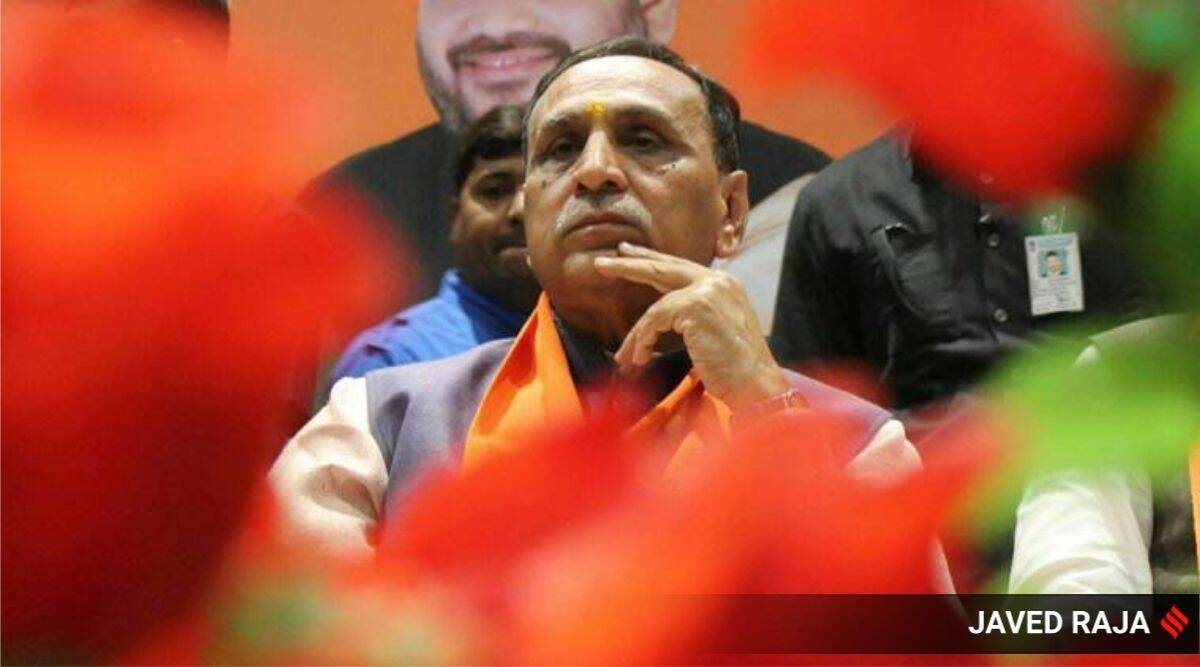

When he exited last year, Rupani had said “such smooth changeover is only possible in the BJP. It is not possible in the Opposition”. (Express Photo by Javed Raja)

When he exited last year, Rupani had said “such smooth changeover is only possible in the BJP. It is not possible in the Opposition”. (Express Photo by Javed Raja)Former Gujarat chief minister Vijay Rupani’s remark in an interview to The Indian Express comment that the “high command” was supreme in the party and that the legislature party meeting before announcing the CM was “merely a procedure” simply places on record what has been followed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) almost since its inception in the 1980s and is seeing a loose adaptation in parties like the Congress, which had claimed to stand for upholding democratic traditions.

The “high command” remains a lordly body that is largely inaccessible to the ranks, in a strictly hierarchical, cadre-based party like the BJP. Usually a mix of members with roots in the RSS, which is the ideological parent body of the BJP, and the party, it thrives on the unquestioned loyalty of the ranks.

The BJP derives its confidence and its strength from the fact that nobody challenges the high command. Thus, when the high command chose to end Rupani’s term last September, with a year to go for the assembly elections and brought in a brand new ministry which included many who had never held portfolios, there was not even a whimper. Some outgoing ministers sulked, but that only delayed the swearing-in ceremony, and did not disrupt it.

Contrast this with what happened in the Congress-ruled Punjab at the same time last year, when Captain Amarinder Singh was replaced as chief minister with Charanjit Singh Channi. And to what is now happening in Rajasthan where the incumbent chief minister, Ashok Gehlot, appears to be in defiance of the party high command.

The BJP prides itself on the absence of such questioning and overt dissent. There have been aberrations, of course, with leaders who have a strong following, who have won elections on their own strength, but the high command has always prevailed. The chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, Yogi Adityanath, is one such aberration.

In Gujarat, traditionally, it was the organisational general secretary in charge who was the most powerful, took most decisions and was the connection between the party and the government. This was a position once held by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, when Keshubhai Patel was the chief minister. Then, Modi was often referred to as the “super chief minister”. However, the party got a jolt when Shankersinh Vaghela broke ranks to topple the BJP government, launch his own party and form a government.

Wiser from the Vaghela revolt, the BJP has firmed up its structure making its “high command” stronger. No chief minister in Gujarat, after Modi, however, has been able to completely come into their own.

Congress, which has seen at least three successful breakaway groups forming governments or being part of it — Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), Trinamool Congress and the YSR Congress Party — is currently gripped with dissent not just from the G23, but even from leaders perceived to be loyal to the Gandhi family, which threatens to disrupt even the “democratic” process of electing a party chief.

Article 164 of the Indian Constitution empowers the governor to appoint the chief minister, with other ministers appointed by the governor “on the advice of the chief minister”. This, however, is normative. The legislature party meetings to elect the CMs have become a formality. Usually, the outgoing CM is made to “propose” the name of the new CM, which is already decided by the high command, and the MLAs second the proposal to make it look unanimous. In the Congress, this authority played out differently when it won Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan in 2018 and entrusted the decision of choosing the CM to Rahul Gandhi.

When he exited last year, Rupani had said “such smooth changeover is only possible in the BJP. It is not possible in the Opposition”.

In the BJP, such “high commands” exist even at the level of the local bodies like municipal corporations, who have the final word on which projects and schemes should be pushed. They comprise functionaries from the party’s state organisation, who became a link between the state government and the local body. The process, though authoritarian, gave a semblance of discipline.

Veteran BJP leaders will tell you how a “co-ordination committee” of party of office-bearers with roots in the RSS, and the government largely comprised the “high command” but the definition remains vague and has now metamorphosed to becoming the voice of some dominant individuals, riding on the sentiment of “ours not to reason why” from the rank and file.

As a former BJP leader puts it: The BJP is an “emotion-driven” party while the Congress has people with “logic and intelligence”. Between the two, the fragility or strength of democracy is being put to the test.

leena.misra@expressindia.com