Devotees take the Goddess across the Hoogly, where she will be worshipped at the local barowari puja. (Credit: Partha Paul)

Devotees take the Goddess across the Hoogly, where she will be worshipped at the local barowari puja. (Credit: Partha Paul) On the way to Guptipara, a small town in Hooghly district, some three hours away from Kolkata, the white kash phool (flower) (Saccharum spontaneum) are in full bloom, signalling that the autumn festival of Durga Puja is just around the corner. Among the oldest towns in Bengal, Guptipara, is best known for its Vaishnava terracotta temples and gupo sandesh, one in the many kinds of mishti found in the state. But what is less well-known is that this town also gave the world Durga Puja in its most well-known form: the barowari puja or the community Durga Puja.

The origin of the barowari puja started way back in 1759. A community leader and a resident of Guptipara, 52-year-old Subrata Mondal’s research led him to a handful of old books that documents the town’s history when it was still a village, written by local historians, one of which is Nrishingha Prasad Bhattacharjee’s book, Guptipara’s True Story & the First Barowari.

One of the stories surrounding the origins of this form of the festival says that in 1759, when a group of women from the village went to a zamindar bari (house) to pray, they were made to leave, perhaps because the family was unwilling to permit outsiders to pray inside their home. Angry at the perceived insult, the men in the village decided to hold their own puja where the community could pray.

It is difficult to identify the zamindar bari in question because it does not find mention in available archival records. Just a stone’s throw from the location believed to be where the first barowari puja started, is the imposing approximately 400-year-old Sen bari, built in pre-British architecture in the Murshidabad style, which some believe is the zamindar bari where the conflict first occurred in the mid 1700s.

Mondal believes that there is little authenticity to claims that the villagers were made to leave the Sen zamindar bari, but that has done little to put a stop to the myths surrounding the incident. “It was the nearest home to the location,” says Mondal, which has resulted in people propagating the legend.

A descendant of the Sen zamindar family, 71-year-old Anjan Sen, grew up hearing a different version of the story. “We have been told that villagers were always welcome to the house and participated in the rituals. But this narrative that women of the village were barred from praying and thus had to go outside and start their own puja is not accurate,” says Sen.

“Over the past decade, we started hearing this story, peddled by people who still live in Guptipara,” says Sen. Soon, what the family firmly believes to be a myth, took on a life of its own, and was reproduced by newspapers, televisions news broadcasts and travel bloggers.

The oldest part of Anjan Sen’s ancestral home in Guptipara, built in pre-British architecture in the Murshidabad style. (Credit: Anjan Sen)

The oldest part of Anjan Sen’s ancestral home in Guptipara, built in pre-British architecture in the Murshidabad style. (Credit: Anjan Sen) Sen points to the prayers and rituals of the festival when it is held within raj baris (royal houses) and zamindar homes, where outsiders don’t typically participate intimately in the preparations of the puja. “Outsiders are welcome to visit, but they don’t really participate in the rituals. Our family records don’t indicate that we had any dispute with villagers or that an incident like this happened,” Sen says.

While the circumstances surrounding the incident that eventually led to the start of the barowari puja are unclear, what is not in dispute is that it started in the village of Guptipara 263 years ago.

One of the earliest written records in English can be found in an article published in the May 1820 edition of the newspaper The Friend of India, a predecessor of The Statesman. “A new species of pooja which has been introduced into Bengal within the last thirty years called Barowaree. About thirty years ago at Guptipara near Santipur town, celebrated in Bengal for its numerous colleges, a number of Brahmins formed an association for the celebration of a pooja independently of the rules of the Shastras,” says The Friend of India article.

The report delves deeper into the formation of the barowari puja and how the villagers of Guptipara eventually succeeded in setting it up, and creating a blueprint for what is recognised as the barowari puja today. “They elected twelve men as a committee, from which circumstances it takes its name and solicited subscriptions in all surrounding villages. Finding their collections inadequate, they sent men into various parts of the country to obtain further supplies of money, of whom many according to current report have never returned.”

Sen believes the villagers of Guptipara, who set out to solicit donations possibly travelled across modern-day Hooghly district and undivided Bengal province in pre-Independence India, created the concept of soliciting chaanda that is still in existence today. “Having thus obtained about 700 rupees they celebrated the worship of Jugudhatree for seven days with such splendour, as to attract the worship from a distance of more than a hundred miles,” The Friend of India article says.

The villagers, unable to celebrate Durga Puja the way they wished to, marked the next festival that appeared in the Bengali calendar: that of Jagaddhatri, an avatar of Durga, whose festival comes approximately a month later.

While travelling across villages to collect donations, the villagers also spread word of their cause, inspiring others across towns and villages of Hooghly, such as Bandel, Chandannagar and Krishnanagar, to visit Guptipara’s barowari puja and start their own.

“The formulas of worship were, of course, regulated by the established practice of the Hindoo ritual, but beyond this, the whole was formed on a plan not recognised by the Shashtras. They obtained the most excellent singers to be found in Bengal, entertained every Brahmin who arrived and spent the week in all the intoxication of festivity and enjoyment. On the successful termination of the scheme, they determined to render the pooja annual, and it has since been celebrated with undeviating regularity,” says The Friend of India article.

By the turn of the century, the concept of the barowari puja had reached the city of Calcutta, where it evolved further. The first puja in the city started in the 19th century, in the locality where the neighbourhood of Kalighat and Bhawanipore meet, near the Adi Ganga, off Balaram Bose Ghat.

Inadvertently, the barowari puja and its popularity also provided an impetus to the artisans of Kumartuli, who made idols of the goddess and her family, generating more opportunities for their craft and subsequent income.

Still, it would take another century for the barowari puja to be entirely open to the public. “It was only in the twentieth century with the establishment of sarbajanin puja that the festival culture became public and the goddess travelled from the parlour to the streets,” write Knut A Jacobsen and Kristina Myrvold in their book Religion and Technology in India Spaces, Practices and Authorities (Routledge, 2019).

“The word sarbojanin (for all men) came to be substituted for barowari at the time of the Indian National Congress (INC) held in Calcutta in 1910,” write authors Subhayu Chattopadhyay, Bipasha Raha in their book ‘Mapping the Path to Maturity A Connected History of Bengal and the North-East’ (Routledge , 2017), where this form of puja was used as a nationalist forum in religious guise.

Today, many across West Bengal and elsewhere where Durga Puja and other forms of the goddess are worshipped through the year, interchangeably use ‘barowari’ and ‘sarbojanin’ to indicate the communal nature of the festivities.

Bidhyabashini Barowari tola in Guptipara, West Bengal. (Credit: Neha Banka)

Bidhyabashini Barowari tola in Guptipara, West Bengal. (Credit: Neha Banka) Back in Guptipara, the location where the first barowari puja started is now identified as the Bidhyabashini Barowari tola, named after the goddess Jagaddhatri who is worshipped here in the avatar of Bidhyabashini. The term ‘tola’ is a Bengali word for the location where a deity’s idol is placed.

Diverging from the standard features and colours of Durga idols most commonly seen in Bengal and in those created by artisans from the state, this idol is painted vermillion. Like many others familiar with the town’s association with this form of puja celebrations, Sen and Mondal are almost tired of correcting people: “It is a misconception that the concept of barowari puja started with Durga Puja. It started with Jagaddhatri Puja and then became widely adopted for other festivals, especially associated with the goddess,” says Sen.

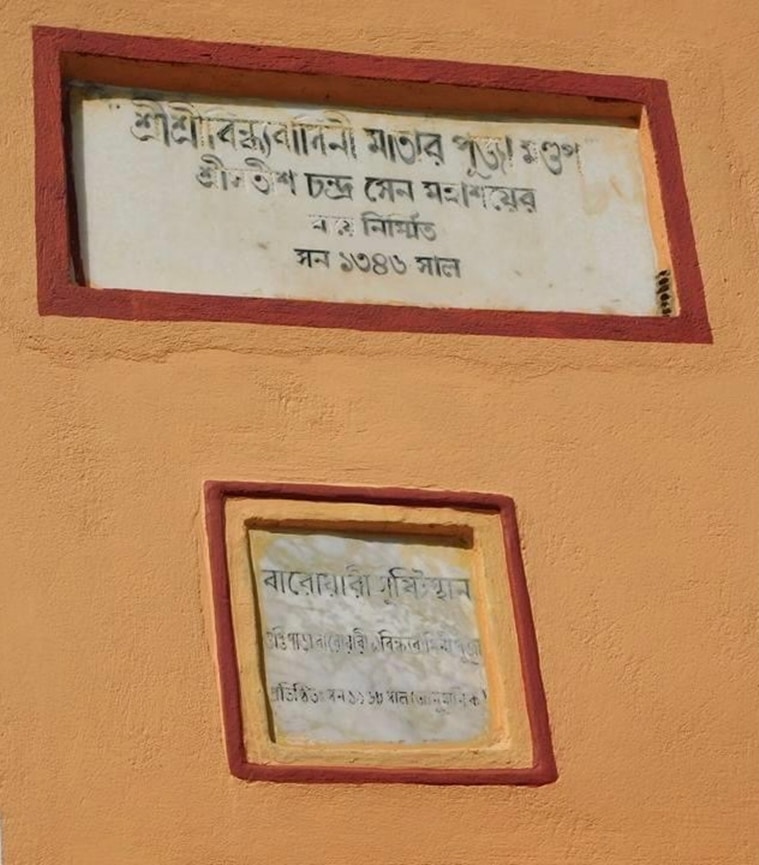

A plaque on the Bidhyabashini Barowari tola in Guptipara. (Credit: Neha Banka)

A plaque on the Bidhyabashini Barowari tola in Guptipara. (Credit: Neha Banka) When the Bidhyabashini Barowari tola’s grounds are not filled with devotees lining up to offer prayers to the deities, it would be easy to overlook the structure located deep inside a narrow bylane, surrounded by homes on all sides in the small town. On the tola’s orange facade, two small white plaques with inscriptions in Bengali provide some more information about the site’s history. The first plaque reads: A member of the extended Sen family, Satish Chandra Sen, provided the funds required to establish what forms the exteriors of the Bidhyabashini Barowari tola in 1939. The second plaque says: “The site where the barowari was created. Bidhyabashini devi’s puja. Established in 1116”, in the Bengali calendar.

Though many may not be acquainted with the back story to barowari puja, it’s good to remember that nearly three centuries ago, 12 men of Guptipara had set off to make the festival more accessible for the village, and inadvertently created a blueprint for a festival of bonhomie and extravaganza that would become its most common, recognisable and accessible form, not just in West Bengal, but across India.