Red pandas in Sikkim’s Kyongnosla Alpine Sanctuary face a threat from free-ranging feral dogs that feed on the garbage thrown around Lake Tsogmo. (Photo by Shiv via Wikimedia Commons)

The Markha Valley trek is popular among travellers who visit Ladakh. With a maximum altitude of 17,100 ft, it offers stunning views of the Ladakh and Zanskar ranges. Nearly 6,000 people undertake this high-altitude trek annually. In July 2020, when restrictions were in place due to the pandemic, a clean-up drive was launched along the trek route. A total of 837.39 kg of waste was collected, with camping sites contributing the most amount of waste.

Some locations are disproportionately significant on our planet. They are demarcated as “biodiversity hotspots” - areas with extremely rich and diverse flora and fauna, and deeply threatened. Of the 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world, four are in India: the Himalayas, Western Ghats, Indo-Burma region and the Sundaland (Nicobar Islands). These unique ecosystems attract tourists in large numbers. Ladakh, for instance, is rich in flora and fauna, some of which are endemic to the region. Since 2010, it has witnessed a several-fold increase in the number of tourists, crossing 3,00,000 in 2021.

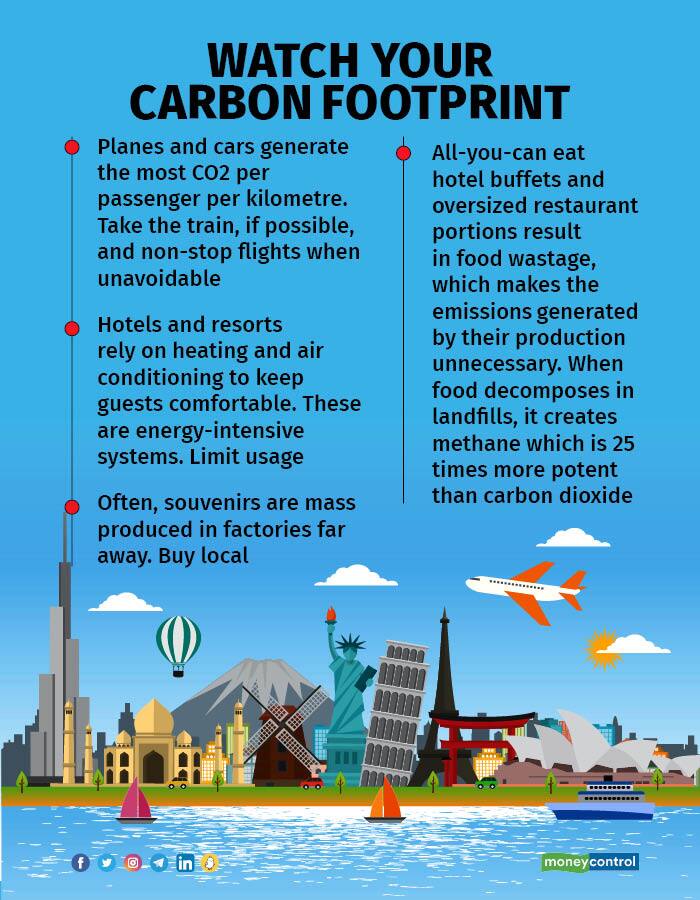

Tourism brings social and economic benefits. What we forget is that it also impacts the local environment by increasing waste generation, deteriorating air and water quality, and boosting land and soil contamination. It puts additional stress on natural resources. For example, Ladakh is a water-deficit area and mostly dependent on snow/glacial melt and the River Indus. Here, the average use of water by a local resident is 75 litres/day, whereas a tourist consumes about 100 litres/day.

It can also severely harm the natural world, leading to loss of greenery and even biodiversity. Red pandas and serows in Sikkim’s Kyongnosla Alpine Sanctuary, for example, today face a threat from free-ranging feral dogs that feed on the garbage thrown around the popular tourist destination of Lake Tsogmo.

Hits and misses

Ecotourism has grown in popularity in recent years in response to growing awareness about the adverse impact of mass tourism on the environment. The International Ecotourism Society defines it as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education”. In 2021, the global ecotourism market was estimated at USD 185.87 billion, and it is expected to reach USD 208.63 billion in 2022.

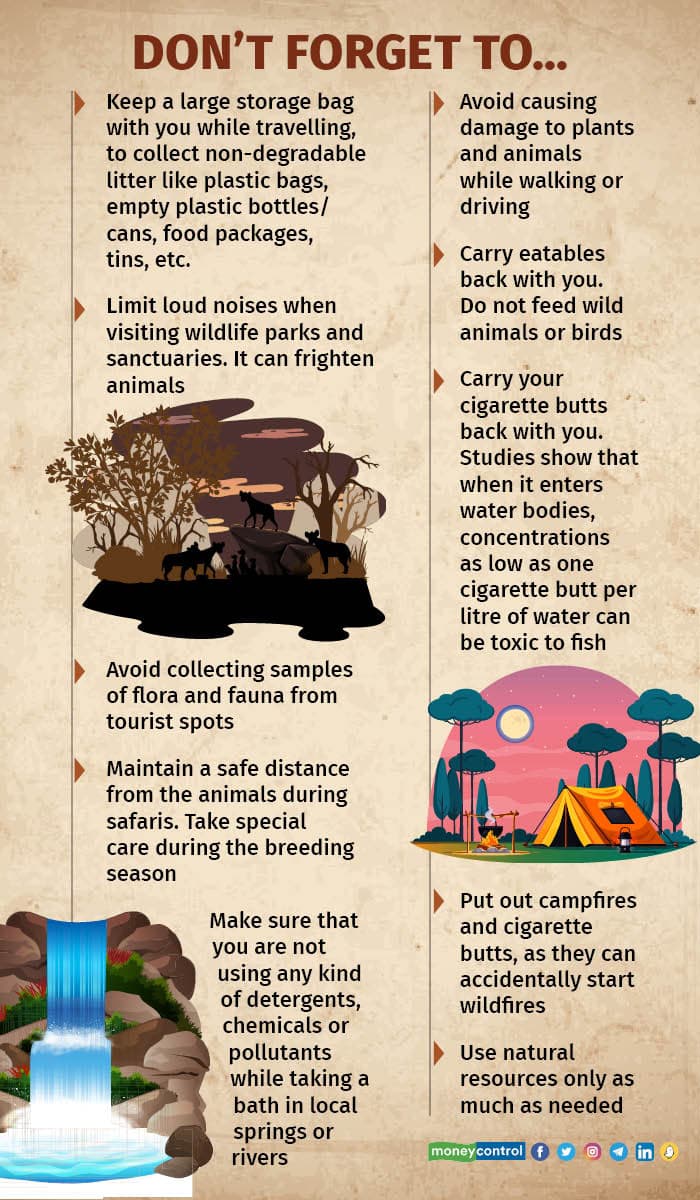

Tourists travel with the best of intentions. Still, it is easy to make mistakes that can actually harm the environment instead of protecting or conserving it.

Take Maharashtra’s Kaas Plateau, for instance. It lies in the Western Ghats and was declared a UNESCO Heritage Site in 2012. To conserve its ecosystem, the number of visitors is restricted, vehicles are prohibited and waste is regularly collected. Still, human presence is proving detrimental.

“The biodiversity here is so fragile that flowers which bloom atop the plateau are not seen a few feet below. Tourists who come to see these flower meadows trample on the vegetation - the biggest threat at the moment. Cars bring pollen. Once these alien plants take root, they threaten the endemic species. As a result, 47-odd flowers are now critically endangered,” says Vijay Karnik, who owns a homestay in the area and conducts walking tours.

Land ecotourism accounted for around 70 percent of ecotourism’s revenue share in 2021. The growth is mainly driven by rising consumer demand for safaris, wildlife watching, and national park visits. But close observation of or interaction with wildlife can be harmful, without checks and balances. Studies show that the presence of humans changes the way animals behave. They may become more vulnerable to poachers, let their guard down around predators, or even grow tamer over time.

Disturbances during sensitive times of their life cycles can have an impact on their population, while feeding by tourists can change social behaviour patterns. For instance, artificial feeding by tourists and motorists passing through Karnala Bird Sanctuary in Maharashtra has resulted in an increase in deaths in animals, particularly monkeys, who risk their lives by crossing roads to eat the food items.

Around 47 flower species are now critically endangered at Maharashtra's Kaas Plateau. (Photo: Parabsachin via Wikimedia Commons)

Around 47 flower species are now critically endangered at Maharashtra's Kaas Plateau. (Photo: Parabsachin via Wikimedia Commons)

Making it count

In a historic moment for the environment, world leaders at this year’s UN Biodiversity Conference COP15 in Montreal reached an agreement to ramp up protections of the planet’s precious natural ecosystems. The deal commits countries to safeguarding 30 percent of land and water considered important for biodiversity by 2030.

These efforts will come to naught unless all stakeholders are equally committed to the cause. When done right, ecotourism can strengthen local communities’ stake in conserving an ecosystem and create a rewarding experience for visitors. Every step counts.

Shashank Birla, whose Wilderlust Expeditions LLP conducts sustainable safari tours in India, says, “Our guests are strongly oriented towards the rules and regulations that are to be followed in the forest to maintain the health of its ecosystem. Non-biodegradable waste is carried back. During safaris, we create awareness on how to limit our carbon footprint in the wild. We also encourage visitors to learn about conservation by volunteering for activities such as clean-ups.”

The time to act is now.