Having a cabinet member with an exclusive focus on the police has had at least four immediate adverse consequences, argues Lukus Muntingh. He asks if it is time for an evaluation of this role.

South Africa is somewhat unique in having a Minister of Police, even if it has existed under other titles such as "Law and Order" (pre-1994) and "Safety and Security" (1994 to 2009). In our neighbouring countries, the political control of the police resorts typically under a Minister of the Interior or Internal Affairs.

In Angola, the DRC and Mozambique, the police reside under the Ministry of the Interior, and in Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe under the Ministry of Home Affairs. The ministerial portfolio would then cover the internal management of the country and include, for example, population records, elections, local government and also the police and prison services. These then exist as departments under the Minister of the Interior or similar title. Having a cabinet member with the exclusive responsibility of the police, as is the case with South Africa, is therefore unusual, especially since it is not combined with Justice (as was the case in the first Verwoerd cabinet) or with other security and defence functions (e.g., Botswana Ministry of Justice, Defence and Security).

The link with the justice portfolio is also fairly common in other jurisdictions since the police are an integral part of the criminal justice system and integration, if not at least close cooperation, with the prosecution service would be natural.

The first South African minister of police was B.J. Vorster in the second Verwoerd cabinet, albeit as Minister of Justice and Police.

In September 1966, the portfolio was split after less than a year and became the "Minister of Police". Vorster simultaneously held the position of Minister of Police and Prime Minister until 1968, following the assassination of Verwoerd in September 1966. The history and character of the South African Police (SAP) that followed are well-documented, and a few summary points will be sufficient.

SAP under apartheid had a very particular character and purpose. It was para-military in nature and there to keep the minority regime in power. It had largely unfettered powers and little was done to hold it accountable and transparent. State of emergency powers, especially during the latter half of the 1980s, entrenched this colonial and para-military character.

Come 1994, it may have been well-justified to retain the exclusive cabinet portfolio for the police to oversee the integration and transformation of the SAP and homeland police forces. Nothing was assured, and the risk of insurrection from within the security forces was real.

More recent data on police performance is not encouraging, with an increasing number of murders per year, a decline in the number of successful prosecutions, high numbers of human rights violations and other crimes implicating the police as per Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) data, and poor discipline, to name a few.

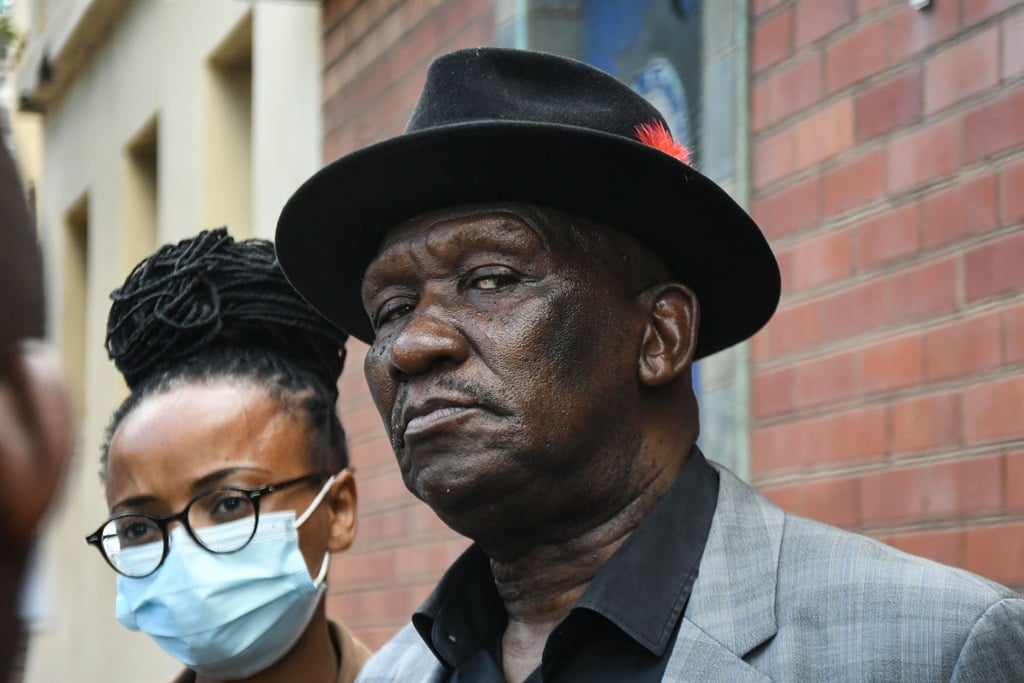

Most important, however, is the extremely low levels of public trust in SAPS and the consequent legitimacy deficit of the police. Given the overall picture of poor police performance, a closer examination of the current structural arrangements is necessary and thus to ask the question: Do we need a Minister of Police? In order to be balanced in the analysis, it is, of course, necessary to take the current incumbent out of the equation, but it would be disingenuous to pretend that his performance had no bearing on the initial prompting of the question.

What, then is the job description of a Minister and, more specifically, that of the minister responsible for the police? The Constitution, in section 85, sets out the executive powers of the President and cabinet members being: implementing national legislation except where the Constitution or an Act of Parliament provides otherwise; developing and implementing national policy; co-ordinating the functions of state departments and administrations; preparing and initiating legislation; and performing any other executive function provided for in the Constitution or in national legislation. The Constitution does not prescribe the required portfolios of cabinet and leave that to the discretion of the President, but it does require that there must be a cabinet member responsible for the police. It is then foreseeable that the portfolio of policing may be combined with one or more other national portfolios as cited in the examples above.

A central function of the cabinet member responsible for policing is that he or she must "determine national policing policy after consulting the provincial governments and taking into account the policing needs and priorities of the provinces as determined by the provincial executives". Moreover, the national policing policy may provide for different policies in respect of the different provinces. This mandate is then derived from the power to develop and implement national policy as set out above with reference to the general powers of the executive.

Policy-development function

The President appoints the National Commissioner of Police to "control and manage the police service". The input of the Minister is not required in the selection. It is then the task of the National Commissioner to exercise control over and manage the police service in accordance with the national policing policy and the directions of the Cabinet member responsible for policing.

It is also the responsibility of the National Commissioner to appoint the Provincial Commissioners with the concurrence of the provincial executive, but in the event of the disagreement the cabinet member responsible for policing will mediate between the National Commissioner and the provincial executive. The provincial commissioners are then responsible for policing in their respective provinces as set out in national legislation, and subject to the power of the National Commissioner to exercise control over and manage the police service.

From the preceding, it follows that the relevant minister has a largely policy-development function and that it is the task of the National Commissioner and those under his or her command to implement the policy and applicable legislation. Moreover, with reference to the minister's policy development mandate, the Constitution makes it clear that there must be consultation with provincial governments and that their identified needs, plans and priorities must be given due consideration in the national policing policy and that a multiplicity of policies is possible.

The Constitution does not set down a time frame for the national policing policy, nor does the SAPS Act, but it can be anticipated that it will be a multi-year focus to tie in with the medium strategic framework and budgetary cycles.

Having a cabinet member with an exclusive focus on the police has had at least four immediate adverse consequences. The first is that it has unduly politicised the portfolio simply because the minister wants to place himself and the police in a favourable light. While this is an inherent and understandable political desire, it also shields the police from criticism, effective oversight and facing some difficult issues, such as the human rights and corruption records of the police.

Crime is a highly politicised issue in South Africa, and having a minister downplaying the crime situation does not foster confidence in the police.

Low levels of public trust in the police are the result of poor police performance and populist rhetoric by the minister will not address the legitimacy deficit.

Part of the blame for the poor performance of the police can at least be laid at the doors of Parliament. Even if this failure is not unique to the police, the fact remains that the police are not being held accountable by the state institution with an explicit mandate to hold the executive accountable.

Poorly paid

It should also be noted that SAPS is a large employer in the national government and although somewhat dated, in 2015/16 nearly half (46%) of national government department employees were employed in SAPS. SAPS members were, however, not particularly well paid compared to their colleagues in national government and ranked 44th out of 47 departments with the Office of the Chief Justice earning on average the best salaries. Addressing remuneration and employing more people may thus be important political priorities for the Minister.

Secondly, the minister’s mandate is clearly one focused on policy development and providing strategic direction. The Public Service Act assigns the task of maintaining efficient management and administration of the departments to the directors-general (the National Commissioner in the case of SAPS).

The ministers are mandated with final accountability and authority on human resources and the organisational establishment of departments. Regardless of where the President would allocate the portfolio of police at ministerial level, these functions will remain as constitutionally mandated duties.

The National Commissioner (and those under him or her) are responsible for implementation and operational management. There should thus be an arm's length relationship between the Minister and the National Commissioner, especially where it concerns operational issues. There has in recent years been allegations that the current Minister is interfering in operational matters.

The Minister's performance agreement with the President provides at least a part explanation for the allegations of operational interference as the agreement is replete with operational targets as opposed to strategic and policy interventions. The performance agreement also notes that, in general terms, policy development is not a problem but implementation is.

It should, however, be noted that the national policing policy, as required by the Constitution, is not in place and an initiative by the Civilian Secretariat for Police has seemingly lost momentum. It then appears that since 1996 no Minister of Police has been able to fulfil an explicit constitutional obligation to develop a national policing policy.

The third adverse consequence is that a Minister of Police intentionally or unintentionally undermine coordination and cooperation in the criminal justice system. As it stands now, with reference to the criminal justice system, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DJCD), the Department of Correctional Services (DCS) and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) are under the Minister of Justice and Correctional Services.

Despite many efforts over the years, coordination in the criminal justice system has remained wanting, primarily because distinct and insulated key performance indicators are used by the respective role players as opposed to key performance indicators measuring criminal justice system results and impact. For example, the police arrest some 1.6 million people annually year, but between 10% and 15% result in convictions and even less in imprisonment. This reflects an enormous waste of time and resources. Similarly, the NPA reports a conviction rate in excess of 90%, but does not relate this to the number of crimes reported, or even investigated. The NPA is also quick to point out that it can only prosecute what the police investigate and place before it.

The NPA can under certain circumstances, investigate and can surely guide police investigations more generally. Much of the police's mandate relates to the investigation of crime, an activity it engages in, in order to place dockets before the NPA as part of its mandate to "prevent, combat and investigate crime".

The strict institutional demarcation between investigations and prosecutions has at least been maintained by the existence of a Minister of Police who would inevitably report on police performance in the most favourable light and that means insulating it from other performance data providing an alternative or more critical reflection. Fourth, it appears that ministers responsible for the police do not stay particularly long in their positions and this instability has not served policing well. The average term in office since 1966 is three years and 10 months. The longest-serving was Charles Nqakula at six years and five months and the shortest Fikile Mbalula at 332 days. Instability in the position of National Commissioner has added to the problem.

All indications are that the criminal justice system is performing poorly and it is worsening, especially since 2010. For example, in 2012, murder was at its lowest since 2006, with 15 554 murders reported and by 2022 this had increased by 62% to 25 204.[22]

It is estimated that 2022/23 will see close to 27 000 reported murders as 13 428 were already reported in the first half of 2022/23.

The increase started halfway through Nathi Mtethwa’s term in 2012 and continued unabated under Nhleko, Mbalula and Cele. Only the Covid-19 lockdown turned on the brakes a bit, only to increase to 25 204 murders in 2021/22.

Politicisation of the police

The politicisation of the police portfolio and poor performance by the police has resulted in declining levels of trust in the police and most South Africans simply do not trust the police. Having a dedicated minister of police seems to have enabled politicisation, but also shielded the police from effective oversight, resulted in ministerial interference in police operational matters, and undermined cooperation in the criminal justice system.

Doing away with an exclusive minister of police may not only enable improved cooperation and coordination in the criminal justice system, but also give police management the space to change the character of policing in South Africa.

The police are in crisis and in need of a critical evaluation as it is simply no longer meeting constitutional requirements.

Acknowledging a crisis, will enable us to consider options that have hitherto not been placed on the table, or considered impossible or unpalatable. Bringing the police under a more inclusive ministry is one such option and forging closer cooperation with the NPA may enable system-wide performance measurement.

- Lukas Muntingh is an Associate Professor and ACJR Project Coordinator at UWC.

Disclaimer: News24 encourages freedom of speech and the expression of diverse views. The views of columnists published on News24 are therefore their own and do not necessarily represent the views of News24.