Time is running out to update ten million prepaid electricity meters in South Africa.

In less than two years, a software limitation in the programming of prepaid electricity meters could reduce the revenue that authorities receive from the sale of electricity to zero, unless they step in to do something about it.

Vendors, including Eskom and municipalities in South Africa, must execute a relatively simple project to avoid the issue, but the only problem is this project will take some time, and many have hardly started.

The risk stems from a date rollover issue in prepaid electricity meters.

As was reported by the Financial Mail in October last year, prepaid electricity meters are due to stop accepting new tokens after 24 November 2024, unless they are updated through a process called Token Identifier (TID) rollover.

Don Taylor, the inventor of the first integrated prepaid electricity meter, who is heading up the TID rollover project, said that when electricity meters were first rolled out, they needed a way to ensure that the tokens that users punched into their meters were unique.

To do this, the meter designers used time.

A series of the numbers in the token that users enter into the meter is attached to the minute that the token was bought at. To prevent the token from becoming too long, a limit was placed on the total number of minutes that can be attached to a token.

That cap on minutes will be hit on 24 November 2024. After which meters will not be able to accept new tokens, and thus no new electricity credit will be able to be loaded on to the system, unless the meter is updated before that time.

There are 10 million prepaid electricity meters in SA and an estimated 70 million worldwide - with 50 million of them estimated to be in Indonesia, says Taylor.

Solution

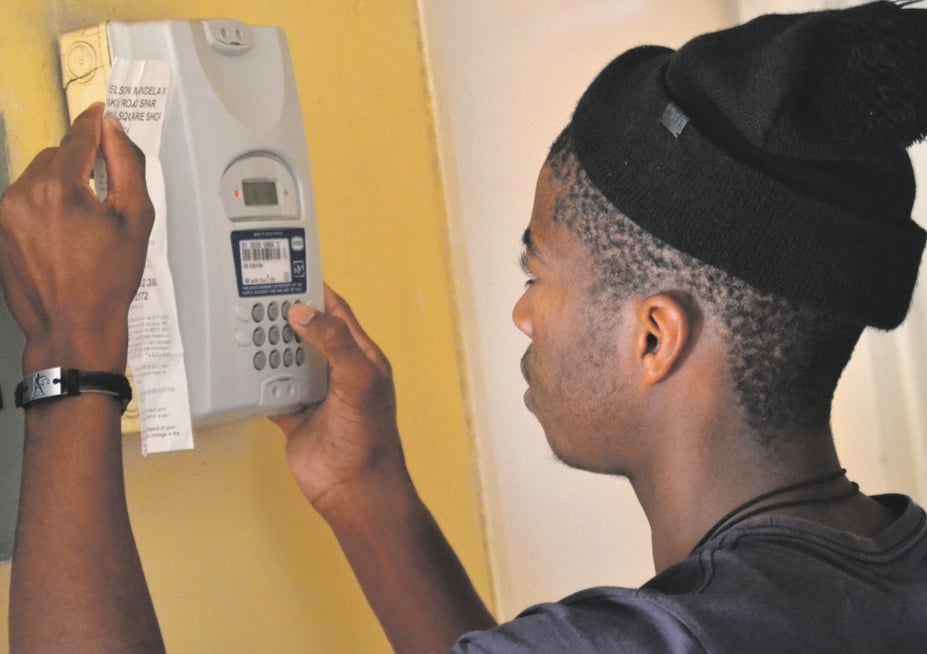

The whole problem is relatively simple to fix. All that needs to happen to update an electricity meter so that it is ready to vend electricity beyond 24 November 2024 is for two unique 20-digit numbers, known as key change tokens (KCTs), to be punched into the meter and then it is ready.

There are two ways this process could play out practically, according to Taylor.

In the one system customers will be given their unique KCTs when they make an electricity purchase and will be expected to enter the numbers into their meter themselves. A municipal helpline could be established to assist meter users in doing this. Eskom said that this is the process they have chosen to adopt to perform the rollover of the meters in their zone.

Alternatively designated task teams could be sent to visit every household in an area to update the meters themselves. This would offer the opportunity to detect meter fraud at the same time, says Taylor.

It is up to authorities to decide which system they want to use, he adds.

Little progress

Riccardo Pucci, a TID rollover project coordinator at the Standard Transfer Specification Association (STSA), said that there is no way that data for the total quantity and rollover status of meters across the world will become available.

“You would love to have a graph that shows every single country, every single state or city, etc, how many meters they have in that location, and then of course, their progress. That information is never going to be accessible,” he said. The STSA can reach out to authorities, but acquiring data rests on the authorities responding with accurate figures, said Pucci.

The STSA is a non-profit association in charge of the technology that allows for the transfer of electricity from a point of sale to an electricity meter, though it isn't responsible for the meter rollover.

The best available data on the progress of the rollover project, which was made accessible to News24, lies in the status of something called Supply Group Codes (SGC).

A supply group code is a six-digit number used to geographically demarcate regions of payment meter installations, according to the STSA website. The number of meters in different SCGs is variable, says Pucci, as some zones may have 10 000 meters in that area, while others have 100 000.

However, the STSA can see whether a rollover project has been started in an SGC.

In SA, 346 out of 1 165 SCG, around 30%, have started, while in the rest of the world 90 out of 790 have, about 11%.

The measure should not be seen to be equated with progress, says Pucci, but it does provide an indication of those who have begun the rollover.

In SA, Eskom told News24 that they have so far rolled out over 5 800 of the approximately 6.5 million meters that they are responsible for in a pilot project in Gauteng.

Local municipalities submit their progress data to a dashboard on the South African Local Government Association (Salga) website. Only 28 municipalities indicated on the site that that they have started their projects.

This lack of progress is in spite of a seven-year communication drive that the STSA has embarked on, says Pucci.

“The sense of urgency out there in the market is basically non-existent. So, what's probably going to happen is you're going to get to the last six months and then everybody is going to wake up, and then you're going to find this frantic rush to try and get things sorted,” says Pucci.

A people problem

The cause of the problem is technical – but only on paper. This is a people problem, says Peter de Jager, who wrote the first article on the Year 2000 (Y2K) computer problem which got widespread media attention and who played a pivotal role in bringing public attention to the issue. De Jager is also an expert in change management and problem solving.

“There are no technical problems. This is not and never will be a technical problem. It's a people problem. It's about people deciding that they need to do this, it's about people deciding that they need to do it early.”

Asked about the meter problem, De Jager says that like Y2K it is a rollover problem, that is where the technical similarity ends.

To save space on computers, when space was a serious issue, programmers often registered the date on computers using two digits rather than four. For instance "1999" was recorded as "99".

The Y2K problem was largely avoided due to a mass program of code reviewal which was undertaken by many institutions. There were still consequences to the rollover problem however.

“In Y2K, we literally did not know where all the dates were. And we had billions of lines of code to look at,” says De Jager.

“This metering problem is very, very, very different. You know exactly what the problem is. I mean, there's no question. It's in every meter.”

Lance Hawkins-Dady, chairman of the STSA board, says: The TID rollover is a mathematical certainty that will impact every single STS prepayment meter."

Despite the certainty of the issue, De Jager says that the inaction from authorities in performing the rollover is not surprising.

“That they haven't done it, Well, that's not surprising. That's the human nature part of this."

According to Hawkins-Dady, other myths commonly believed by authorities, which may offer reasons why authorities have not yet started their projects, include the following:

- Authorities deny that the problem exists, despite the fact that it is a mathematical certainty that the date rollover will occur.

- There is the belief that performing the rollover will not stop fraudulent vending activities and "ghost vending" where electricity tokens are bought from non-legitimate vendors which have illegally obtained the technology required to produce electricity tokens. Updating the meters will stop this activity.

- There is the belief that the existence of safe alternatives to performing the rollover makes the update process redundant. “While some alternatives are being offered in the industry, they are neither safe nor compliant to the specification,” he says.

Foreseeable consequences of failure

Taylor and Pucci say that there will be a dramatic increase in the prevalence of meter fraud if a significant amount of meters are not updated before the rollover date.

“You are going to get record numbers of meter bypasses. That’s essentially what’s going to end up happening. If the revenue protection problem was an issue before, it’s going to skyrocket. And the customers won’t know. They are just going to say, ‘Well, it stopped working. I’m just going to bypass my meter,” said Pucci.

News24 spoke to a qualified electrician who wished to remain anonymous, who said that bypassing a meter is illegal and could be detected by authorities, a qualified electrician could do it in an hour or two.

The electrician said that non-electricians who bypass meters could face fines and possible jail sentences and qualified electricians could face the same punishment, while also losing their licence.

De Jager does not think people will care about the legality of bypassing their meters if they are in a situation where they are without electricity due to an inability to load credit onto their meters.

“Unless this is fixed. Your electricity theft problem will be higher than it's ever been,” he says.

Taylor is not sure what effect communicating this fact to certain municipalities will have on their behaviour.

“You've got to ask the question – what is the reaction going to be from the municipality level? If I judge by the way that they are responding to our notifications in a nonchalant way and a non-understanding way, I ask the question whether they're actually going to care?

“They [municipalities] are bankrupt throughout the country. You can’t get more bankrupt than bankrupt, if you know what I mean. They are going to owe Eskom a lot more money and that is going to have a knock on effect on Eskom,” he says.