Bonnet macaque (Photo: Richard Saunders via Unsplash)

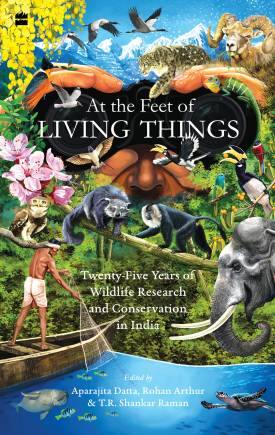

If you are a nature lover who enjoys reading first-person narratives by people who work in the field of wildlife research and conservation, At the Feet of Living Things: Twenty-Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in India (HarperCollins India, 2022) is a must-read. This book is edited by three scientists — Aparajita Datta, Rohan Arthur, and TR Shankar Raman  — who work with the Mysuru-based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF). Young wildlife biologists set up this organisation in 1996 with the vision of “a world where nature and society can flourish together”. Their mission is to “explore, understand and conserve the natural world through research and responsible engagement with society”.

— who work with the Mysuru-based Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF). Young wildlife biologists set up this organisation in 1996 with the vision of “a world where nature and society can flourish together”. Their mission is to “explore, understand and conserve the natural world through research and responsible engagement with society”.

There are five parts to this book: "People and Parks", "Among Wild Species", "Living with Wildlife", "The Fall and Revival of Nature", and "Bringing People and Nature Together". Together, they hold a total of 16 essays based on two-and-a-half decades of work done by the NCF in various parts of India, including Lakshadweep, Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Himachal Pradesh. They document the exhilaration, and challenge of conducting field research in terrains such as forests, coral reefs and mountains.

Apart from essays written by the editors, the volume features essays by Rucha Karkarey, Mayuresh Gangal, Charudutt Mishra, Elrika D’souza, Anindya ‘Rana’ Sinha, M Ananda Kumar, Ganesh Raghunathan, Vinod Krishnan, Sreedhar Vijayakrishnan, Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi, Ajay Bijoor, Teresa Alcoverro, Yash Veer Bhatnagar, Divya Mudappa, Suhel Quader, Pranav Trivedi, Swati Sidhu, Geetha Ramaswami, and P Jeganathan. They have studied primates, dugongs, fish, hornbills, elephants, snow leopards, and other creatures. It is a fine selection of voices addressing the personal and professional, objective and emotional.

In addition to gushing about the breathtaking beauty of remote locations and rare sightings of animals, they also write about why they love their work and how they got involved in the first place, their unpleasant encounters with leeches, getting acclimatised to high altitude, feeling embarrassed by their prejudices about forest-dwelling communities, recruiting field assistants, mediating between tribal elders and the forest department, foraging for food in the jungle with the help of locals who have “extensive practical knowledge”, running malaria-prevention programmes, and setting up kindergarten schools and rural energy initiatives.

The editors argue against a one-size-fits-all solution to deal with the complexity and diversity of contexts where “people and wildlife live cheek-by-jowl, sharing spaces and resources, shaping each other’s environment, plagued by the same forces of changes, each striving to eke out its existence in a crowded country”. The book’s strength lies in its ability to present both sides of the debate — those who advocate for justice, inclusion, and community governance; and those who prioritise law enforcement, policing, and the setting up of protected areas.

In the essay titled The Day of the Macaque, the example of bonnet macaques in Bandipur is used to point out how increasing tourism in sanctuaries is affecting wildlife. Tourists throw nutritionally-rich food at these animals from their cars; this triggers competition between macaques who “appear to naturally gravitate towards humans and their food sources”. They display aggression towards other members of their own species. During the summer, they move close to highways and wait for tourists. What makes matters worse is that the food provided by tourists “is also rather unpredictable and clumped in distribution”.

In another essay, titled Conservation is an Elephantine Journey, we learn how crop damage by elephants is a big issue for farmers but also get to understand that elephants and human beings perceive the same landscape differently. The legal boundaries humans draw between a wildlife reserve and a plantation do not make sense to elephants who “need to traverse large areas and swamps” as “plantations and forest fragments are key habitats for them”. Such reflections in the book help to unsettle the simplistic distinction between victim and perpetrator made by commentators who do not examine how different parties are affected.At the Feet of Living Things invites us to reflect on the urban tendency to romanticise the rural, and to expect an idyllic environment that does not exist in reality. The book acknowledges how conservationists coming from the outside are often ill-equipped to navigate the web of relationships and the structure of hierarchies in local communities. At the same time, it also evokes a feeling of interconnectedness between humans and other life forms. It encourages us to pause and marvel at the non-human, to encourage children to participate in nature-education camps, and to volunteer their own time for citizen science projects that need help with surveys and data collection to understand animal migration.

The book is enriched with black-and-white illustrations by artist Sartaj Ghuman, who is also a wildlife biologist and mountaineer. The cover illustration is by Mohit Suneja, and the cover design is by Saurav Das. These images provide a break from the text and help us imagine ourselves in the wilderness, trying to unravel the mystery of our place in the universe.