At the centre of the book is a question: a certain kind of intelligence separates humans from all other animals, but is it also leading us to annihilation? (Representational image: Talia-Cohen via Unsplash)

“Another image comes to mind: Nietzsche leaving his hotel in Turin,” wrote the Czech author Milan Kundera in his 1984 book The Unbearable Lightness of Being. “Seeing a horse and a coachman beating it with a whip, Nietzsche went up to the horse and, before the coachman’s very eyes, put his arms around the horse’s neck and burst into tears.

That took place in 1889, when Nietzsche, too, had removed himself from the world of people. In other words, it was at the time when his mental illness had just erupted. But for that very reason I feel his gesture has broad implications: Nietzsche was trying to apologize to the horse of Descartes. His lunacy (that is, his final break with mankind) began at the very moment he burst into tears over the horse.”

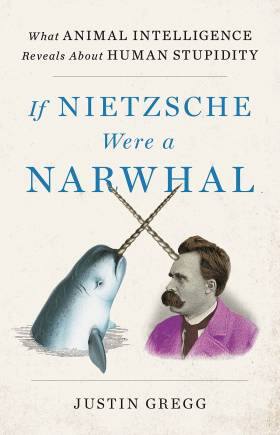

In the intriguingly titled If Nietzsche Were A Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity, author and scientist Justin Gregg begins where Kundera left off, with the philosopher Nietzsche, who believed animals did not “experience pleasure or suffering as deeply as humans” breaking down over the suffering of a horse.

In the intriguingly titled If Nietzsche Were A Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity, author and scientist Justin Gregg begins where Kundera left off, with the philosopher Nietzsche, who believed animals did not “experience pleasure or suffering as deeply as humans” breaking down over the suffering of a horse.

In the best tradition of “popular science” writing, Gregg, an adjunct professor of biology at St Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada, and an expert in dolphin communications, grabs this cognitive dissonance and runs with it, drawing on a vast body of research from medicine, animal behaviour, human behaviour, history, social studies and philosophy to explore a provocative question: a certain kind of intelligence separates humans from all other animals, but is it also leading us to annihilation?

The short, pessimistic answer is, yes. “If Nietzsche had been born a narwhal,” Gregg writes, “the world might never have had to endure the horrors of the Second World War or the Holocaust.” (Gregg quickly takes us through the history of Nietzsche and Nazism, pointing out that the philosopher himself hated anti-semites, but it was his ultra right-wing sister who appropriated, edited, manipulated and lied about his body of work after his death to make herself a favourite among the rising Nazis in the 1930s).

Gregg adopts a breezy, light-hearted style of writing in the book—Nietzsche is described in one chapter as a “hot mess”—to hold the reader’s hand gently as he explores some of the most complicated and difficult questions about the difference between human and non-human animal intelligence, with a pervasive sense of impending doom: animals have survived and thrived by relying on “learned association”—if a man with a stick beats a dog, the dog will learn that the stick signals impending violence—whereas the human spark, our evolution and eventual distancing from our animal ancestors began with our ability to pose and ponder the “why question.”

“These 'why' questions underpin our greatest discoveries,” Gregg writes. “Why is that star always in the same place each spring? Astronomy as a field was born. Why do I keep getting diarrhea when I drink milk? This was a question that probably kept Louis Pasteur up at night, leading to the discovery of pasteurization. Why does my hair stand on end when I shuffle barefoot across a rug? We now understand this as a result of a phenomenon known as 'electricity'. Why are there so many different plant and animal species? Charles Darwin had a good answer to this one (evolution). Anything we’ve held up as an example of our intellectual exceptionalism—and that differentiates our behavior from that of other species—has the deepest of roots in this one skill. Of all the things that fall under the glittery umbrella of human intelligence, our understanding of cause and effect is the source from which everything else springs.”

We are, unlike any other animal, “why” specialists. It has led us to build great cities, send ships into space, build MRI machines, create great works of art. It has also led to the atomic bomb, genocide, fighter jets, and the ability to wreak unprecedented havoc on nature—so much so that we now live in the Anthropocene Age, the time of human-induced change to the planet, where climate change and mass extinction of animals is no more a natural phenomena that occurs once in millions of years, but is being brought on directly by our actions.

A piping plover (Image: Mathew Schwartz via Unsplash)

A piping plover (Image: Mathew Schwartz via Unsplash)

For most people, this is now not a difficult concept to grasp. All we need to do is look at the news. Gregg’s book is very much a product of its time.

In seven quick chapters, Gregg unpacks a lot, and the book gets better as it goes along, becoming more and more thought-provoking. The stories he uses to illustrate his arguments become more interesting too: a personal favourite occurs in the chapter where Gregg is exploring the difference between animal deception and the human deception (human capability for deception and lying, is, of course, off the charts) and cites the example of the piping plover. If a piping plover’s babies are being threatened by a predator, she starts chirping to try and attract the predator’s attention, drawing it away from the children. When she has managed to do that, she suddenly flops to the ground at a strange angle, and begins to drag herself, as if she is injured and unable to fly. This signals to the hunter that she is easy prey! But as soon as the predator comes close, the mama plover flies away!

Another personal favourite, a chapter that will resonate with those who follow Buddhist philosophy, is the human awareness of mortality. Animals, it is widely believed, do not think about their own deaths. Humans, consciously or subconsciously, are obsessed with it. We fear it, we don’t want it, we imagine it, we envision it—death exists constantly as a spectre in our heads, and this, in itself, is the cause of so much grief, violence, and mental and physical illness. Buddhism engages with this very deeply, and one of its central teachings is on how to have a healthier relationship with the thought of our own mortality. Gregg posits that animals are, perhaps, far better off without this burden—it is one of the reasons they can live “in the moment”.

Gregg retreats from a sense of nihilism by offering some hope towards the end of the book—human intelligence is capable of great evil and destruction, but also of unmatched cooperation, empathy, and creativity. There may be a way out of self-destruction, if we have the courage to imagine and take that road. But meanwhile, we humans would do well not to consider our intelligence “superior” or revel in our “exceptionalism”. After all, we take great care to tend to our lawns, using means and resources that are contributing to the destruction of our planet.