original, which detracted from the color and clarity. He said he started seeing the fakes take off in the 1990s, and that only half the Winterland posters he is offered are real. He estimates an even higher percentage of the Zeppelin posters are fake.

The original poster of the closing of Winterland, with the Grateful Dead and Blues Brothers, at the D.King Gallery in Berkeley, Calif., on Jan. 23, 2023. The poster is often bootlegged.

Douglas Zimmerman/SFGATEAnother oft-forged poster involves the most famous image ever made for the Grateful Dead — Edward Joseph Sullivan’s “skeleton and roses” drawing used for their Family Dog show at the Avalon in September 1966. Meriwether said original prints routinely sell for up to $50,000, and Storeim posts that he once sold a 9.9 condition copy for $116,150.

Spotting a fake for that poster requires a magnifying glass that can catch a tiny missing credit at the bottom. Dealers and collectors of psychedelic concert posters routinely use Eric King’s guide to look up known forgeries for that Dead poster and many others.

One basic tell for a fake involves the paper it’s printed on, said Grant McKinnon, manager of SF Rock and Posters & Collectibles in San Francisco. McKinnon asserted that nearly all psychedelic art posters in the ’60s and ’70s were printed on vellum, a soft and porous paper that’s more difficult to fake.

“From over 30 years of doing this, at most 10% of the posters I’ve dealt with are cardboard,” McKinnon said. “Most are on paper that can be rolled and cardboard can’t be rolled.”

A common rule of thumb is that a real concert poster won’t include the year. But Howard said that’s a misleading indicator – especially if the concert is in December or January. The aforementioned closing of Winterland poster on New Year’s Eve 1978 does include the year, for example.

Dennis King shows some of the concert posters he has for sale at the D.King Gallery in Berkeley, Calif., on Jan. 23, 2023.

Douglas Zimmerman/SFGATEIt heartened me to learn that even the experts have been fooled. Meriwether said he once spent $50 on what turned out to be a bootlegged edition of the black-and-white poster advertising Jerry Garcia’s solo appearance at the Armadillo World Headquarters show in Austin in 1982.

“I figured it out by asking one of the dealers,” Meriwether said. “He said ‘Yup, you got burned, it’s a fake.’ Live and learn.”

The most polarizing poster

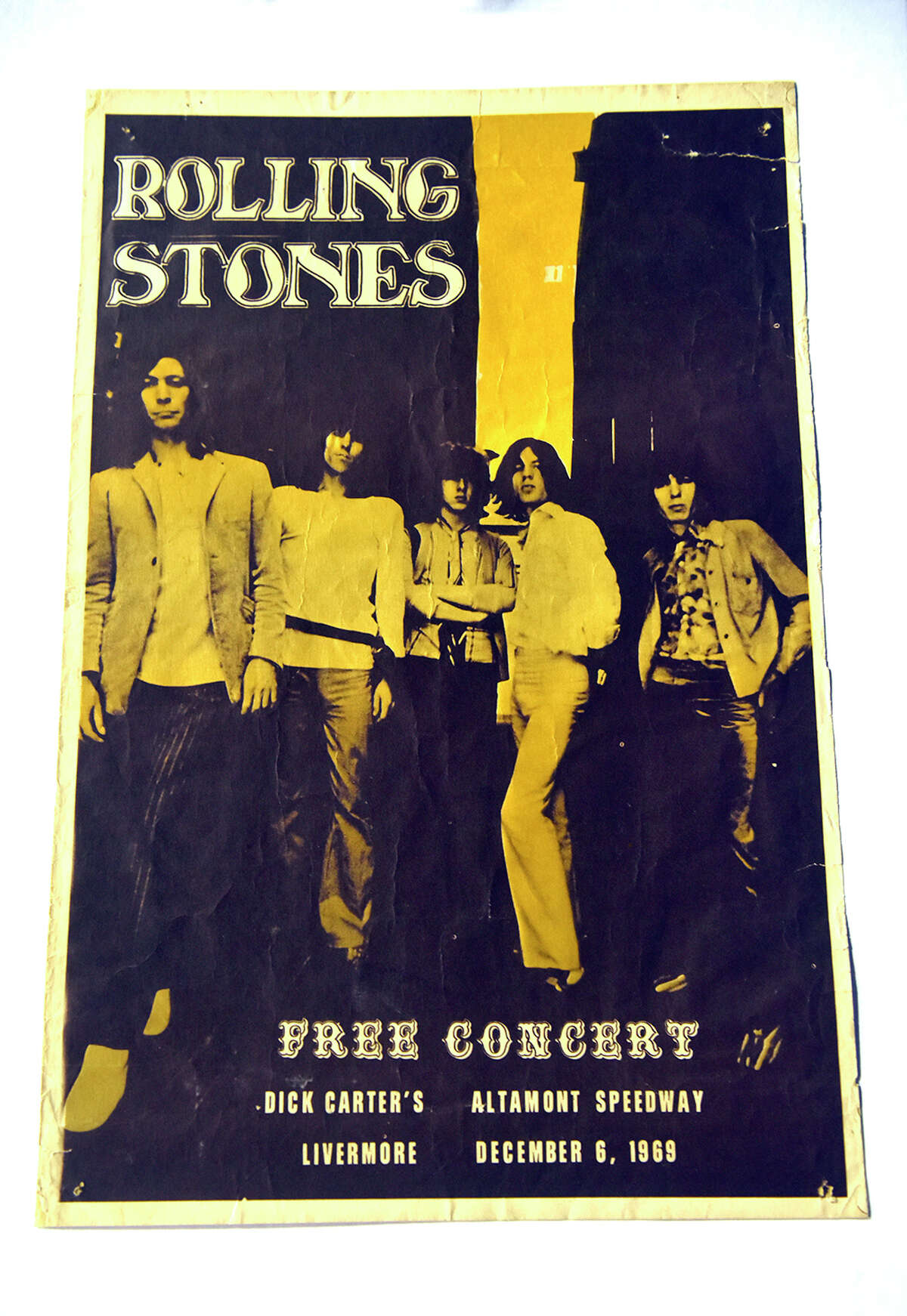

Perhaps nowhere does the line between reality and non-reality blur greater than the most infamous concert in rock history: the Altamont concert headlined by the Rolling Stones on Dec. 6, 1969.

Whether there ever was an original Altamont poster sold before or at the fatal show depends on whom you ask. There is no doubt, however, that an 11-by-17 fake, with a large photo of Jagger and “Security by Hell’s Angels” at the bottom, is ubiquitously sold online as a “vintage” or “rare” piece. In fact, I had to break it to my SFGATE colleague that had one hanging on his wall.

The Rolling Stones Altamont poster displayed at Amoeba Records in San Francisco.

Charles RussoThe Bigfoot among collectors, however, is an alleged Altamont poster printed on vellum paper, with an image of the Stones lifted from a Bill Graham poster for their show in Oakland one month earlier.

Many experts, including King and Storeim, are deeply skeptical that an advertising poster for Altamont ever existed, because it would have been nearly impossible to create one with just one day’s notice after the show was moved from Golden Gate Park.

“I was at Altamont,” King said. “I don’t remember anyone seeing [any posters] at Altamont. No one said they had seen one until the early ’80s. It’s kind of weird that they definitely never showed up until then. Having been there and been around at the time, I would need some very definitive proof.”

Meanwhile, Howard said he does think the posters exist. And Andrew Hawley, a serious collector since 1986, is offering $10,000 for an authentic copy. He told me that based on talking to festivalgoers, he does believe the poster is scarce but real, even if it was printed by an unauthorized creator.

The controversy pits friend against friend, such as with music author Joel Selvin and Amoeba Records co-founder Dave Prinz. On display at the Amoeba shop in San Francisco is what Prinz believes is an authentic, yellowed Altamont poster that he bought from a music industry veteran in 1982 as part of an estate sale. He paid only $10 for it, but became convinced of its authenticity after consulting a local poster expert.

After Selvin told Prinz there was no such poster, Prinz “was so upset he kicked me in the shin,” Selvin said. He added that he even contacted Sam Cutler, the Stones’ tour manager in 1969, to confirm it.

“I love Joel, he’s a good friend of mine,” Prinz said. “It’s almost like having a family member who likes Trump. You just don’t bring it up.

“One day I’m going to sell that poster for $100,000, and then we’ll see who’s right.”

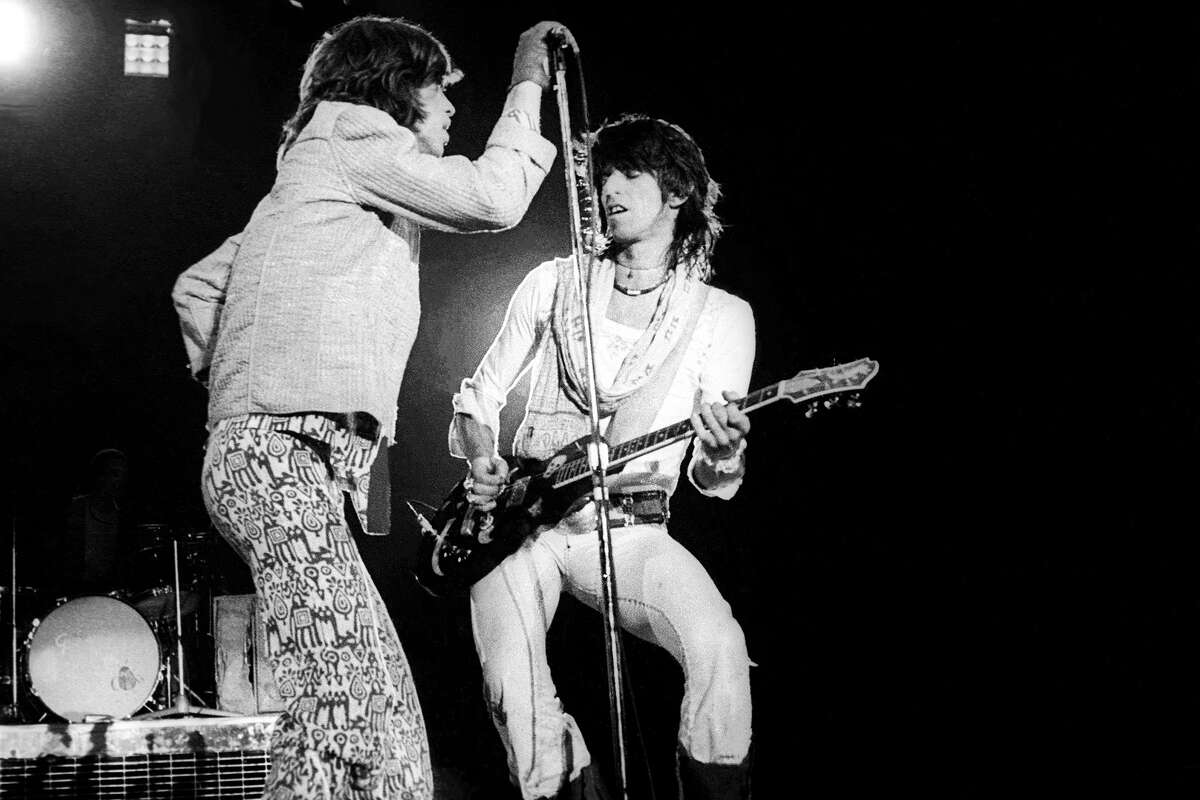

Rolling Stones members Mick Jagger and Keith Richards perform at the Cow Palace on July 15, 1975.

Larry Hulst/Getty ImagesBoth friends defer to the expertise of Jacaeber Kastor, an artist and psychedelic art curator who founded the celebrated Psychedelic Solution gallery in New York. Kastor told me he thinks posters such as Prinz’s are likely merchandising pieces made soon after the concert. As in, not real. But that doesn’t mean Kastor thinks the posters are worthless.

“One guy called me up to ask if he should buy it at an auction,” Kastor said. “I said I don’t think it’s worth the money personally, but if someone else wants to buy it down the road, it seems totally worth it.”

“If a lot of people want it and will pay a lot of money for it, it’s sort of like, who cares?” he added.

Which brings me back to my poster. I threw it out in embarrassment soon after learning the truth about it, and I would never buy another copy now. But if I could go back in time, I would probably keep it. It served as the symbol of a memorable vacation with friends, but also of a myth that transcended fact: Mick Jagger and Michael McDonald sharing stage, soundtracking my birth from just a few miles away.