Union Minister for Commerce and Industry Piyush Goyal in a bilateral meeting with Japanese Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Nishimura Yasutoshi and others, on the sidelines of Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) Ministerial Conference, in Los Angeles, September 9, 2022. (PTI)

Union Minister for Commerce and Industry Piyush Goyal in a bilateral meeting with Japanese Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Nishimura Yasutoshi and others, on the sidelines of Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) Ministerial Conference, in Los Angeles, September 9, 2022. (PTI)INDIA’S DECISION to stay away from the trade pillar of the United States-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) ties in with an evolving consensus in New Delhi’s approach to global partnerships. This new consensus has some deepening gridlines: staying off multilateral trade pacts, sticking to bilateral deals that progressively build on an early harvest scheme; actively integrating into specialised global supply chain arrangements such as for rare earths or pharmaceutical ingredients; and restricting multilateral exposure to focused agreements such as tackling black money or cryptocurrency rules.

The backtracking on multilateral engagement on commerce comes at a time when trade statistics are beginning to turn inclement after a short, buoyant phase: the adverse contribution of net exports to real GDP growth — at minus 6.2% in April-June 2022-23 — was a record of sorts (the highest for the current GDP base series 2011-12), even as the country’s trade deficit narrowed slightly to $28.7 billion in August from a record high of $30 billion in the previous month.

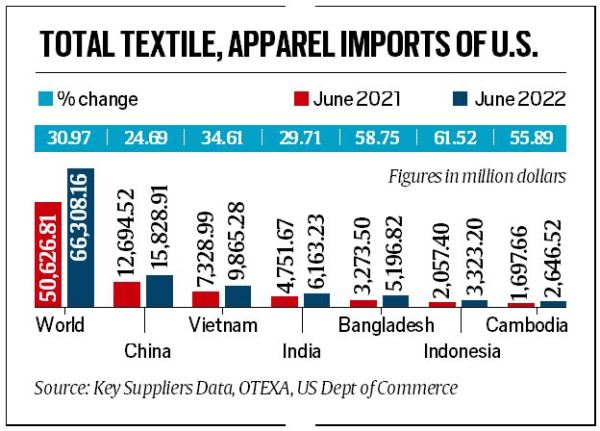

While the global slowdown is a key contributing factor, there are specific concerns too: India seems to be impacted more than others as the trade pie shrinks. For instance, in the key US market for textiles and garments, India’s growth in the first six months of 2022, while nearly 30 per cent, is the slowest among the top five exporters excluding China. Other key suppliers – Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia – are all doing way better, with India marginally trailing the average growth that all suppliers of textiles and garments into the US clocked over this period (see table).

Government officials rightly make a distinction between the IPEF and other multilateral trade deals that India has walked out of previously. “The IPEF is not exactly a trade pact and the provision of multiple pillars does entail an option to participants to choose what they want to be a part of. It’s not a take-it-or-leave-it arrangement, like most multilateral trade deals are,” an official said. The IPEF, launched at the recent Quad summit in Tokyo and being seen as the Joe Biden administration’s pivot to somewhat compensate for Washington’s exclusion from the revamped Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and a vehicle to re-establish American economic heft in the Indo-Pacific. Since the IPEF is not a regular trade pact, the 14 members so far are not obligated by all the four pillars despite being signatories. So, while staying off the trade part of the arrangement, India has joined the other three pillars of the multilateral arrangement – supply chains, tax and anti-corruption and clean energy.

Also, the IPEF envisages some degree of synergies with Quad members’ strategic priorities. “The IPEF does not incorporate issues such as tariff reduction or reciprocal commitments. India’s participation in the agreement was ensured by giving it flexibility in terms of which pillar it would want to join,” a retired government official said.

The onboarding of India’s concerns and flexibility on the IPEF comes after New Delhi, on the eve of the conclusion of the pan-Asian RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), announced India’s withdrawal from the agreement, amid concerns of a surge in imports from China. The IPEF engagement also comes at a time when India is attempting to find a place in the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), an ambitious new US-led 11-member partnership to secure supply chains of critical minerals, aimed at reducing dependency on China. India’s exclusion from the MSP is being seen as an exception in the otherwise upbeat spirit of cooperation with Washington DC – the IPEF being the latest plank after the Quad’s strategic focus and the new economic grouping alongside Israel, the UAE and the US – the I2U2 – that focuses on cooperation in health, water, transportation, food security, space and energy.

On the other hand, New Delhi’s outlook on bilateral negotiations appears to be remarkably upbeat: a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United Kingdom is expected to be concluded over “the next few weeks”, while talks with Canada are progressing well, according to government officials. This comes on the back of two trade agreements – one with the UAE and an early harvest deal with Australia – that have been signed over the last 12 months. India “is hopeful of concluding the negotiations for two more such pacts” by the end of this year, Union Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal was quoted by PTI as saying in Los Angeles Saturday after the IPEF deliberations.

Even as India charts its own unique course, the trade deficit continued to remain high in August. There are three broad concerns going into the Christmas season. One, the European Union, a key market, is headed into a sharp recession, triggered primarily by a worsening energy shock. Two, apart from the broader downturn in the global economy impacting outbound shipments, global buyers of goods from countries such as India are seeing deferrals in shipments of confirmed orders for Christmas. In the US – India’s single biggest market – the continuing inflationary pressure is quelling consumer demand and big box retailers are cutting back on inventories. Last, the increasing negative list for exports that now include wheat, steel and iron pellets etc has also impacted outbound shipments. Some varieties of rice have just been added to this list. All of this adds to the worsening balance of trade situation.

“Though the August print marks a moderation from July’s record trade deficit, the deficit remains at unsustainably high levels, and is likely to raise financing concerns,” Rahul Bajoria, chief India economist at Barclays Bank, said in a note. Bajoria forecast India’s current account deficit (CAD) could rise to $115 billion (or 3.3 per cent of GDP) in FY23.

There are some positives, though. FIEO President A Sakthivel said while exports have been impacted because of the headwinds in global trade and the inventories being high across the world, the demand for low-value products is increasing, helping India’s MSMEs. As buyers move away from China, both as the country is becoming costlier and less reliable with a zero Covid tolerance policy and as anti-China sentiments are gaining ground, there is a positive for India in the medium to long-term, he said.