Amlan Borgohain, India's fastest man, is at a level where he is thinking of running under 10 seconds.

Amlan Borgohain, India's fastest man, is at a level where he is thinking of running under 10 seconds. The biomechanics of a bouncing tiger, one of the central characters in the popular fictional children’s series Winnie the Pooh, could help Indian sprinters run faster. Tigger, a close friend of the famous teddy bear, jumps without bending his knees. ‘Tiggers’ increase tendon strength and help a sprinter cut milliseconds.

The personal coach of India’s fastest man Amlan Borgohain says Indian sprinters are like gym rats who bulk up. But there isn’t enough focus on smart exercises like Tiggers.

Coach James Hillier specialises in sprints and hurdles. Before he moved to India nearly three years ago, he worked with England Athletics. Borgohain and Jyothi Yarraji in the 100 metre hurdles broke national records after Hillier took them under his wing. A sub-10 is Borgohain’s ultimate target. Hillier is a coach who believes an Indian can dip under 10seconds with a few tweaks.

Indian sprinters and hurdlers should be doing a lot more reactive-strength training, the coach says.

“A fault I see with Indian sprinters is that they spend too much time in the gym trying to get big. They focus on pure strength. You got to be light. To build reactive strength takes a long time. Reactive strength is how quickly you can strike the ground using your tendons more than your muscles. Tendons store energy more efficiently than muscles. Exercises for reactive strength would be like stiffness jumps. There is a little tiger in Winne the Pooh. He jumps up and down and does not bend his legs. So we call these stiffness jumps as Tiggers,” Hillier, the Athletics Director of the Reliance Foundation Athletics Programme, says.

The top international sprinters train in the hot weather of Florida, Texas and California. (Reuters)

The top international sprinters train in the hot weather of Florida, Texas and California. (Reuters) The coach gives another example of an animal to emphasise the importance of tendons. Not a tiger in a cartoon but a living mammal.

“A kangaroo has got really skinny legs which are pure tendons. But it is fast and springy. Developing tendon strength takes longer. You can get quick improvements in the gym and maybe you can run a little faster. But ultimately it will limit you. For me it is a long ball game. You have to build an athlete systematically over time. Amlan is still improving.”

Borgohain clocked 10.25 seconds at the All India Railway Championships meet in August to rewrite the national mark. Improving from 10.90 seconds, his personal best when Hillier started coaching him, to 10.25 took Borgohain two and a half years.

Hillier rattles off precise numbers.

“Obviously it is a great improvement. But relatively that (10.90 to 10.25) is easier than going from 10.25 to 9.99. He is now running seven metres faster than he was two-and-a-half years ago. To get him under 10 seconds, he has to go two and a half metres faster. Even though that is about a third of what he has already improved it is harder because of the law of diminishing returns. This is where coaches, facilities and sports science gets even more important,” Hillier says.

Borgohain is at a level where he is thinking of running under 10 seconds.

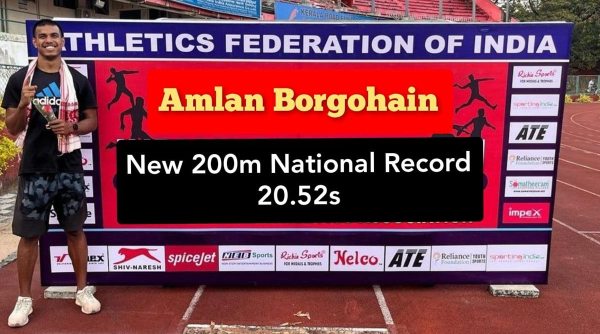

Amlan Borgohain clocks 20.52 seconds at the Federation Cup (Source: SAI Media/Twitter)

Amlan Borgohain clocks 20.52 seconds at the Federation Cup (Source: SAI Media/Twitter) An Indian running the 100 metres in a sub-10 second time seems like a flight of fancy because of the lag between them and elite sprinters.

The great Jesse Owens ran 10.2 seconds ninety years ago. In the late 1970s, after electronic timings were introduced, the fastest Indian was Gnanasekaran Ramaswamy (10.63 seconds). A decade earlier USA’s Jim Hines won the 1968 Olympic gold by clocking 9.95 seconds. Only 149 times have sprinters run faster than 10 seconds, a majority of them are runners of African origin.

Sprinters closer home breaking the 10-second barrier raise hope of more Asians entering the exclusive club.

China’s Su Bingtian.

China’s Su Bingtian. China’s Su Bingtian’s 9.83 at the Tokyo Olympics last year made him the fastest Asian. In 2009, when he was 20 years old Bingtian’s personal best was 10.28 seconds. It took him six years to clock 9.99 and become the first Asian-born sprinter to break the barrier.

In July, Sri Lanka’s Yupun Abeykoon’s 9.96 made him the first South-Asian to run faster than 10 seconds.

A sprinter from Kenya, a country known for its middle and long distance greats, is also making a mark. Ferdinand Omanyala posting the ninth fastest time ever (9.77) last year and winning the Commonwealth Games gold recently has put marathon-major Kenya on the spiriting map.

Borgohain wants to be the first Indian to break the barrier. Interviews of Bingtian are on his watching list. He has closely followed the Chinese man’s sub-10 journey. “I have watched his interviews and people used to say (to Bingtian) you can’t run, but he ran 9.83 seconds. If that man can do it why can’t we, it is just a matter of time. A Sri Lanka guy has broken the 10-second mark, so if I want to win a South Asian Games, I may have to break the 10-second barrier. It is getting harder and harder. It has always been about breaking the barrier. To go from 10.20 to 9.99 your race needs to be smooth and you need to have technical ability,” Borgohain says.

The start and the phase between 40 metres and 100 metres are Borgohain’s strengths. But he aims to be consistent when the gun goes off. “I don’t have control in my start, out of 10, I can do 5 or 6 well, but I want to make it 10 out of 10. First two steps I can be stronger and powerful,” Borgohain says.

Amiya Kumar Mallick, the fastest man before Borgohain, believes there exists a sprinting culture. “The number of entries is the maximum in sprints at national competitions even if athletes are charged a fee to participate. It is not that there are no quality sprinters. But there needs to be a constant belief in sprinters,” Mallick says.

Regular camps helmed by specialist coaches, sprint-training specific equipment, foreign exposure trips are the need of the hour, Mallick says.

“We are in a progressive phase, in the past six years since I had broken the record, many Indian sprinters have clocked 10.30. Preparing the fastest man needs a coach who has done research. I need a coach to tell me why my hand should move in a particular way. Here we have had coaches from Ukraine or the Russian bloc. We must get coaches from countries whose athletes are running faster… get a Jamaican or someone from the USA so our athletes can get educated on sprint technique,” Mallick says.

Indian coaches need to upskill for Indian sprinters to run faster. The books Hillier read as a young coach are not available to coaches in India.

“In India we have quite a few athletes running 10.3. The coaches are pretty good but they don’t have the experience of taking anyone past that. Maybe the facilities where they train are limited. I know some of the top sprinters in India, they tell me they live like an hour from the track and the facilities are not so good. You need world class facilities to get someone to run under 10 seconds. Su Bingtian was training at the Olympics Training Centre in Shanghai which has amazing training facilities. His coach Randy (Huntington) had everything. All the specialised weight training equipment they needed was imported from the US for him.”

Mallick trained using timing gates – beams projected from tripod-like stands to record accurate speed – in Jamaica in 2014. Indian sprinters have recently started using them in training sessions, he says. Malick feels like pulling his hair out everytime he shops for a good pair of spikes

“If you are ordering from the USA then you pay $120 for the shoes, another $120 for courier and the customs duty. I asked some friends (athletes) who went to Birmingham from the Commonwealth Games to get me a few pairs. Or I ask friends in IT abroad to get me a pair. You can’t order it like you order groceries in India. You can’t run below 10 if getting spikes is so tough,” Mallick says.

Former national 100 metre champion and Athletics Federation of India (AFI) president Adille Sumariwalla says Indians have the potential to clock 10 seconds.

However, grooming a pool remains a challenge for the AFI. Borgohain trains with hurdlers, including national record holder Jyothi Yarraji, at the Odisha Reliance Foundation High Performance Centre in Bhubaneshwar.

“We have a sprints programme in Bhubaneshwar. The AFI has signed an MOU with World Athletics and the high performance centre. Sprinters have consistently refused to join national camps. If they join camps they can also be dope tested regularly. Data shows the maximum number of dopers (in India) are sprinters. If we can find four to five young sprinters who clock 10.30 or below regularly and are ready to join the national camp, the AFI would be open to sending them abroad for training and exposure,” Sumariwalla says.

Green shoots of sprinting were spotted a decade back when the men’s 4×100 metre relay team won a bronze medal at the 2010 Commonwealth Games. One among the quartet Suresh Satya failed a dope test a few months later.

Sprinters being camp shy dates back to post-2010 CWG days. “Almost all the sprinters of the 4×100 men’s relay team which won bronze at the 2010 Games disappeared. The relay team could not repeat timings close to their best. We asked them to join the camp. There was a Ukrainian sprints coach. But just one or two did,” Sumariwalla recalls.

Once a group of sprinters train together, the next step for them should be competing abroad, Hillier advises. “If you look at someone like Su Bingtian and even Abeykoon, they compete overseas against the best athletes. They get beaten over there. Bingtiang used to come fifth or sixth in the Diamond League. But you need to get used to going overseas and see what the level is.”

Hillier also talks about ‘belief mechanism’, that infectious spirit which spurs sprinters to scale new heights.

“Mallick’s record has been living on borrowed time. Now that Amlan has broken it, others will believe they can also. I would love nothing better than other athletes to run 10.2 because I know it would make Amlan also run faster.”

Borgohain is inspired by a field event, the javelin throw and India’s star athlete Neeraj Chopra.

“Neeraj Chopra did it (win an Olympic gold). No one thought that Chopra could break 90 metres till a few years back. Now people believe he can. Then a Pakistan guy (Arshad Nadeem) broke the 90 metre barrier. So it is just about pushing each other.”