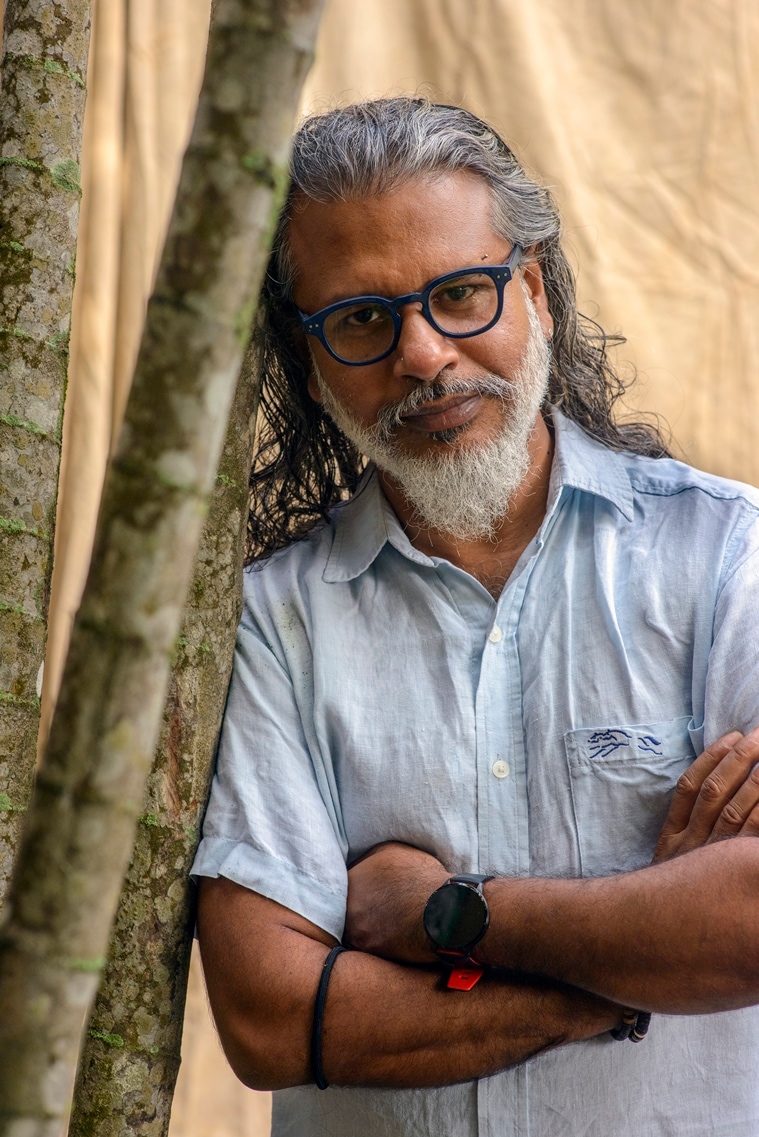

Shehan Karunatilaka. (Credit: Penguin Random House India)

Shehan Karunatilaka. (Credit: Penguin Random House India)Even though the time he gets to spend with his guitar is now decidedly less, Sri Lankan writer Shehan Karunatilaka, 47, has lost none of his rockstar grunge. The black nail paint on his fingers — “male polish”, he calls it — was a hat tip to his “juvenile rockstar ambitions”. “My wife took me for a manicure before the award ceremony. She said you are going to the Booker, you need to look nice. Big mistake! I was getting the manicure and I see all these bottles and I told the manicurist, ‘Can you put something black?’ and here we are!” he says, with a laugh. His phone hasn’t stopped buzzing since the time he became the second writer from Sri Lanka to win the Booker Prize for his novel The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida earlier this week. “We won the Asia Cup (cricket tournament) but we haven’t had many victories in Sri Lanka in the last year,” he says. In this interview, the Colombo-based writer speaks of his literary influences and why the novel went through a rigorous round of re-editing. Edited excerpts:

You mentioned in your acceptance speech that you could not set the novel anywhere but in 1989. Why is that so?

Shehan Karunatilaka. (Credit: Penguin Random House India)

Shehan Karunatilaka. (Credit: Penguin Random House India) My initial idea or conceit was to make it a ghost story. If the silenced voices of Sri Lanka’s conflicts were allowed to speak and speak freely, what stories would they tell? When I was writing in 2010-2011, right after Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew (2010, his debut novel), what was freshest in mind was 2009, the end of the war that we thought would go on forever. We knew they were huge civilian casualties, the numbers kept getting pushed around. There was no truth or reconciliation, not enough. That central thing they were arguing about was whose fault it was. And so, I thought a ghost story would be a neat way of exploring this. But I wasn’t comfortable because it was contemporary history, and, in South Asia, you are always wary about offending the wrong people. So, I went back. I could have gone to ’83 (when the war began), that would have been obvious, but that story has been well-documented and I felt that it wasn’t my story to tell. I was a Sinhala Buddhist male. I was the oppressor, I wasn’t the one who suffered great loss during that period. But, as a teenager, I remembered ’89. I wasn’t aware of much of the politics but I remember how uniquely messed up it was for Sri Lanka. We had the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam), the JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party in Sri Lanka), the Indian Peace Keeping Force on the ground. Within the framework of a typical murder mystery, I got to explore this period that I wasn’t that aware of at 14-15 (years of age). It’s only later that I read about it and found out that it was more absurd than I ever thought it was.

You spoke of your debt to Kurt Vonnegut, George Saunders, and Douglas Adams. Sri Lanka itself has a robust literary legacy. Did that influence you anyhow?

Growing up, there wasn’t a Sri Lankan section in the bookshop. We might have had a few Sri Lankan books written by some professors. But in the ’90s, that all changed and Michael Ondaatje deserves a lot of credit for that. He wrote Running in the Family (1982), which was a seminal book. Suddenly a book was talking about my street and my neighbourhood. Then Romesh Gunesekera was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Reef (1995). But these are two expat Sri Lankan writers writing very elegant, crafted, beautiful prose, which, as a young writer you aspire to, but can never write like. Then there was Shyam Selvadurai, who published Funny Boy (1994), a quite groundbreaking gay coming-of-age story. But for me, Carl Muller was the guru. He was the first writer unlike the rest that I described, who wrote like Sri Lankans spoke, he told stories like us, and I borrowed very heavily for Chinaman the idea of a drunken uncle telling a story and the style that they would tell it in. It was quite liberating. We could write in our own voice and tell stories of ourselves, not like an outsider looking in and doing a forensic analysis on it.

Also, with Ondaatje winning the Booker, he donated his prize money to set up the Gratiaen Prize (Started in 1992, the annual prize recognises a work of outstanding literary merit in English by a Sri Lankan resident). It’s genre agnostic, and that was the goal for us. I wanted to write something that I could enter in the Gratiaen Prize (Chinaman won in 2008). That’s why there has been a lot of Sri Lankan writing in English. But, apart from the writers of the ’90s, certainly Kurt Vonnegut, George Saunders and Douglas Adams — you can see the commonality, they’re writing about quite serious topics, but they have that freewheeling tone, and it’s almost like a trick. They get you interested, and then you suddenly realise you have read a very grim subject.

The book came out as Chats with the Dead (Penguin India) originally in 2020. We ran an early excerpt from it as a short story in our Sunday magazine. How different is The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida from the 2020 version?

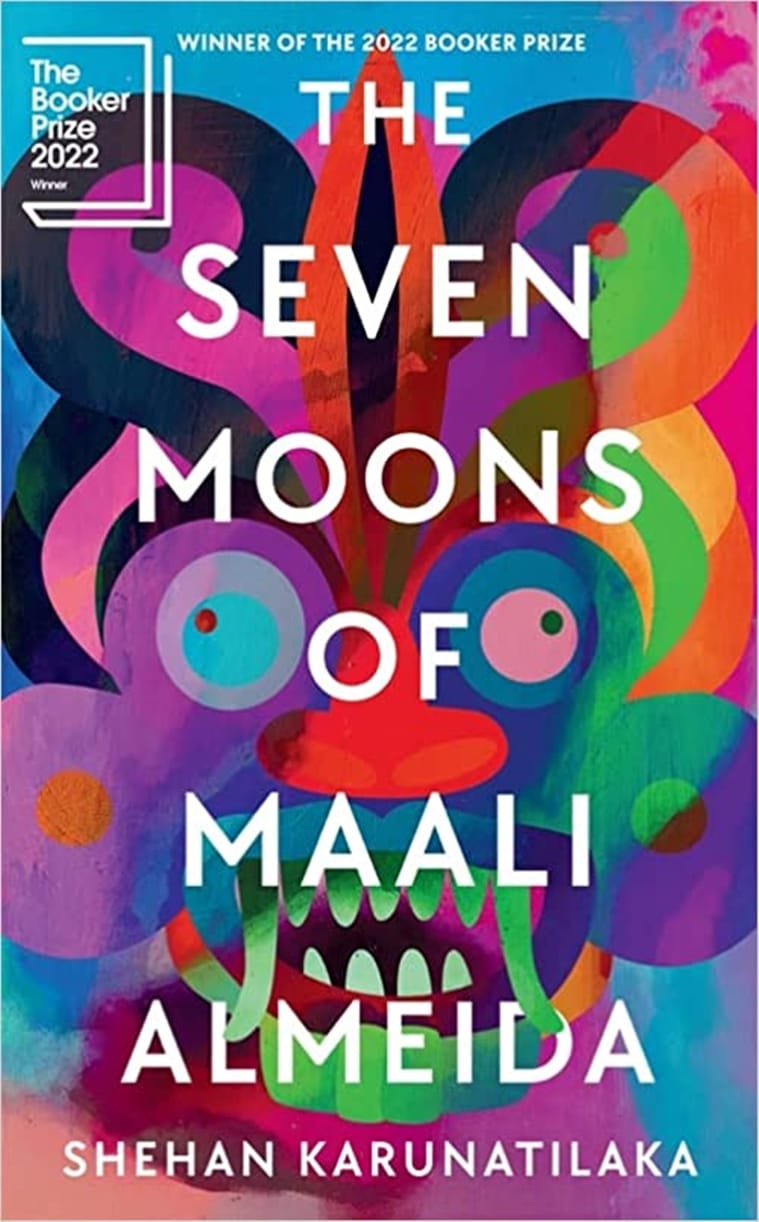

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka; Sort of Books; 368 pages; Rs 1745. (Source: Amazon.in)

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka; Sort of Books; 368 pages; Rs 1745. (Source: Amazon.in) When the manuscript of Chats with the Dead reached the Indian publishers, many were enthusiastic. Chinaman had a loyal set of fans, it was fondly regarded even 10 years later. So, there was an appetite for the second book. But that wasn’t translated anywhere else. I felt I wasn’t sure. Does it need more work? Is it clear enough? The Indian subcontinent knows of Sri Lanka, the LTTE, the war. But, maybe, it confused the UK publishing industry. Many said it just seems chaotic and very hard for UK readers. So, when I finally found (independent UK-based publishing house) Sort of Books and Natania Jansz (co-founder, along with husband Mark Ellingham) took it on, she said, ‘I think it’s a terrific work, it could be a very big book, but we need to do some proper work on it.’ Initially, we thought, let’s just clarify and make the Sri Lankan situation clear. But when the pandemic happened, we couldn’t publish in 2020. So we had nine months. Then you start looking and saying, Well, is this subplot working? Is this bit boring? Does this character work? There was a lot of taking out bits that didn’t work and rewriting new scenes. But essentially, it’s the same book in that it starts with the same premise and ends in the same place and same character.

Do incidents such as the attack on Salman Rushdie earlier this year make writing about politics difficult?

I’ve always been cautious. In my first book, I thought, can you write a Sri Lankan story not mentioning the war — that was my challenge to myself, because all the stories we got, the war was always part of it — and I thought cricket and arrack, and I felt safe.

This was obviously more overtly political. But again, I didn’t feel threatened because I was writing about ancient history. It’s 30 years ago. The Easter attacks feel long ago, even though it was three years ago. Now, we’ve got our 2022. But with my short stories, Birth Lottery and Other Surprises (Hachette India), that has just come out, those were a lot of stories collected over 20 years. During the pandemic, I picked the best and I asked that question and I did self-censor. I did exclude a few because I thought maybe this might offend certain political or religious interests. Look, I’m not a hero. I’m not an activist. I know we speak of freedom of speech as a right. But we have had periods in our history where it’s been very dangerous to speak out. I’ve got young kids, I’d like to live a long and healthy life, and it’s only a short story.

What next?

I have started a third novel. I can’t talk about it, it’s bad luck, but I will say it’s got to do with Sri Lanka in the 2000s. This one was a heavy book to write, the next one will be much lighter. It will have to do with Sri Lankan absurdity, that’s as much as I can tell.