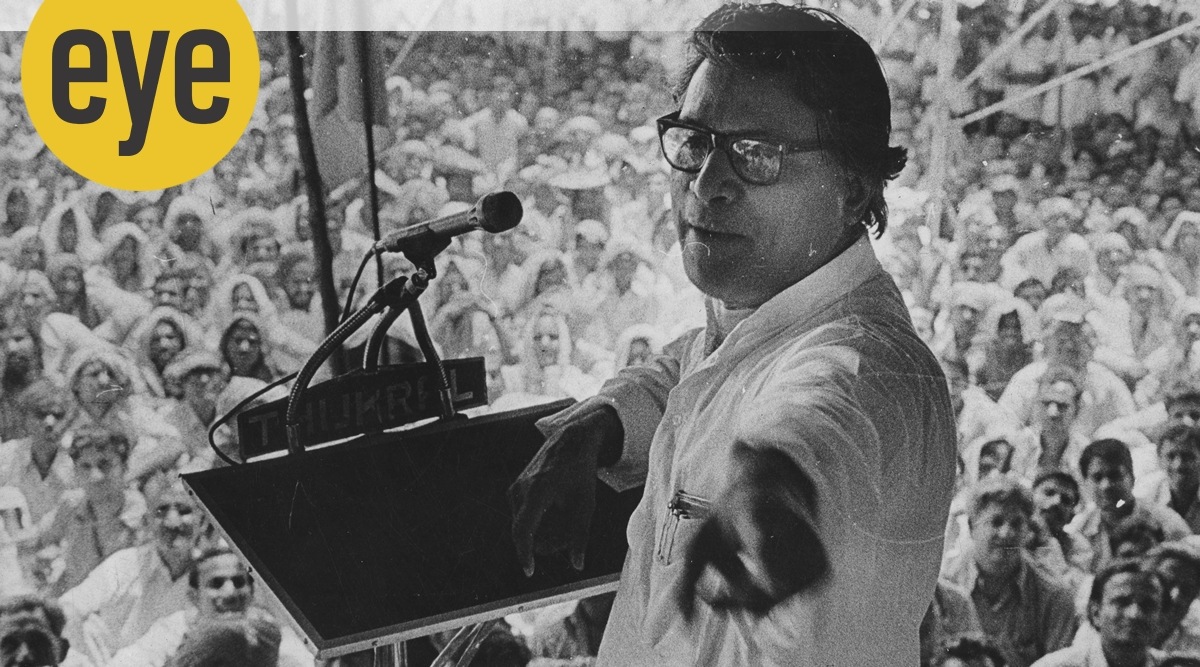

George Fernandes addressing an All India Railwaymen’s rally in Delhi on May 8, 1979. (Credit: Express Archive)

George Fernandes addressing an All India Railwaymen’s rally in Delhi on May 8, 1979. (Credit: Express Archive)Socialism is cursed. Perhaps, no political ideology in the world has gone through as many virulent mutations as socialism has. Its irresistible charm had once appeared likely to embrace the entire world. The language and idioms emanating from the practitioners of socialism turned out to be fatally seductive to people of many nations, yet these continued to get traction.

The Indian variant of socialism tried to chart a different path right from the beginning. It broke free from classical Marxist socialism and claimed to be a political philosophy rooted in Indian reality. With the exception of Acharya Narendra Deo, each of the stalwart socialist leaders such as Ram Manohar Lohia, Madhu Limaye and George Fernandes, belonged to an exceptional genre — articulate and intellectual with highly inconsistent public conduct.

The Life and Times of George Fernandes is a comprehensive chronicling of the maverick leader whose inconsistencies are the stuff of legend. Recall the George Fernandes of the ’70s, and you remember a fearless, handcuffed young man with a defiant demeanour. Those were the times when Che Guevara was still the youth icon, and student unrest across the world in the late ’60s was not yet in the distant past. Fernandes emerged as a powerful trade union leader in the shadow of a student movement that snowballed into a popular protest against the mighty prime minister Indira Gandhi. He was not a student leader, but he captured the spirit of the time by taking recourse to militant methods of protest. During the Emergency, he was accused of planning to execute explosions across the country to paralyse the government.

The Life and Times of George Fernandes: Many Peaks of a Political Life by Rahul Ramagundam; Penguin Random House India; 624 pages; Rs 799. (Source: Amazon.in)

The Life and Times of George Fernandes: Many Peaks of a Political Life by Rahul Ramagundam; Penguin Random House India; 624 pages; Rs 799. (Source: Amazon.in) Once again, the tactics and strategy he seemed wedded to were quite akin to guerrilla warfare, usually preferred by subversive ideologies on either extreme — right or left. Herein lies the catch. Which ideology did Fernandes espouse? The book that traces the curious trajectory of Fernandes’s life is unable to find the answer. In reality, there is none. Fernandes’s socialism was anarchic, self-serving and agnostic to the left-right binary of ideologies. Call it opportunism if you like, but Fernandes remained unflappable. When Morarji Desai was forced to quit as prime minister, to be replaced by his rival, Chaudhary Charan Singh, in 1979, Fernandes demonstrated his oratorical skills by arguing for both sides with equal vehemence.

But why should anybody blame Fernandes for this inconsistency? Before him, his mentor, Ram Manohar Lohia — one of the most revolutionary thinkers of his time — had also displayed similar inconsistencies. From being a Gandhi acolyte close to Jawaharlal Nehru, Lohia not only turned against the Congress but found a common cause with the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the precursor of the BJP. He disdained Indian Marxists. But Lohia revolutionised Indian politics by introducing the grammar of castes into it. His battle cry for extending reservation benefits to the OBCs resonated across the country and spawned a political programme that subverted traditional politics. As a result, from the late ’60s, the Congress, for the first time, began ceding political ground to the regional forces across the country. Thus began the era of an axis of non-Congressism. Fernandes was the product of that era.

But look at the irony that Fernandes was literally a fanboy of Jawaharlal Nehru. He was so fond of him that he joined the socialist movement with a precondition that Nehru would not be replaced, should the socialist movement succeed! But in the post-Nehru phase, he developed a pathological aversion to Nehru’s successors, from Indira Gandhi to Rajiv Gandhi and Sonia Gandhi. At times, he would not mind getting personal with the family. The cause of this could be traced back to the sufferings he and his family had undergone during the Emergency, apparently at the behest of Indira Gandhi. Fernandes remained bitter about it till the end.]

Ramagundam’s detailed research gives a graphic account of this unusual leader’s political prowess, chicanery and betrayal, as well as his messy personal life on account of his estranged wife and liaisons with other women.

The biography brings alive the personal life of the maverick who betrayed many in his quest for power and eventually got betrayed in return. Towards the end of his eventful life, Fernandes was reduced to a caricature of his former self by his own comrades-in-arms such as Sharad Yadav and Nitish Kumar. As his party Janata Dal (U) was confined to Bihar, his stature on the national stage was substantially diminished. By the end of 2004, he lost control over the party and was replaced by Sharad Yadav as the party president. In the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, his party even denied him the ticket. He had to contest as an independent candidate from Muzaffarpur, but forfeited his deposit. The ignominy was further compounded when Nitish Kumar offered him a Rajya Sabha seat in consolation for his humiliation.

The journey of an intrepid young Christian boy from Mangalore, who captured people’s imagination in the ’70s and ’80s, ends on a rather tragic and sombre note. He leaves behind a legacy which is neither politically inspiring nor personally worth emulating. But there is no doubt that the story of Fernandes’s life is extraordinary in every sense of the term. Enamoured of an ideology that promised a utopia, Fernandes seemed to have lost his way in the web of deceit and personal ambitions created around him.

When he was substantially gripped by Alzheimer’s, his wife, Leila Kabir, once took him to his friend LK Advani to give him some diversion. Fernandes showed no signs of recognising Advani. The veteran BJP leader rued, “George, I find it sad that now you don’t recognise me.” Fernandes’s eyes suddenly flickered and he mumbled, “Lal-ji” (as Advani was referred to by his friends). This pleasure was momentary as Fernandes again slipped deep into the dark crevices and alleys of the human psyche from where it is impossible to get out. No doubt, Fernandes’s story is an incredible depiction of human capacities and vulnerabilities.

Ajay Singh is press secretary to the President of India