The strength of the movie lies in its being rooted in the regional milieu.

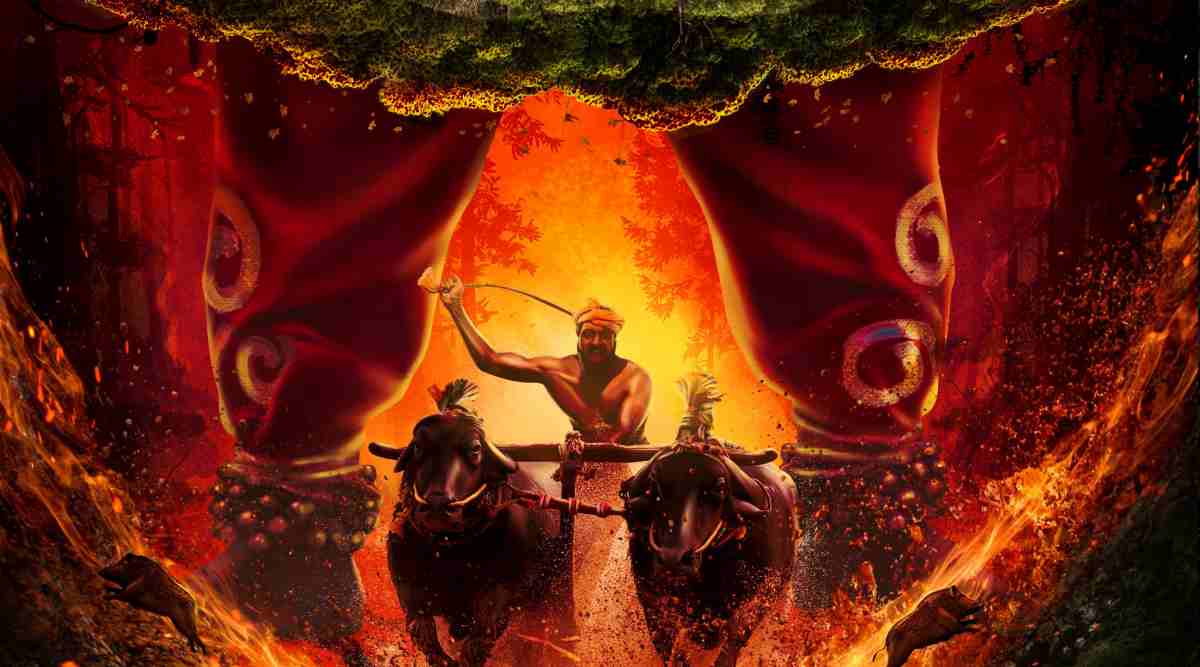

The strength of the movie lies in its being rooted in the regional milieu.There is friction between an oppressor and the oppressed, and the latter takes revenge against the former after several twists and turns. This kind of plot, one of the dominant thematic structures of our films, is enacted against different settings – urban or rural, mythical or historical, among others. Rishab Shetty’s Kantara, the Legend packages this age-old structure in the folk practice, bhootharadhane or bhoothakola, deeply rooted in karavali (coastal) Karnataka – Tulunadu of Dakshina Kannada and the Udupi regions.

In the Tulu cosmos, Bhoothakola is not just a folk ritual practice but the crux of people’s belief system. Bhootha in their imagination is not a negative force but a daiva worthy of worship and offerings. They believe that it is a divine spirit that protects them from calamities and evil forces, and the annual ritual performance associated with worshipping these divine spirits is called Bhoothakola. For example, as picturised in the movie, the ritual of Panjurli (the divine wild boar) is among several types of bhoothakola. Possessing the spirit of daiva, daivanartaka,the dance performer during kola converses with the people addressing their problems and matters of justice.

Bhoothakola is as much an aesthetic practice as a divine belief system. Folk songs, artistic costumes and dances are part of the divine spectacle, and this supernatural world organises the material life of a large part of Tulu life even today. But, as a noted critic from this region Purushottama Bilimale observes elsewhere, so far, no serious attempt is made to document this aspect of Tulu culture nor are there any biographies of performers, agents and actors associated with these practices. Therefore, Kantara, which showcases the cult of Panjurli bhoothakola, assumes importance for reintroducing the locale of karavali life vividly, long after Shivaram Karanth’s (1902-1997) works.

Against the backdrop of this milieu, the plot of the film revolves around the right over land – the rights of the people, the landlord and the state – across three timelines: In 1847, a king in search of peace exchanges his land with forest dwellers for the Panjurli deity, and in 1970, a descendent of the king asks before the bhoothakola that people should give back his ancestral land, but dies vomiting blood as prophesied by daivanartaka.

It is during 1990 that the right over the land becomes a triangular conflict; a later successor of the king’s descendants, now dhani (the landlord) tries to manipulate people to get his land back, and the state’s forest department sees the rights of the people as an encroachment. As soon as we are prepared for the spectacle of the state vs people over the land as an issue of the political economy of modernity, the conflict between dhani and vakkalu (landlord and tenants) overtakes it, and finally, the divine spirit triumphs over the landlord.

First of all, Kantara is not a source of knowledge about bhootharadhane, nor a socially and politically committed cinematic narrative. As someone biased towards high-brow classics and as an Aristotelian in evaluating artistic objects, I call it a flawed cinematic plot. Given the ambition of the film to be an instant box office hit by intently displaying machismo, it might appear too much on my part to demand an artistic achievement from it. But even the climax, which is said to have grabbed the attention of the audience, fails to achieve the cathartic effect. That is, the run-of-the-mill plot prepares the spectator for the denouement – the killing of the landlord — but serves them more with the platter of the bhootha dance than showing the painful fall of the landlord. To offer an alternative to the killing of the landlord, a woman or a voiceless character unexpectedly killing the zamindar would have made a greater impact on the moral suspense of the movie. I have in mind the denouement of plots like Nagraj Manjule’s Sairat (2016).

However, my pedantic criticism should not prevent me from paying attention to its box office collection, especially the Hindi dubbing and an unbelievable mass appreciation of the movie across the country. In this respect, the credit goes to the actor-director Rishab Shetty’s cinematic imagination and coming together of the love, labour and artistic sense of all departments of the movie-making, as usually happens in successful movies. Apart from his scintillating acting, Shetty is at his best in creating subtexts and engaging dialogues. The bawdy and sly innuendos in the movie are nuanced, and the cryptic conversations of the characters leave much room for political criticism and imagination.

The strength of the movie lies in its being rooted in the regional milieu. Rishab Shetty, as revealed in an interview, believes that the more regional the story, the more universal it is. The visual extravaganza of the regional life, which renders the supernatural exotic to cine-goers, has conquered the popular imagination.

These all are internal aspects of movie making. In the public sphere, the movie has become an object of ideological criticism and appropriation. The cinema that treats the problem of land does not make any reference, at least in the subtext, to the land reform acts in Karnataka, introduced by the then Chief Minister, D Devaraj Urs (1915-1982). Even though we can ignore for the moment the politics of representation and appropriation, we should not avoid asking: What will be the movie’s place in our future memory? How often might we revisit this visual text after a year or a decade? Such questions will address not only the art and politics of movie-making but also the culture of film appreciation in India.

The writer is professor, Department of Studies and Research in English, Tumkur University