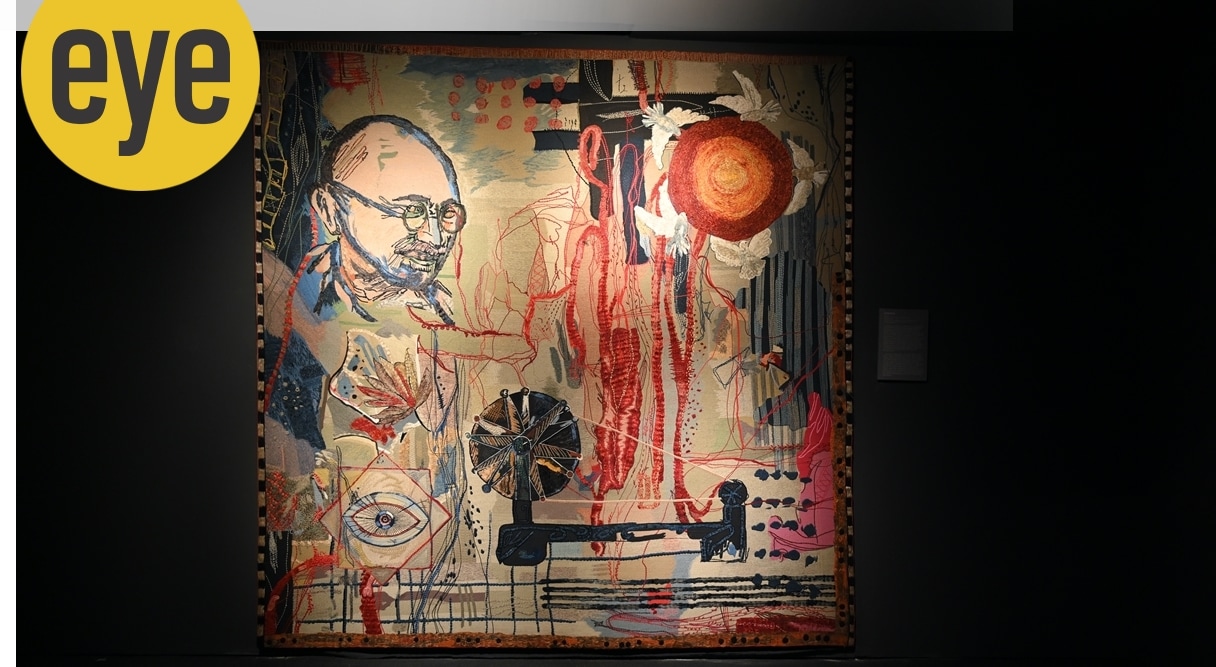

Freeway by Chanakya School of Craft. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation)

Freeway by Chanakya School of Craft. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation)When asked what would happen if specialists such as weavers and artisans fade away, German fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld was prescient in his observation. “There would be no haute couture anymore,” said the creative director of the French fashion house, Chanel.

Be it in the early 16th century when skilled needlewomen were taken to Portugal along with gifts for the Queen, or when textiles were one of India’s most popular exports, besides opium, indigo, and raw cotton in the 18th century, Indian craftsmanship have been famous for ages. An exhibition called “Sutr Santati”, organised by the National Museum, New Delhi, and the Abheraj Baldota Foundation, Karnataka, acts as a perfect showcase for India’s artisanal versatility. Textile revivalist Lavina Baldota has brought together over 100 exhibits of specially commissioned fabrics by skilled artisans, well-known designers and artists. Many of the exhibits are collaborative pieces with NGOs, designers and design institutions. As an ode to 75 years of India’s Independence, Sutr Santati (meaning the continuity of yarn) showcases themes, techniques and materials through the lens of innovation. The exhibition is on display till September 20.

Lavina Baldota, curator of Sutr Santati. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation)

Lavina Baldota, curator of Sutr Santati. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation) Many traditional techniques have joined hands with contemporary design, leading to statement art pieces in this exhibition. “Since the exhibition talks about the ‘then, now and next’, we were mindful of how our past informs us, how we work in the present and the possibilities of the fabric or the technique in the future. Can children of craftspeople take it forward or will youngsters want to explore it? So, I involved many students from design institutes across India in this exhibition, especially those who have worked with artisans. The idea of changing the associations of textile to art is not new, but the attempt was to collaborate and bring it to the fore,” says Baldota.

Mumbai artist Sukanya Garg, who has always worked with paper in the past, has used tie-and-dye on silk and collaborated with zardozi artisans from Kutch for the exhibition. Ahmedabad-based visual artist Jignesh Panchal, who has worked on canvas and cardboard before, has layered the art of pichwai on mashru. There are examples from Lucknow’s chikankari tradition, which shows 64 types of stitches on translucent muslin. Called “Shatranj”, the favourite game of the Nawabs of Awadh, the exhibit presents a variety of motifs through the geometric style of a chessboard. Then there’s the jamdani directory from West Bengal, which presents intricate patterns of the embroidery technique. While master weaver Balarama Krishnamoorthy from Kanchipuram shows 114 motifs of the weave on mulberry silk, Bengaluru-based Vimor Foundation brings the “Kanjivaram Gandaberuda and Yali”. The gandaberuda (double-headed bird) and yalli (griffin), done in red, black and gold, are salutations to the traditional weave yet present a contemporary aesthetic that moves from being just a textile piece to a work of art.

Sone Ki Chidiya by Pragati Mathur (left) and The Awakening by Gaurav Gupta. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation)

Sone Ki Chidiya by Pragati Mathur (left) and The Awakening by Gaurav Gupta. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation)

Also on display are textiles that have been woven, embroidered, resist-dyed, printed and painted. From Kala cotton to camel and sheep wool, goat and yak hair to lotus, banana and water hyacinth yarns, Baldota has taken forward the idea of “slow consumerism” as a way to be mindful of our environment, our society and ourselves. In doing this, she juxtaposes “the rural and the urban, the historical and the contemporary, the local and the global”. As a revivalist, Baldota agrees that such an endeavour is not without its challenges. Often reviving lost weaves is about finding the exact sample to recreate a piece. She gives the example of the Kodalikaruppur genre of textiles, which was worn by Maratha royals in the 18th and 19th century. Primarily used as saris or shawls, unlike the jamdani, the fine weave had a zari background and motifs were hand painted. The exhibit on display has replaced the hand painting with hand-block printing. “We were trying to create a reference for the genre. They used a particular red, which isn’t available now. In those days, the yarn, too, was different. The way we grow cotton has changed, so getting the base material itself has been a challenge. But with all its imperfections, I wanted to show it to present the struggle of such a work. Likewise, we have attempted work on himroo, a cotton-silk from Aurangabad, which needs revival,” she says, talking about how it is now done on modernised jacquard instead of being woven on the jala loom attachment.

Chandravali-Maratha miniature paintings recreated on fabric by Vinay Narkar, created by B.Venkatesh. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation)

Chandravali-Maratha miniature paintings recreated on fabric by Vinay Narkar, created by B.Venkatesh. (Courtesy: Abheraj Baldota Foundation) Over the years, numerous initiatives to revive Indian textiles have met with success, be it Martand Singh’s Vishwakarma exhibitions between 1981 and 1991, or more recently by Bengaluru-based Registry of Sarees, who collaborated with author and textile revivalist Malavika Singh to showcase 21 traditional drapes of India. Ahmedabad’s Calico Museum has been a repository of Indian textiles for over seven decades. “Sutr Santati” joins this illustrious lineage by putting the art and its artistes in the foreground of its narrative.

Baldota’s enterprise in bringing together fashion designers and weavers have led to some exquisite works at the show, that include Tarun Tahiliani’s take on Mata ni Pachedi, a hand-painted cloth made by the nomads from Gujarat’s Vaghari community, or Gaurav Gupta’s pashmina shawl that gets a contemporary spin with aari embroidery on the kundalini theme. That this exhibition mentions weavers by name, farming clusters where the yarn was procured and craft collectives, is reason enough to mark this as a show that cared for the hands that worked.