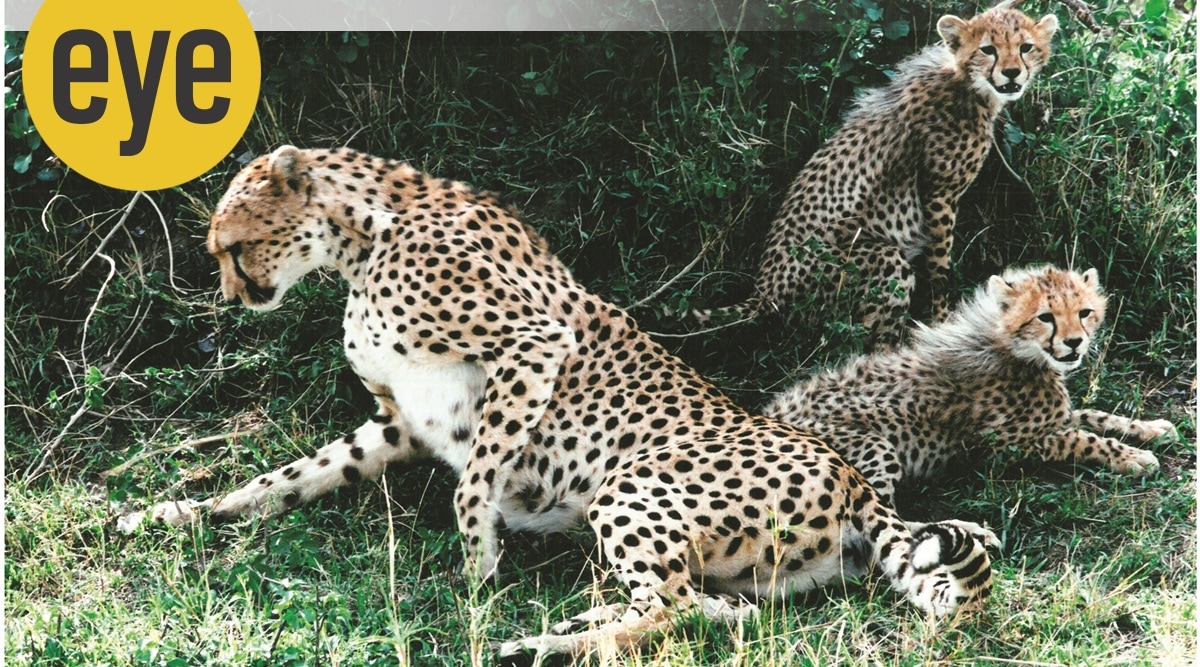

Cheetah with cubs in Kenya’s Masai Mara (Courtesy: MK Ranjitsinh)

Cheetah with cubs in Kenya’s Masai Mara (Courtesy: MK Ranjitsinh)From a cushion cover to a photograph to a figurine, all of which share space with other wild things, the cheetah lives on in every corner of MK Ranjitsinh’s living room in Delhi. Much like it has lived in his imagination ever since he was a boy of 10 or so. “As a boy, I had heard that the last cheetah had been shot and this must have been in either 1948 or 1949. I was an avid reader of wildlife literature and I thought why can’t we bring the cheetah back from somewhere. It was a dream and it’s now come true. I always say the most difficult thing to kill is a good idea,” says Ranjitsinh, 84, who belongs to the royal family of Wankaner in Gujarat and who made bringing cheetahs to India his life-long mission.

As eight cheetahs from Namibia make a new home in Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh, the state where Ranjistsinh served as an IAS officer and where he set up a number of sanctuaries and national parks, including Kuno in 1981, he has finally seen his idea take shape. Twelve more animals are set to follow from South Africa soon.

The chief architect of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, Ranjitsinh included the cheetah in the Act even though the animal had disappeared from India by then. “If you would check the Act, which Indira Gandhi had put me in charge of drafting, in Schedule 1, the cheetah is already there though it was extinct. So, that was an assertion that the cheetah will one day come back, and then you won’t have to change anything in the Act for it,” he says.

In 1949, the Raja of Korea, in what is now Chhattisgarh, is said to have shot the last three cheetahs in India. However, even after 1949, there had been occasional claims of cheetah sighting, says Ranjitsinh, including one as late as 1958 from the Raja of Korea’s son. The cheetah, the fastest land animal in the world and the only large carnivore to vanish from India, was declared extinct in the country in 1952.

For centuries, cheetahs have fascinated people. In his book Tears of the Cheetah (2003), geneticist Stephen J O’Brien who wrote on why cheetahs have such little genetic diversity, says, “Regal potentates trained cheetahs as hunting companions, treasuring their predatory skills balanced by their timid acquiescence to captivity. King Tut’s tomb was decorated with numerous cheetah statues and war shields sheathed by cheetah skins. William the Conqueror and the Mogul emperor Akbar kept cheetahs for sport hunting. In the chronicles of his Oriental adventures, Marco Polo reported that the Chinese emperor Kublai Khan kept over one thousand cheetahs in his summer palace at Karakoram.”

In India, illustrations document cheetahs in chains and in bullock carts being ferried as hunting companions. References to coursing with the cheetahs go back to the 12th century. Divyabhanusinh, who has been instrumental in the attempt to get the cheetahs to India, writes in his exhaustive book The End of a Trail: The Cheetah in India (1995), “While the Manasollasa records coursing with cheetahs as an established practice at Hindu courts of the 12th century, the various Muslim sources examined here prove the knowledge of the cheetah in North India and the Deccan among Muslim kings and courts, as well as the tradition of hunting with it as an established practice among them before the arrival of the Mughals.”

MK Ranjitsinh at his home in Delhi. (Credit: Anil Sharma)

MK Ranjitsinh at his home in Delhi. (Credit: Anil Sharma) The reasons for its extinction in India were many — over hunting, habit loss, decline in prey base, grasslands being converted into agricultural land. It was in 1972, shortly after the WPA was drafted, that Ranjitsinh, as director, Wildlife Preservation of India, negotiated with Iran for cheetahs in exchange of lions. The plan fell through in the following years as the politics changed in both countries: the Shah of Iran was deposed in 1979 and in India, Indira Gandhi declared Emergency in 1975. Iran, which now has the only population of Asiatic cheetahs, has seen a steady decline in numbers, making an exchange impossible. The global population of cheetahs today stands a little over 7,000. “Cheetahs are believed to have evolved in southern Africa and then walked northward and then eastward across Asia,” says Ranjitsinh. While the ecological separation between Asiatic and African lion is estimated to have occurred about 100,000 years ago, that between the African and Asiatic cheetah is believed to be only 4,500 to 6.500 years old. So, he says, the African cheetah seemed the best option to be brought to India.

In 2009, the plan to reintroduce the cheetah was revived. An international meeting was convened in Gajner in Bikaner, which was attended by experts from South Africa and Namibia and concluded that cheetah reintroduction was feasible. Then environment minister Jairam Ramesh gave him directions to prepare a detailed roadmap and under the supervision of YV Jhala of the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, a research team surveyed seven potential sites to conclude that Kuno had the best potential. Kuno had earlier been readied to establish a second home for the lion but Gujarat has till date refused to let the lions go out of the state. “I am from Gujarat too, but it’s parochial to hold on to the lions,” says Ranjitsinh.

But the lion-ready park with its grassland-cum-forest mosaic, he says, is also an ideal habitat for the cheetah. As he writes in A Life with Wildlife: From Princely India to the Present (2017), “In fact, this region had been prime cheetah habitat and a principal site for their capture in the Mughal era.” “Kuno was found suitable for the lions, and its habitat has improved but nothing happened. Then, when the lions did not come, we said the lion can always come, you can first bring in the lesser predator.” In 2011, the MoEF constituted a task force for the reintroduction of the cheetah in India with him as chairman. But, in 2013, the Supreme Court called the proposed plan to reintroduce the cheetah illegal. “The court passed this order that the lion will come to Kuno and not the cheetah. But the lion has still not come. And the cheetah could not come,” says Rajnitsinh. They drafted a review petition in the Supreme Court and, in 2020, the Court ruled that the African cheetah can come to Kuno. Ranjitsinh was appointed by the Supreme Court to chair an expert committee set up for the relocation.

The banks of the Kuno river that flows through the Kuno-Palpur National Park, Madhya Pradesh (Credit: Shahroz Khan Afridi)

The banks of the Kuno river that flows through the Kuno-Palpur National Park, Madhya Pradesh (Credit: Shahroz Khan Afridi) As the cheetahs finally arrive in India, Ranjitsinh acknowledges there are challenges. “Look, in all translocations, there will be casualties. Maybe, in release to the wild. They may be killed by a leopard, but doesn’t that happen in the wild? The cheetah has reached a saturation point in South Africa and they are not breeding them because they don’t have the space for them. Sometimes these things happen,” says Ranjitsinh, who saw his first cheetahs in the wild in Amboseli National Park at the foot of Mt Kilimanjaro in 1964.

The cheetah reintroduction plan is not without its critics who term it a vanity project, warn of conflict with humans and question the prioritising of the cheetah over the lions, whose growing numbers in Gir has led to their straying out and the threat of them being wiped out in the event of a disease. “I think this is deliberate obfuscation. Why not both? Of course, the cheetah will have to come first. They must have two litters before they become territorial and native to the place and then a larger predator can come. They may kill some but they will not drive them away. In Africa, they always do that. If you look at the Mughal records — of course it’s a bygone era and the situation cannot be the same — all four great cats lived in Kuno. So now the leopard is there, the cheetah is coming, and if the lion comes and an occasional tiger still walks in, nobody’s going to stop it. There will be no place like this in the whole world. That is my dream: all the four great cats of the subcontinent in the same spot. It may not happen in my lifetime, but it can happen some day,” he says.