In almost all his earlier films, Ratnam has taken a wafer-thin plot from the epics or contemporary society and built a compelling human drama around them. However, in Ponniyin Selvan: I, he forcibly condenses the 2,210 pages from Kalki’s work, and refuses to interpret the story or make it his own.

In almost all his earlier films, Ratnam has taken a wafer-thin plot from the epics or contemporary society and built a compelling human drama around them. However, in Ponniyin Selvan: I, he forcibly condenses the 2,210 pages from Kalki’s work, and refuses to interpret the story or make it his own.Mani Ratnam’s Ponniyin Selvan: I might have got the nod of approval from ardent fans of Kalki Krishnamurthy’s novel for staying true to the written material, but for an average cinephile, the film is a disappointment. The filmmaker has passively condensed the original five-part novel on the early days of Chola prince Arulmozhivarman. And presented them as passionless, bulleted data points that fall flat. The film is not necessarily bad, but it is bland and the primary reason for ’s blandness lies in its unwavering faithfulness to Kalki’s novel. Unable to think beyond the boundaries of its written structure, Mani Ratnam mimics the novel’s form on-screen and leaves us indifferent to his mammoth effort. So even at its best, Ponniyin Selvan: I only comes across as a sincere summary of the novel, but without achieving any cinematic quality. This is rather surprising because irrespective of how good or bad his earlier films were, Ratnam has attempted to push the boundaries of cinema in almost every one of them.

This brings us to the eternal debate of whether novels and short stories can justifiably be converted into cinema. Some believe that short stories can be convincingly made into feature films and novels are better suited for web series. But in both cases, it has to be understood that storytelling through the written word and celluloid are fundamentally different. While literature allow readers to pause, imagine, reflect and internalise at their own pace, in cinema, the pace and imagination of storytelling are entirely determined by the filmmaker.

This fundamental difference means that great cinema can emerge from novels or short stories only when filmmakers don’t try to literally replicate them. They could borrow the core elements from the textual material but it is important to be disloyal to its structure. And even be treacherous if necessary.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) makes for great cinema. And the 1977 novel by Stephen King on which it was based was a bestseller too. But still, King hated the film for how Kubrick had interpreted his novel. Even in the case of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where both the novel and film were developed concurrently by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke from the latter’s short story The Sentinel (1951), the film and novel turned out significantly different. This was again because of how Kubrick worked with the possibilities and limitations of the visual medium.

Closer home, writer Poomani’s terrific novel Vekkai was adapted by filmmaker Vetrimaaran as Asuran (2019). The film turned out to be a gripping drama and was a huge blockbuster. While Poomani welcomed the filmmaker’s attempt to adapt his novel, he still rejected it for how it was interpreted. As we can see, authors are often never happy with how their stories are adapted into films. That’s primarily because of how their original intent is drastically modified by the filmmaker.

Ratnam is, of course, not someone who might be unaware of all this. He has often interpreted stories from the Mahabharata and Ramayana for the screen. In his super hit film Thalapathi (1991), he narrated the story of the friendship between Karna and Duryodhana. But Thalapathi was an interesting underworld interpretation from contemporary times and not a faithful adaptation. In the film, Ratnam even goes to the extent of altering Karna’s fate and allowing him to live with his mother Kunti. And it is quite possible that the epic’s writer Vyasa might not have been too happy with such meddling.

But then, that is how great cinema is born — when filmmakers interpret short stories and novels through their own sensibilities and imagination and when they choose to be inspired by the novel but are still not afraid to breach its boundaries.

In almost all his earlier films, Ratnam has taken a wafer-thin plot from the epics or contemporary society and built a compelling human drama around them. It’s almost as if the human conflict is viewed through a magnifying glass. However, in Ponniyin Selvan: I, he forcibly condenses the 2,210 pages from Kalki’s work, and refuses to interpret the story or make it his own.

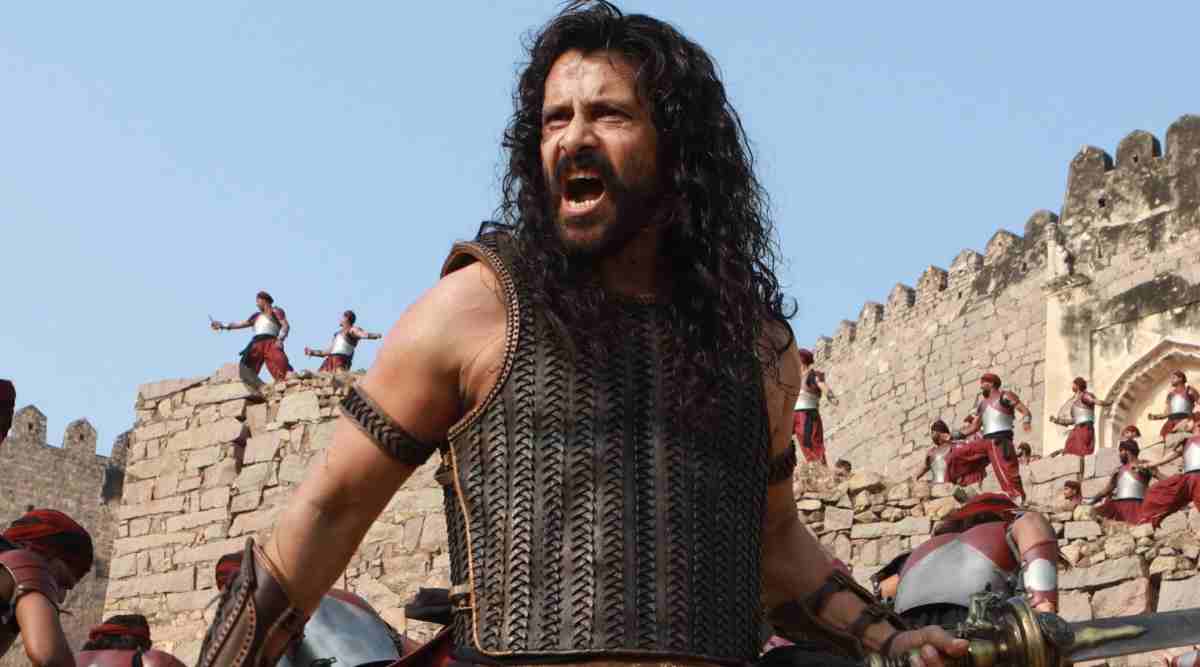

Even the characters and their motives as passed on to us as pieces of information than as emotional states. Aditha Karikalan’s heartbreak and aggression never convince us. Instead, actor Vikram’s performance makes us feel that Karikalan might just be another generic man-child. Similarly, Nandhini’s seductive manipulation was hardly felt through Aishwarya Rai’s performance. Instead, Ratnam seems satisfied with lighting her face like in a jewellery advertisement to convince us of her beauty. In terms of staging, performance and directing, Ponniyin Selvan: I might be the weakest in Ratnam’s filmography.

And in his overwhelming reverence for the author and his popular novel, the filmmaker chooses to be painstakingly and painfully faithful to it. And in the process, has delivered a film that resembles a stenographer’s shorthand of a fascinating speech. The stenographer might be able to cover all the key points from the speech. But not its emotion, thrills or magic. Ponniyin Selvan: I might have been made earnestly, but as a film, it ends up being dull and boring.

The writer is a Chennai-based writer and filmmaker