Updated: August 15, 2022 12:54:06 am

SD Sharma (sitting) with Dr SS Bhatti at Le Corbusier Centre in Sector 19, Chandigarh. Archive

SD Sharma (sitting) with Dr SS Bhatti at Le Corbusier Centre in Sector 19, Chandigarh. ArchiveAs India commemorates its 75th year of Independence, the past, present and future come alive in the memories of those who witnessed the pain of the Partition and the spirit of a free country. These women and men recount the defining moments of a new chapter in their lives, a long and eventful journey that began with freedom. Against all odds, their hope is to build bridges between nations, as they relive the acts of kindness and generosity beyond borders.

‘It’s never easy to leave one’s wattan’

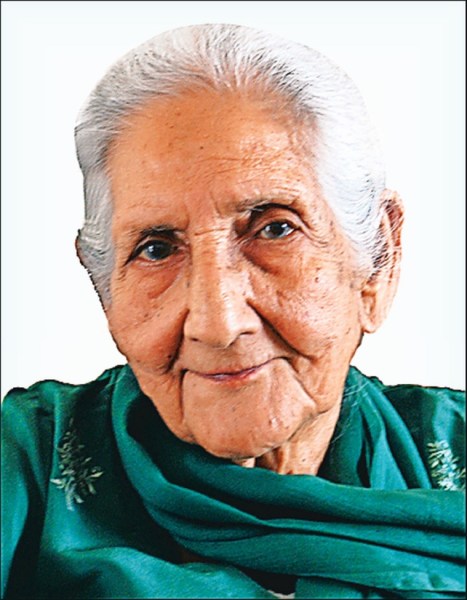

Susheel Gill, 97

Susheel Gill, 97

Susheel Gill, 97 We left our home in Sargodha (now in Pakistan) at a moment’s notice. There was no time to pack any personal belongings or bid farewell to friends. We just locked our houses and hastily departed, nurturing the hope that we would return after things settled down. I feel we were among the lucky families who crossed the border just before the massacre started. My father had a second factory and home in Khanna (Punjab), so we had a safe roof over our heads.

Subscriber Only Stories

It’s never easy to leave one’s wattan, one’s homeland. You are forced to abandon your friends and community – the sight, sound, smell and feel of everything that was familiar and beloved. East Punjab felt alien.

I was 22 years old and pregnant with my second child. My husband was a Captain in the Army and responsible for organising convoys to provide safe passage to refugees on both sides of the border. We were posted in Ambala and had been allotted a bungalow with a large compound in the cantonment area. When the violence increased, the household staff (almost all of whom were Muslim) fled to Pakistan. I was a young woman left alone in a large, empty house. To try and provide me with some protection, my husband left behind a gun and taught me how to load and fire it. Fortunately, I never had to use it.

Every few days, I would receive a message to let me know that members of my husband’s extended family or community were going to cross the border and come live with us. Because of the chaos and uncertainty, there were no specific dates for arrival. Every night, I would go to the railway station and wait for the trains coming from Pakistan. The station master would urge me to go home: “Bibi, all that is coming across are dead bodies.” But I couldn’t leave just in case someone had survived the journey, someone who had perhaps been hidden from view by the dead bodies. The trains would pull in and all that I saw were compartments piled with dead bodies dripping blood.

Our house soon became a sarai, with people spilling out into the verandahs and garden. As the ‘bahu’, I was expected to take care of everyone: to cook, clean, wash clothes and provide bathwater drawn from the handpump. The wailing of the new arrivals would continue for hours. I worried about the effect this would have on my daughter, who was just four years old, bewildered by what was happening.

Who could have thought that India would be partitioned? People talked about it hypothetically, but we believed – perhaps because we were desperate in our hope – that wise leaders on both sides would prevail and work out a compromise solution.

There was cruelty and savagery on both sides. And yet, there were also innumerable acts of kindness, compassion, generosity and tremendous courage on both sides. Despite the risk of being discovered and killed as traitors, Muslim families had provided shelter to Hindus and Sikhs, even as Sikhs and Hindus had sheltered Muslims.

My mother had provided a safe haven to several Muslim girls and women in Khanna while they waited to be safely evacuated. On several occasions, she had to use her negotiation skills to turn away gangs that came demanding that the Muslims be handed over to them. My father, who had stayed behind in Sargodha after we left, was protected and helped by his Muslim friends to safely reach the Indian border. A few weeks after the violence had finally died down, he received a message from his factory manager, a Muslim, asking him to meet at the border. When he reached there, he was handed a cloth bundle containing all the cash and jewellery that he had left behind in his safe.

During discussions on the horrors of Partition, it is these acts of compassion and personal courage that my husband and I also chose to remember. We would remind our children that both good and bad existed in every community and that it is our responsibility to build bridges of understanding and mutual support. We need to remember the horrors of the Partition and realise that all we can ever gain from fanning the flames of religious zealotry and bigotry, is ashes and rubble.

(Susheel Gill is a resident of Sector 35, Chandigarh)

‘We hope together we can build a great nation’

SD Sharma, 91

We need intellectual rigour, and creative potential to reinterpret the great Indian tradition of art, architecture, culture, and spirituality. What we need at this hour to make India great is holistic humanism.

(SS Bhatti is a former principal of the Chandigarh College of Architecture, and resides in Sector 15, Chandigarh)

‘People stood together, never losing hope’

Raman Mann, 79

Raman Mann, 79

Raman Mann, 79 On reaching Khanna everything seemed different. The atmosphere was gloomy and nobody seemed to laugh. There was fear in the eyes of most people, especially amongst the Muslim staff. Their friends around would often pacify them by patting them compassionately on their backs as if to say, “Don’t worry we’re safe here – we’re all together!”

- The Indian Express website has been rated GREEN for its credibility and trustworthiness by Newsguard, a global service that rates news sources for their journalistic standards.