How George Floyd protests inspired domestic terrorists in Michigan: 'This might be it, boys'

Tresa Baldas

Tresa BaldasAs civil unrest roiled America in the wake of George Floyd's murder, a group of militiamen in Michigan were secretly organizing a revolution of their own that spring of 2020, and gleefully rejoiced at the mayhem that was convulsing cities nationwide.

"I’m glad they burned the precinct down. The boogaloo is happening," one man posted in a group chat on May 29, 2020, referring to the torching of the Minneapolis police station the night before and using their term for civil war.

"Why can’t this (expletive) happen in Michigan so we can start the boog?" another man asked, noting he wasn't interested in the "whole cop murdering Black people thing" — just the anti-police sentiment.

For the militiamen, the Black Lives Matter movement was a sign their boogaloo was near.

"I really think this might be it, boys," one man stated. "The whole country is going wild ... I'm so happy."

'Time to strike'

In what is now the third trial in the plot to kidnap Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, state prosecutors Tuesday unveiled secret chat room discussions that they allege highlight the unfolding of a domestic terror plot, where men with hate for cops and politicians seized a pivotal moment in U.S. history to launch their own revolution.

While the trial is about three men allegedly helping terrorists commit bigger crimes — plotting to kidnap the governor and kill police and politicians — the state case focuses more narrowly on the growth of violent extremism in America, and how the Black Lives Matter movement may have energized domestic terrorists.

As one of the defendants told his cohorts the day after the Minneapolis police precinct was torched: "Now’s the time to strike. Iron is hot."

Vetting process: Are you willing to be labeled a terrorist?

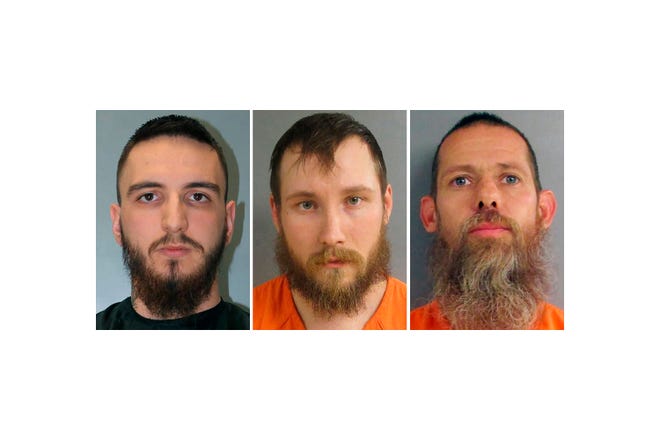

The defendants are Paul Bellar, Joe Morrison and Pete Musico, who are charged with providing material support for a terrorist act — a plot to kidnap the governor — and face up to 20 years in prison if convicted. Four others were convicted of kidnapping conspiracy in a separate, federal case; two were acquitted at trial.

As in the federal case, the defendants in the state terrorism trial argue they were not part of any domestic terror plot, but were merely disgruntled citizens who were engaged in tough talk during turbulent times: the pandemic, the lockdowns, the masks.

More:How a Milford landlord helped feds bust alleged Whitmer kidnap plot

More:Jury convicts Adam Fox, Barry Croft Jr. in Whitmer kidnapping plot

But the FBI argues that they did a lot more than talk. They were part of a paramilitary group called the Wolverine Watchmen that held breaking-and-entering drills, built kill-houses, held bomb-making experiments, had rules to join and a poignant vetting question: Are you willing to be labeled a terrorist?

In court Tuesday, jurors heard a recording of Morrison ask just that question, saying: "Would you be willing to be called a domestic terrorist in the near future?"

FBI Special Agent Henrik Impola testified that he heard Morrison ask that question 12 times.

A road trip to Detroit

It didn't take long for the BLM movement to reach Detroit, where demonstrators protesting police brutality and demanding reforms took to the streets for weeks after Floyd died in May 2020 under the knee of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who was later convicted of murder.

The Wolverine Watchmen were excited about the protests.

"They gonna drag these cops in Detroit, lol," Morrison said in one chat, describing his excitement as like being sexually aroused.

Musico asked: "What’s the plan if Detroit breaks out in a larger riot?"

"Boog," Morrison responded.

On May 28, 2020, the group headed to downtown Detroit in a truck for what they called a QRF: a military term for a quick response force to a developing situation. The group had learned that rioting was starting to take place in Detroit, and they prepared for action. One group of Boogaloo Bois would be with the marchers monitoring police, while the Wolverine Watchmen would be on standby, ready to help extract the Boogaloo members should they get arrested.

More:How 2 militia members turned on their comrades in Gov. Whitmer kidnap trial

More:Juror's daughter-in-law got high with kidnap defendant Fox near Whitmer cottage

Before heading to Detroit, the group first met at Bellar's home in Milford, held a briefing with a whiteboard, sketched out roles, pulled up Google maps and used a flight tracking app to figure out which law enforcement flights were in the air to avoid possible detection by a police chopper. Defendant Ty Garbin, who pleaded guilty in the federal case, was an airline mechanic and had access to the app.

The FBI, however, had undercover operatives inside the group who called the Detroit FBI office and alerted agents about the crew's road trip.

Big Dan takes the wheel

An undercover informant referred to as Big Dan drove the crew because the FBI feared what may happen if the group was pulled over by police. As agent Impola testified, Musico had previously talked about trying to get the names of police officers, tracking them down at home and killing them. And the others were also anti-police.

So to prevent a potential shootout with police, the FBI put Big Dan at the wheel, presuming he would calmly handle any police interaction. Plus, the Detroit police and FBI were alerted that the militia group was headed to town from Milford.

"We didn't want anybody to get hurt," Impola testifed.

According to trial testimony, while driving to Detroit, one of the defendants said if the group were to get stopped by police, they would shoot — though that never happened. Instead, the group drove to a dark parking lot near the Masonic temple in midtown and waited there while the BLM march went on just blocks away.

Morrison was not there, nor was Musico — though Morrison checked in and asked for a report about what was happening.

Bellar responded that a march was happening, "a BLM march, a riot, a protest, whatever the (expletive) it's called." No Boogaloo Bois were arrested.

Morrison messaged the group after midnight: "Good night kings. Good work tonight. I’m proud of each and every one of you. Wish I could have been with you."

Flint road trip

One day after visiting Detroit, another so-called QRF crew was deployed, this time to Flint.

The Wolverine Watchmen had learned that there may be civil unrest related to a BLM march there. So Bellar and others headed to Flint, where they went to an old farmer's market about a mile away from the planned BLM protest and waited. Bellar brought along his loaded gun, though one of the defense lawyers protested to the jury on Tuesday: "They're legally armed at a protest. They've broken no law."

The group had no contact with police in Flint, either. The march was relatively quiet and peaceful. Bellar and others returned home.

However, the FBI maintains, the plan to harm police and politicians never ceased. Rather, the government argues, the defendants and others continued to meet, trained others on how to conduct breaking-and-entering missions, held bomb-making experiments and shooting exercises, and talked incessantly about their hate and mistrust of the government.

On Tuesday, Impola testified about tactics practiced during training exercises as jurors heard recordings of the defendants giving others instructions on how to “stagger” in a hallway to clear it, and not to “buddy up” so that something doesn't "blast through the (expletive) doorway." They were training to kidnap the governor, the prosecution maintains, alleging the Wolverine Watchmen spent months organizing and training, and operated like a gang.

The use of the word "gangs" has long incensed the defense.

"We keep hearing gang, gang, gang," Morrison's attorney, Leonard Ballard has previously argued, maintaining the defendants weren't gang members, but merely "a collection of guys who were tired and frustrated" with their government.

Bellar's attorney, Andrew Kirkpatrick, also has scoffed at the terrorism claims, saying his client ultimately left the Wolverine Watchmen because he thought the ringleader was crazy. "Did he materially support terrorism? ... Give me a break."

But the prosecution in the state case, as in the federal case, argues this case is about violent extremism. The Wolverine Watchmen were domestic terrorists, they say, and they were determined to hurt the governor and police as part of a bigger movement to spark a civil war.

"These guys were serious, ladies and gentlemen," Michigan Assistant Attorney General William Rollstin argued to the jury as he compared the defendants to the mujahedeen, fanatical Muslims intent on holy war. To bolster his point, he said they even called themselves the "boojahedeen."

Trial resumes Wednesday at 9 a.m. in Jackson County Circuit Court.

Tresa Baldas: tbaldas@freepress.com