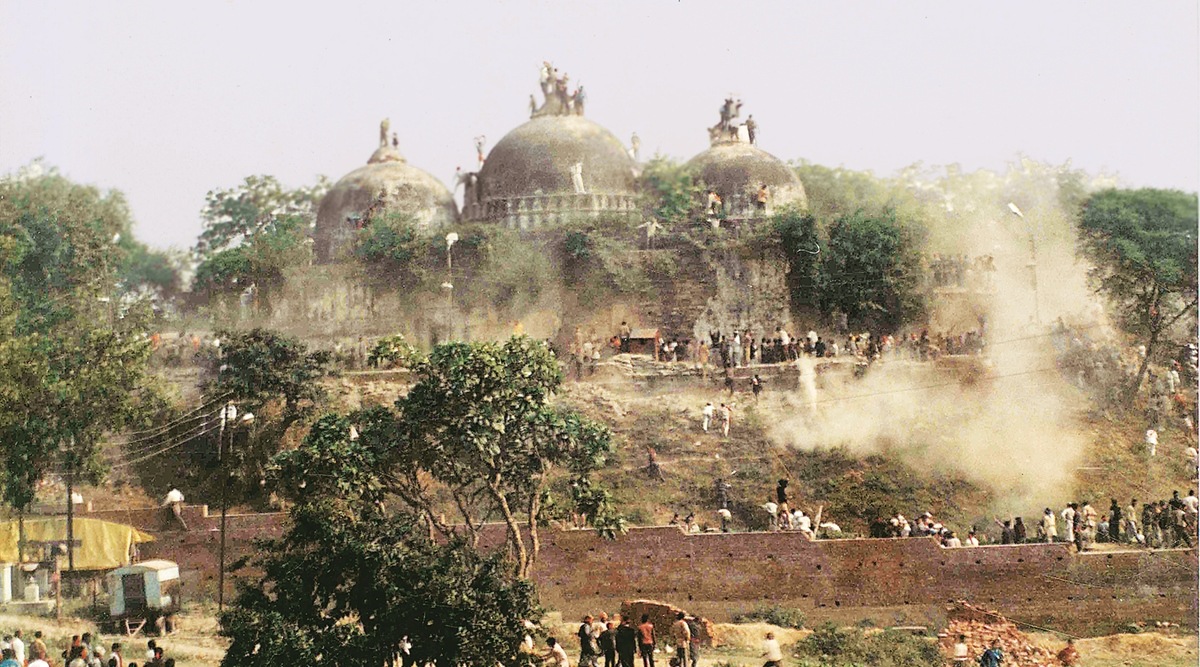

The contempt case for demolition was not listed once between 1994 and 2000. (File Photo)

The contempt case for demolition was not listed once between 1994 and 2000. (File Photo)Last week, the Supreme Court drew the curtains on nearly three-decade old contempt proceedings arising out of the 1992 demolition of the Babri Masjid against officials of the Uttar Pradesh administration and some Sangh Parivar leaders, saying nothing survives in the matter. With the petitioner Aslam Bhure and several respondents, including former UP chief minister Kalyan Singh, dead, the three-judge bench headed by Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul asked itself why “flog a dead horse”. In the same breath, the court admitted its own failure and said it was “unfortunate” that the case was not taken up earlier. The acknowledgement is a reminder of the judiciary’s role in the Babri demolition.

The contempt petitions against Kalyan Singh and several others were filed in April 1992, months before the demolition took place. Aslam Bhure, the petitioner, had been flagging snowballing activity on the disputed site. Lawyers who appeared in the case, including M M Kashyap, Bhure’s advocate, recall that the case was heard on a daily basis between September and November 1992. Many of those hearings incidentally happened in the same Court number 3 where the case was finally disposed of last week.

On November 28, 1992, in a judgment passed on a Saturday, the bench of Justices M N Venkatachaliah and G N Ray allowed what the Uttar Pradesh government called in sworn affidavits as a “symbolic kar-sewa” from 6-12 December that year. Letters from BJP MPs Swami Chinmayanand and Vijayaraje Scindia, along with an affidavit from UP’s Home Secretary, were submitted to the court, allaying fears of any construction activity. Attorney General for India K K Venugopal, who was then the senior advocate representing the UP government, told the court of the “markedly reassuring and eminently appropriate progress in the mood of the situation”. It had also relied on reports of its own observer who had faxed a report to the court that there was no construction material on the site.

Despite the assurances, when the domes of the Babri Masjid started falling under the watch of the state government on December 6, lawyers and journalists rushed to inform Justice Venkatachaliah. At 5 pm that day, an urgent sitting of the Supreme Court was held at the residence of Justice Venkatachaliah that went on till 9 pm. The allegations made by the petitioners were not disputed by the state governments lawyers Venugopal and Adarsh Goel (later Supreme Court judge and now Chairperson of the National Green Tribunal). Venugopal then withdrew himself from the case. But with then Attorney General Milon Banerjee informing the judges that President’s rule was imposed in Uttar Pradesh, the court concluded the order with a line that “no further orders are required”.

On December 18, the SC suo motu issued contempt notices and was in a hurry to hear the case. It took three months for Kalyan Singh and six other respondents to file their replies. But after that, the contempt petitions were not taken up by the court. With the case being initiated by the court itself, copies of the affidavits remained with the court alone. Meanwhile, Justice Venkatachaliah took over as the CJI and on his last working day, on October 24, 1994, delivered a judgment holding Kalyan Singh guilty of “flagrant breach” of his undertaking to the Supreme Court and sentenced him to a one-day imprisonment. This was for allowing a platform to be constructed despite the status quo order in July 1992. The same day, the SC, in a 3:2 verdict, upheld the constitutional validity of The Acquisition of Certain Areas of Ayodhya Act, 1993, under which the 67.703 acres of land adjoining Babri Masjid was acquired. Justice J S Verma wrote the majority opinion which included CJI Venkatachaliah and Justice G N Ray. The two minority judges — Justices Sam Piroj Bharucha and AM Ahmedi — had struck down the validity of the land acquisition.

The contempt case for the Babri demolition was to be “taken up later” but was not listed even once between 1994 and 2000. Case records show that the contempt petitions did come up for hearing once in 2000 but were adjourned. When Bhure died in 2010, his lawyers had no instructions to even seek a date from the court. By then, the title dispute of the disputed land reached the Supreme Court and the hearings took a new direction.

When asked why the contempt for Babri demolition was never taken up for hearing, Venkatachaialah had cited problems of the office of the CJI in prioritising cases for listing. Thirty years later, the case saw its day in court as CJI UU Lalit made a bid to solve the listing issue.

The case is a sobering reminder that the Supreme Court has not stayed away from the tugs and pulls of the political realities of the day. In closing the case without a hearing at all, the SC left many questions unanswered.