illustration by Mithun Chakraborty

illustration by Mithun ChakrabortyLike a cot in the living room

Gajadhar babu was looking at the things he had gathered in the room – two trunks, a basket, a bucket – when he spotted a box. That box wasn’t his.

‘Ganeshi,’ he called out to his help in the railway quarter. ‘What box is this, Ganeshi?’

Ganeshi was tying Gajadhar babu’s bedroll. He spoke with a mix of coyness, pride, and certain wistfulness.

Subscriber Only Stories

‘My wife has packed some ladoos for you, babu ji. She said that you like eating the ladoos she makes. Please keep these as a parting gift, babu ji. Who knows if we poor people would be able to serve you anymore?’

Gajadhar babu, who had been happy at finally returning , too was touched by sadness. It was as if he were leaving behind a familiar and convenient world full of love and respect.

‘Do remember us, babu ji.’ Ganeshi tied one final knot around Gajadhar babu’s bedroll.

‘Write to me if you need anything, Ganeshi,’ Gajadhar babu spoke softly.

‘Get your daughter married by December this year.’

‘Who would help us after you leave?’ Ganeshi wiped his tears with the edge of his towel. ‘Had you stayed here, we would have found some support.’

Gajadhar babu was eager to leave. That room in his railway quarter in Ranipur, in which he had spent so many years, was looking bare and ugly after his things had been removed. He had donated all the plants he had planted in the courtyard to his neighbours. There were fresh, gaping holes in places where people had uprooted the plants. The sight around him made Gajadhar babu sad, but the thought of living with his wife and children made that sadness crash like a timid wave.

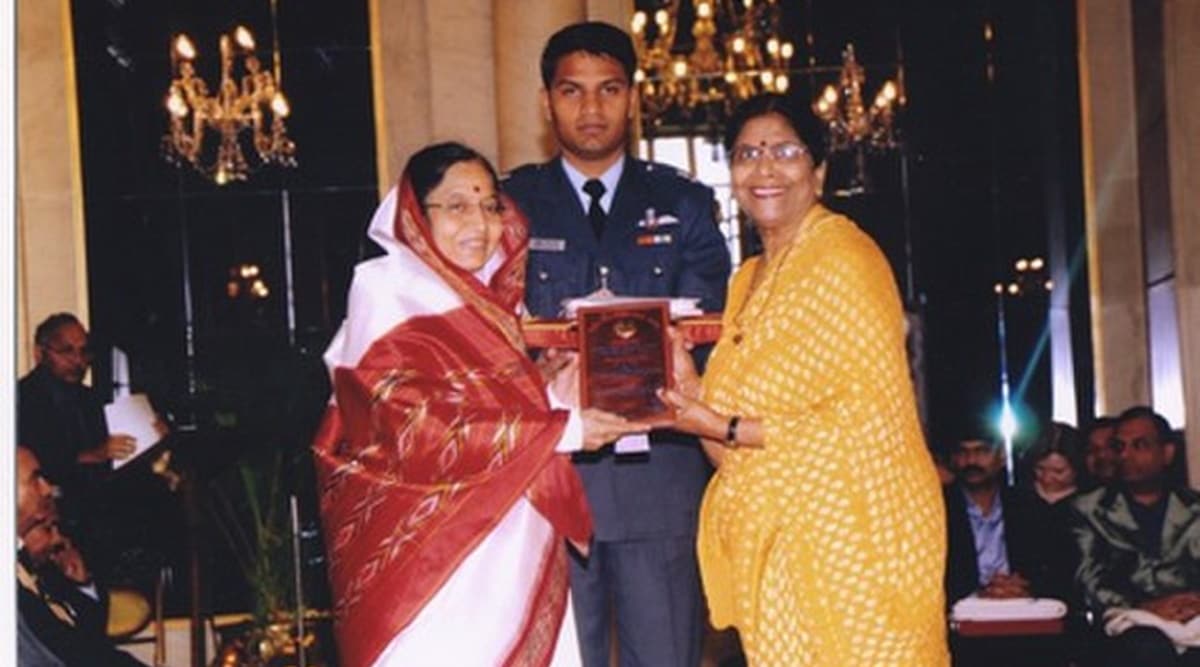

Usha Priyamvada (R) with former President of India Pratibha Patil (L) (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Usha Priyamvada (R) with former President of India Pratibha Patil (L) (Source: Wikimedia Commons) Gajadhar babu was happy. He was returning home after retiring from a job that had taken full thirty-five years of his life. He had spent a large part of these thirty-five years alone; and all that time he used to think about the day when he would be able to, finally, return to his family. That thought alone had made him strive and fight his loneliness. In the worldly way, Gajadhar babu’s life was one that people called successful. He had built a house for his family in the city. He had got his elder son, Amar, and elder daughter, Kanti, married to suitable partners. His younger son, Narendra, and his younger daughter, Basanti, who they lovingly called Bitto, were studying in college.

Gajadhar babu’s entire career had been spent at small railway stations. The places he had been posted at had lacked proper schools, so he had sent his wife and children to live in the city. Gajadhar babu loved his family very much and, of course, sought love in return. The decision to stay away from his family was a difficult one, but Gajadhar babu had to do it for the future of his children.

The railway quarters turned hard to live in after his wife and children left for the city. When his family had been with him, Gajadhar babu returned to a house full of love and laughter. He joked with his wife and played with his children.

Gajadhar babu wasn’t of a poetic nature, but he still remembered with love and tenderness all that his wife had spoken with him all those years ago. She used to keep the hearth burning till two in the afternoon, when he returned from work, so that she could serve him a hot meal. Even after he had eaten his fill, she would convince him to eat a little more and served him some more food. It was a request he had never been able to turn down. When he used to return home after some errand, she heard his footsteps and rushed out of the kitchen, her eyes lowered with shyness.

In his solitude, the memories of the time he had spent with his wife and children made Gajadhar babu nostalgic. Today, after so many years, he was going to reunite with his family, reunite with the love and respect he expected from his family.

Gajadhar babu removed his cap and placed it on his cot in the living room. Then he removed his coat and hung it on a nail on the wall. He could hear laughter in his house. It was a Sunday. His three children were having breakfast together. A smile perched over Gajadhar babu’s weary face. Holding that smile on his face, he walked towards his children.

Narendra was dancing, his hands placed on his waist, as Basanti doubled in laughter. Amar’s wife was so busy laughing she was unmindful of how she had tied her sari around herself. A stunned silence fell over the house the moment they spotted Gajadhar babu. Immediately, Amar’s wife covered her head with the end of her sari and Narendra sat down and placed a cup of tea to his lips. Basanti, however, was still

shaking in her chair as she tried to control her laughter.

‘So, Narendra,’ Gajadhar babu smiled, ‘which hero were you imitating?’

‘Nothing, Babu ji.’ Narendra couldn’t think of anything else to say. Gajadhar babu had wanted to be a part of that merriment, but he was

disappointed on seeing the entire house fall silent on his arrival. It was as if he were not expected there.

Sitting down, he told his daughter, ‘Basanti, give me some tea. What, your mother hasn’t finished her puja yet?’

Basanti looked towards her mother’s room and said, ‘She’ll be here shortly.’ Then she poured some tea in a cup and served it to her father.

Gajadhar babu took a couple sips and grimaced.

‘Bitto, this tea isn’t sweet at all.’

‘Give me the cup,’ Basanti extended her hand. ‘I’ll add some more sugar.’

‘No, that’s fine,’ Gajadhar babu refused. ‘When your mother makes tea for herself, I shall ask her to make some for me as well.’

Amar’s wife had already left the room. Narendra, too, slipped away unnoticed. Only Basanti remained seated with her father, perhaps because she felt it discourteous to leave her father sitting alone. A while later, Gajadhar babu’s wife came out of her room holding a lota filled with water to be poured on the tulsi plant. She was mumbling some shloka and Gajadhar babu could tell that she was mumbling the

shloka all wrong. Yet, Gajadhar babu’s wife went out, mumbling the wrong shloka, poured water on the tulsi, and came inside the house. The moment Basanti saw that her mother was with her father, she too vanished.

‘Arrey!’ Gajadhar babu’s wife looked around in surprise. ‘Why are you sitting alone? Where are the children?’

The question stabbed Gajadhar babu somewhere. He said, seemingly with great difficulty, ‘They must be busy in their work. They are children, after all.’ Gajadhar babu’s wife entered the kitchen and boiled over in anger on

seeing used, unwashed utensils spread all over.

‘This is an unholy house,’ she declared. ‘No use doing all this dharam-karam and religious things here. Even after doing my puja, I’ll have to touch these used utensils! No one is here to wash utensils!’

She called out to their domestic help. When that man did not reply, she hollered at him again. When the man did not reply even after being called twice, she turned towards her husband and said somewhat sheepishly, ‘Amar’s wife must have sent him somewhere—to the market, perhaps.’

Then she took a deep breath and fell quiet. Gajadhar babu remained seated, waiting for tea and breakfast. He remembered Ganeshi then. Before the arrival of the morning passenger train at the station in Ranipur, Ganeshi would be ready with fresh, steaming poori and jalebi that he cooked himself. After Gajadhar babu got ready for his shift, Ganeshi served him poori, jalebi, and a steaming tumbler of tea. And what a tea it used to be! Ganeshi made tea the way Gajadhar babu loved: three spoonful of sugar, served in a glass tumbler, with

a thick layer of cream at the top. The passenger train could reach Ranipur late, but Ganeshi’s tea for Gajadhar babu was never late.

In his own house, hearing his wife complain for nearly everything, Gajadhar babu was already filling up with bitterness.

‘The entire day is spent in this useless complaining,’ his wife’s muttering threw Gajadhar babu out of his memories of the breakfast Ganeshi used to cook for him. ‘I feel like I have wasted my entire life on this household. No one, just no one comes to help me a bit with the household work. I alone have to see everything.’

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar ‘What does Amar’s wife do?’ Gajadhar babu asked. ‘Keeps lying down the whole day,’ his wife said. ‘And this Basanti, if I tell her to do something, she immediately says that she has to go to college.’

Gajadhar babu, seeking to make life a bit easy for his overworked wife, called out to Basanti. Basanti came out of the room of Amar’s wife.

‘Basanti,’ Gajadhar babu told her, ‘from today, you will cook the dinner.

Your bhabhi will cook the lunch.’

Her father’s instruction came as a shock to Basanti.

‘But I have to study, Babu ji.’

Gajadhar babu looked at her lovingly.

‘You study in the mornings. Just see, your mother is not as strong as she

used to be. Think of her. You are here, your bhabhi is here. Both of you can do the

household work. This would take some burden off your mother.’

Basanti didn’t say anything. She stood before her father for a few seconds, but when he averted his gaze towards the kitchen, she left quietly.

‘She has nothing to do with studies,’ Gajadhar babu’s wife whispered to him. ‘The whole day she is busy with her friend Sheela. There are grown-up boys in Sheela’s house. Yet, our Basanti won’t stop going there. I’ve told her so many times to

not go to Sheela’s house, but will she listen? I’ll be relieved of my burdens the day we marry Basanti off.’

After breakfast, Gajadhar babu retired to his cot in the living room. The house was small and, over the years, while Gajadhar babu had been absent, things in the house had been arranged in such a way that now there was no space left in the house for Gajadhar babu to settle down. The chairs in the living room had been pushed against the walls and a small cot had been placed in the centre for Gajadhar babu, the way a temporary living arrangement is made for a guest. Gajadhar babu spent most of his time in that room and marveled at his temporariness. He thought of the trains which arrived at an interim station, stopped for some time, and then moved towards their actual destinations. What was his actual destination? Not this house, certainly. Even his wife, his own wife, did not have enough space in her room to offer

him shelter there.

Gajadhar babu’s wife had been given a small room in the house. A corner of that room was piled with jars of pickle, canisters of rice and dhal, and boxes of ghee. In the opposite corner, there were quilts for the winter, tied with thick ropes and packed neatly inside old dhurries. Another part of the room of Gajadhar babu’s wife was occupied by her own trunk and Basanti’s trunk. Apart from those two trunks, Gajadhar babu’s wife’s room had a huge tin trunk that held the winter clothes of the entire family. In the middle of the room, there was a clothes horse on which Basanti’s clothes were carelessly thrown. Gajadhar babu’s wife and Basanti had some space to sleep in the midst of all those odds and ends.

Gajadhar babu tried to never enter his wife’s room.

The other room in the house was occupied by Amar and his wife. The third room was towards the front of the house and was used as the living room. Before Gajadhar babu’s return, a set of three wickerwork chairs – a gift from Amar’s in-laws – had been installed in the living room. The chairs had blue seats and cushions embroidered by Amar’s wife.

Whenever Gajadhar babu’s wife had to draw the attention of her family to some complaint she had, she took a mat and spread it on the floor in the living room. And there she lay as long as her complaint was not heeded to.

One day, when she did the same drill, Gajadhar babu started talking with her about their family. He told her that he had been observing the way the household was being run.

‘We won’t have much money now,’ he said. ‘We should control our expenses.’

‘All expenditure is justified,’ Gajadhar babu’s wife said bitterly. ‘Where do I cut the expenses? I have grown old saving money for this family. So much that I never got to spend money even on myself. Nor could I wear the clothes I wished, neither did I buy what I had wanted.’

What his wife said hurt Gajadhar babu. Did his wife really say what she just said?

Gajadhar babu’s wife knew his position, how much money he earned, and how much he was capable of spending. He had expected his wife to mention the lack of money in their hands, but he hadn’t imagined her to be vocal and bitter about it. It would have satisfied Gajadhar babu had his wife asked him for suggestions to control their expenses. But his wife had complained, and it seemed that complaints

were all his wife was left with. That worried Gajadhar babu no end. He felt as if he himself were responsible for the misery his family had fallen into.

‘Amar’s mother, what do you lack?’ Gajadhar babu asked his wife. ‘You have two sons, there is a daughter-in-law. A person does not become wealthy by money alone.’

It was only after Gajadhar babu had said those words that he realised that those were his personal feelings, something that had come from somewhere within him. In her mood and the type of attitude she harboured, his wife could never

comprehend his words and she wouldn’t even try to. When Gajadhar babu realised

that, he felt very, very lonely.

And he was right. For his wife immediately snapped back.

‘Yes, such a nice daughter-in-law I have! She gives me so much

happiness! See, she has gone to cook our meal today. Do take note of what she ends

up doing.’

Saying this, Gajadhar babu’s wife turned to one side, shut her eyes, and soon fell asleep.

Gajadhar babu looked at his wife and wondered if she were the same woman who had placed her hands over his with love. Was she the same woman, in the memories of whose loving smile and kind words, he had spent his entire life? Somewhere, on that long road of life, that smiling, kind, sweet-natured, innocent young woman had been left behind. The elderly woman sleeping on a mat by his cot was someone unfamiliar, a stranger, someone who did not understand or even know how he was feeling. Deep in slumber, his wife’s corpulent body looked misshaped and ugly. No, she wasn’t the wife he had, the wife he knew. Gajadhar babu kept staring at his sleeping wife for some time; then he lay on his back and stared at the ceiling. Suddenly, something fell inside the house and the noise made Gajadhar babu’s wife wake up with a start.

‘Oh no! The cat must have entered the kitchen again.’ She got up with some effort and dashed inside the house. When she returned, her face was red and swollen with anger.

‘Go and see what your daughter-in-law has done,’ anger dripped from her voice as she spoke to Gajadhar babu. ‘She left the kitchen door open. The cat came and toppled over the entire bowl of dhal. It’s lunchtime now. What shall we eat? And you ask me what our daughter-in-law does! This is what she does.’ She plopped on her mat and began complaining again. ‘One tarkari and four parathas, this is all our daughter-in-law has cooked.

And she has wasted half a box of ghee! No value for things at all. The one who is earning is killing himself earning money, and the one who is spending is spending everything like water. I knew it. I knew that managing this household is not everyone’s cup of tea.’

His wife’s harsh words were grating on Gajadhar babu’s ears. He pressed his lips together and turned away from his wife.

Basanti, on her part, had cooked such a terrible dinner that it was almost inedible. Gajadhar babu, for the sake of family’s peace, ate his share quietly and left soon. But Narendra wouldn’t eat a second morsel. He pushed his plate away and stood up.

‘I can’t eat such bad food.’ Basanti pretended to be angry.

‘Don’t eat then. Who is asking you?’ ‘Who told you to cook?’ Narendra asked Basanti.

‘Babu ji told me,’ Basanti said. ‘These are the ideas Babu ji comes up with lying on his cot the whole day?’

Gajadhar babu’s wife intervened. She asked Basanti to leave, went to the kitchen, cooked a fresh meal, and fed Narendra.

When she returned to her mat in the drawing room, Gajadhar babu told her, ‘Such a big girl! And she cannot cook an ordinary meal?’

‘Of course she can cook,’ the bitterness was back in the voice of Gajadhar babu’s wife. ‘Thing is, she does not want to do it.’

Next evening, seeing her mother busy in the kitchen, Basanti quickly changed into outside clothes and walked towards the front door.

Her father, lying there on his cot, stopped her.

‘Where are you going?’

‘There,’ Basanti did not even look at her father, ‘to Sheela’s house.’

‘No need to go outside,’ Gajadhar babu said sternly. ‘Go to your room and study.’

Basanti stood there silently for some time, stunned at being stopped by her father, unable to know what to do next. Seeing no way out, she returned inside the house.

When Gajadhar babu returned from his evening constitutional, his wife asked him, ‘What did you tell Basanti? She has been upset since noon. She hasn’t even eaten her lunch.’

Though his wife didn’t say it harshly, the bitterness her words implied got to Gajadhar babu. He felt as if his wife were accusing him of their daughter being upset. He decided to get Basanti married off as early as possible.

After that incident, Basanti started avoiding her father. If she had to go somewhere outside, she left through the door at the rear of their house. When Gajadhar babu asked his wife about Basanti’s behaviour, she simply said, ‘She is still upset.’

The report on his daughter’s behaviour made Gajadhar babu angry.

‘Such temper this girl has! She wouldn’t talk to her father just because he stopped her from wasting her time outside and told her to study at home instead?’ After the incident with Basanti, Gajadhar babu had another shock waiting for him. His wife informed him that Amar was thinking of leaving the house and setting up a separate household.

‘Why?’ Gajadhar babu was stunned.

He did not get clear answers from his wife. All he could gather from her was that Amar and his wife felt that Gajadhar babu stayed in the living room all day, so it became embarrassing when some visitors came as there was no place to seat

those visitors. Also, Gajadhar babu treated Amar like a child and gave him unwanted advice. Amar’s wife complained that she had to do the household work, while her mother-in-law kept on commenting on how wasteful she was.

‘Did they talk of leaving the house before I returned?’ Gajadhar babu asked his wife.

His wife shook her head in the negative. Before Gajadhar babu’s return, Amar was the master of the house. No one stopped Amar’s wife from doing the way she pleased. Amar’s friends often came home and hung around for a long time. Everyone was fed tea and snacks from the kitchen. Even Basanti enjoyed all those loud gatherings.

‘Tell Amar to think again,’ Gajadhar babu said to his wife. ‘There is no hurry.’

Next morning, when Gajadhar babu returned from his walk, he saw that his cot was not there in the drawing room. He did not know who to ask, there was no one around. Then he spotted his wife in the kitchen. He wanted to ask her why she, and not Amar’s wife, was in the kitchen; but he thought something and decided to remain quiet. He peeped into his wife’s room and saw that his small cot had been placed in the midst of pickles, quilts, and canisters. Gajadhar babu took off his coat and looked around for something to hang it from. He folded his coat, moved some clothes on the clothes horse, and placed his coat at one end of the clothes horse. He did not eat breakfast. He just lay on his cot. He was growing older. He managed to go for constitutionals every morning and evening, but he got tired easily.

Gajadhar babu remembered his wide, open railway quarter. There was a certainty to his life as long as he had his job. The way the station came to life on the arrival of the morning passenger train. Familiar faces of co-workers and regular passengers. And the thud thud thud thud rumble of the train’s wheels on the railway tracks. That rumble was like music to Gajadhar babu’s ears. The roaring of the engines of the high-speed Toofan Mail and express trains were the companions of his lonely nights. Some workers from Seth Ramjimal’s sugar mill nearby would come to the station and hang out with him. They were his friends. That was Gajadhar babu’s circle. The life he had left behind seemed like a lost treasure to Gajadhar babu. He felt cheated by life. He had not been allowed to have even a drop of all that he had

expected from life.

Lying on his cot in his wife’s tiny and dank room, he listened to the various noises in the house. The mother-in-law and the daughter-in-law were having a small altercation. There was a bucket filling at the tap. There was the clanging of utensils in the kitchen. And, in the midst of all those harsh noise, two sparrows were tweeting with one another.

He made up his mind. He wouldn’t interfere in anything happening in his family, his own house. If the master of this house, the man who built this house with his hard-earned money and whatever limited means he had, deserved to have only a small cot tucked inside a small space, then so be it. He would stay there in that small space. He wouldn’t protest or demand anything more. If his cot was moved again and placed somewhere else, he would again shift; but, again, he wouldn’t protest.

If his own children did not have a place for their father in their lives then he would better live like a passing traveler.

After that day, Gajadhar babu did not say anything to anyone. When Narendra came to ask him for money, he quietly gave him money. Basanti spent all her time in the houses of their neighbours, but he said nothing to her. Nothing affected or hurt him anymore.

Only one thing affected Gajadhar babu. Gajadhar babu’s biggest regret was that his own wife had not been able to notice the changes that had come in him. She seemed oblivious to the burden he was carrying around in his mind. She did not even wonder at the way her husband had stopped interfering in the goings-on in their house. On the other hand, much to Gajadhar babu’s disappointment, his wife told him, ‘It’s right. You don’t say anything to the children. They have grown up. We are doing our duty. We are educating them. When time comes, we would get them married. Our job would be done.’

Hurt, Gajadhar babu could only stare at his wife. He was assured that he had always been just a money-making machine for his wife and children. He was a man whose presence entitled his wife to line a parting in her hair with sindoor, the symbol of a married woman. He was a man whose presence gave his wife a distinction in the society as a married woman. But his wife was certainly not realising that. She just placed food before him two times a day and thought her duties towards that man to be over. She was so busy with her boxes of ghee and sugar that those boxes had become her world. Gajadhar babu could never be the centre of his wife’s life. He would have to live on her periphery.

His decision to not interfere in the daily happenings in his house did not affect anyone. In fact, his very presence in that house had started seeming as incongruous as his cot had seemed in the living room. The happiness he had felt at returning home after retirement had already turned into a deep sorrow.

Despite his efforts to stay indifferent, one day, Gajadhar babu ended up interfering in something. His wife was complaining like always that their domestic help was a useless man. He filched the money that he was given to buy things from the market. When he sat down to eat, he just went on eating, taking one helping after other.

Gajadhar babu had realised it pretty early on that maintaining a domestic help was an extravagance his family was not equipped to afford. When he heard his wife complaining about the domestic help again and again, he had it. He paid the man whatever was due to him and dismissed him.

Amar returned from office and called the help. Quite obviously, no one came. His wife gave him the shocking news.

‘Babu ji has sent the servant off.’

‘Why?’ Amar was stunned.

‘He thinks it is too expensive to keep a servant.’

It was a plain conversation between a man and his wife about domestic affairs. But the way Amar’s wife heaped accusations over her father-in-law hurt Gajadhar babu. Deeply upset, he did not go for his walk. His mind and body weary, he did not even switch on the light in his wife’s room. His family did not know he was still inside the house. The darkness had made him invisible to his wife and children.

‘Amma,’ Narendra told his mother, ‘why don’t you tell Babu ji anything? The kind of ideas that he is having, lying idle all day! He chased our servant away. If he thinks that I will take the wheat to the flour mill on my bicycle, I am not doing it.’

‘Yes, Amma,’ that was Basanti. ‘I have to go to college and then I have to sweep and mop the house. I can’t do all that.’

‘He’s an old man,’ Amar sounded annoyed. ‘Why can’t he just keep lying down all day? Why does he have to interfere in all that we do?’

Apparently hurt by what Amar said about his father, Gajadhar babu’s wife told him, ‘Yes, when your father couldn’t think of anything else, he sent your wife to the kitchen to cook our meals. She went and finished our provisions for fifteen days in just five days!’

Before Amar’s wife could react, Gajadhar babu’s wife went inside the kitchen. Sometime later, she came to her room and switched on the light. She melted in embarrassment upon seeing her husband lying there quietly. But she couldn’t tell if her husband were awake or asleep. His face was calm, his breathing steady.

One day, Gajadhar babu brought a letter to his wife. She was working in the kitchen. She wiped her wet hands in her sari and took the letter.

Before she could respond, Gajadhar babu said plainly, ‘I have found a job in Seth Ramjimal’s sugar mill. Instead of lying idle the entire day, it is better to

work and earn some money. He had proposed this job earlier, but I had refused then.

This time, I agreed.’

Gajadhar babu’s wife couldn’t say anything. Instead, Gajadhar babu spoke again, like an ember still struggling to stay aglow in a dying fire, ‘I had thought that after working and living away from all of you for thirty-five years, I would live in my own house, with all of you. Anyway, I have to leave day after tomorrow. Will you come with me?’

Gajadhar babu’s wife was shaken out of her stupor. ‘Me? But what will happen of the house? And what will happen of Basanti? She is still young and unmarried.’

‘No issue at all,’ Gajadhar babu said. ‘You stay here. I just asked.’ Then he went quiet.

Narendra tied his father’s bedroll eagerly and called a cycle rickshaw. He placed Gajadhar babu’s tin trunk and bedroll on the rickshaw. Holding a basket containing ladoos and mathri, Gajadhar babu climbed on the rickshaw. He saw his house one last time, and then he turned his eyes towards the road ahead. The rickshaw moved forward.

After Gajadhar babu’s departure, everyone came inside the house. Amar’s wife asked him, ‘When are you taking me to the cinema?’

Basanti jumped up. ‘Bhaiya, I’ll also go.’ Gajadhar babu’s wife went straight into the kitchen. She packed all the remaining mathris in a box and brought them to her room where she placed that box near her canisters. After that, she came out of her room and called Narendra.

‘Arrey, Narendra! Are you listening? Take your father’s cot out of my room and keep it somewhere else. There is no space in my room to even move freely.’

*********

Usha Priyamvada, 91, is emerita professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, the US, and author of several short stories and novels such as the well-known Pachpan Khamben Lal Deewarein.

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, 39, is a novelist, who works and lives in Chandil, Jharkhand.