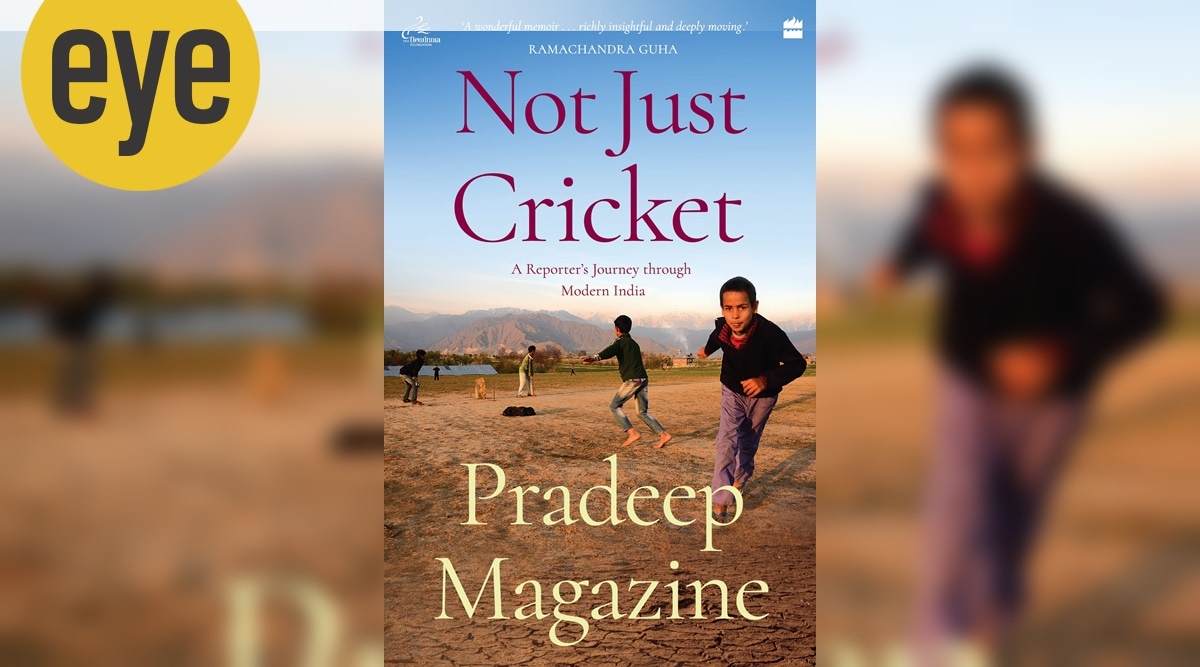

Not Just Cricket: A Reporter's Journey Through Modern India by Pradeep Magazine; HarperCollins; Rs 599 (Source: amazon.in)

Not Just Cricket: A Reporter's Journey Through Modern India by Pradeep Magazine; HarperCollins; Rs 599 (Source: amazon.in)While growing up in small-town Mirzapur, sandwiched between Allahabad and Varanasi, I wanted to become a test cricketer. I had a book on the game by Geoffrey Boycott. As a child, I used to spend hours practising and the high point of my cricketing ability was praise by former test cricketer Mushtaq Ali, when I scored 34 runs against a very good bowling unit of Hindalco, whom he used to coach. But like all youngsters from lower middle-class families, my dream was shattered due to the pressures of education. But the passion for cricket remained. So, when I saw the book by Pradeep Magazine, I just had to read it.

To my surprise, Not Just Cricket is a book not only about cricket. It’s about changing India, with all its ups and downs. It busts myths and reveals the dark underbelly of not only cricket but also society. This is probably the only book of sports which starts and ends with turbulent Kashmir, not in cricketing terms, but with history, personal anecdotes, nostalgia and an oscillation between past and present and an imagination of the future. This is the narration of an author who is subconsciously haunted by memories of conflict; this is the reportage of an Indian who was born in Kashmir, whose community was thrown out of its home; who is desperate to keep his observation objective despite being burdened by the ghosts of time.

Magazine begins his narrative with a description of his family home in Srinagar’s Karan Nagar, where the author had lived till he was eight years old. That child has become an adult but inwardly he refuses to accept the sour reality of the lost world.

I have read Magazine for more than two decades but have personally known him only for a few years. But it was only through the book that I discovered that he was a Kashmiri Pandit, with deep roots in the Valley. In the book, he admits that he is not a sociologist, but he does try to find an answer to why Kashmiri Pandits were driven out. He recalls Nund Rishi and Lal Ded, Sufi saints of Kashmir, revered by Hindus and Muslims both, to trace the reasons behind the conflict between the two. Ironically, he ends up recalling an old Hindu lady, Rattan Rani, who refused to leave Srinagar: “She had the courage not to flee and abandon her roots. I felt, somehow, we had betrayed her.” Is he blaming his own people for leaving the Valley? Only Magazine knows the answer.

The beauty of the book lies in its smooth transition, from society to cricket. While reading contemporary history, the reader moves into the world of Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly, Rahul Dravid, Tiger Pataudi, John Wright and Greg Chappell.

This style of writing requires talent and the connection between both the worlds is magnificent. That makes the book interesting even for those who are not cricket buffs. In the opening chapter, the Kashmir narrative is offset by introductions to Clive Lloyd, the captain of the much feared West Indies team; Tiger Pataudi, the one-eyed charismatic captain of the Indian team, who cemented his place in our cricketing history by “shaping, forging and moulding a diverse group of players with disparate regional loyalties into a unified team.”

Before the surreal world of so-called love jihad became contemporary reality, Magazine writes about the emotional reaction of Sharmila Tagore’s husband and Kareena Kapoor’s father-in-law to the demolition of Babri Mosque. He writes, “For a man who never betrayed emotions, presenting a stoic face and always appearing very distant, it was unnerving to watch him fight tears while narrating what it had meant to be a Muslim during that sordid period of India’s contemporary history.” Tiger Pataudi was not the only one who betrayed his inner turmoil. Cricketers who appear to be supermen in the eyes of their fans are mere mortals too. Pradeep reveals the vulnerable sides of demigods such as Tendulkar and Kapil Dev, who when confronted with adversity, almost broke down.

Indian cricket has not always graced itself with glory. If it has produced magic moments, it has also discredited itself with match fixing and sordid tales of internal politics. Magazine, who was among those who broke the match-fixing story, not only exposes the dark side of Indian cricket but also has the courage to present the other side of the Ajay Sharma story. A colossus in domestic cricket who never got his due internationally, Sharma was one of the accused in the case.

There are times the reader gets the sense that the author knows a lot more but has shared little. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating read. I can relate to him and the book more because, like me, he also wanted to be a successful cricketer, but could not. The book can also be called autobiographical — the author’s inner journey and transformation, the search for his own identity open a window for readers to look within. It makes the book not merely about cricket but about life, too.

(The writer is co-founder and editor of SatyaHindi and author of Hindu Rashtra)