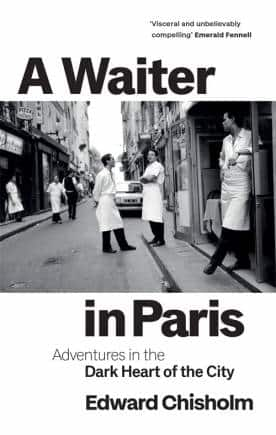

'A Waiter in Paris' is also a portrait of another Paris, one that is found in the seedier stations of the Metro. (Representational image: Tony Lee via Unsplash)

Ah, Paris. Catching sight of the glowing Eiffel Tower during a night-time cruise on the Seine. Discovering a charming boulangerie while strolling down the streets of the Marais. Gazing at the view from the steps of the Basilica of Sacre Coeur after exploring the lanes of Montmartre. Striking an existentialist pose while sipping cocktails at the Les Deux Magots.

The starry-eyed visitor can often miss the shadows in this City of Light. It’s also home to deprived families in banlieues, desperate yellow-jacketed workers, immigrants with and without papers, and others facing low standards of life because of the high cost of living. Not exactly an episode of Emily in Paris.

A reminder of this from 1933 is in George Orwell’s first published full-length work, Down and Out in Paris and London. Here, he recollects the destitute weeks he spent working in the kitchen of the upmarket Hôtel Lotti on the Rue de Rivoli.

A reminder of this from 1933 is in George Orwell’s first published full-length work, Down and Out in Paris and London. Here, he recollects the destitute weeks he spent working in the kitchen of the upmarket Hôtel Lotti on the Rue de Rivoli.

Orwell was employed as a plongeur, a person who washed dishes and carried out other menial tasks from morning to night. “There sat the customers in all their splendour - spotless table-cloths, bowls of flowers, mirrors and gilt cornices and painted cherubim,” he recalls, “and here, just a few feet away, we in our disgusting filth.”

All these years later, fellow British writer Edward Chisholm takes a cue from Orwell to write about his experiences in a new book, A Waiter in Paris. Unlike Orwell, who was largely confined to the kitchen, Chisholm was - as marketing consultants would say – in a customer-facing role.

After holding down a string of petty jobs in London, Chisholm moved to Paris to be with his girlfriend. The relationship came to an end, but he decided to stay on despite a limited knowledge of French and an even more limited supply of funds. It was, he discovered, “far from the glimmering parties of F. Scott Fitzgerald, or the literary salons hosted by Gertrude Stein, with Hemingway, Picasso and Matisse.”

Chisholm went on to spend several years in the French capital, working in restaurants and bars while trying to build a career as a writer. A Waiter in Paris is based on his stint in one such restaurant, though it contains an amalgam of all his experiences in the city. These include an incipient romance, attending a wedding, and drunken revelry.

The book immerses you in the goings-on behind the scenes of a public dining room. This labyrinthine world lies beyond the “high ceilings and low lighting, flaking gold-rimmed Louis XV mirrors, wallpaper with fleur-de-lis motifs and large single-glazed windows.” It’s a private universe of kitchens, storerooms, cleaning rooms, corridors, and narrow staircases.Here, there are brutal fourteen-hour shifts, claustrophobic conditions, strained tempers, and cutthroat competition for tips. “The truth is,” Chisholm writes, “a Parisian restaurant is an inefficiency-riddled structure that’s manned by underpaid and underfed slaves.”

As in Orwell’s time, such an environment leads to questionable standards of hygiene. To check that the dishes are hot enough to be served, the staff “stick their fingers in sauces, prod pieces of meat, nibble vegetables.” Hands that have been “dealing with the dirty plates and shoving our gelled hair back into place” also rearrange duck breasts and push around haricot beans.

Chisholm is first employed as a runner, a person who assists waiters by fetching food and drink and clearing tables. Initially bewildered by rapid-fire instructions, he tries to learn the arts of collecting dishes and navigating the room with glass and plate-laden trays. After months of being humiliated, screamed at, and hustling for his fair share of tips, he becomes a waiter in his own right.

Part of the appeal of Orwell’s book lies in the description of the characters he encountered during his scullery duties. Chisholm’s book, too, contains a singular gallery of “thieves, narcissists, former Legionnaires, wannabe actors, paperless immigrants, drug dealers.”

At one point, Chisholm serves a couple and hears the woman exclaim: “Our first proper French breakfast in Paris, honey.” Yes, he thinks, “this Parisian breakfast, from me, the English waiter who took the order, to the Tamil Tiger who made the coffee and pressed the orange juice and the West African expelled from the UK who heated the factory-made croissants.”

Two threads run through the details that season these pages. The first is of waiting, in both senses of the word. While Chisholm and his colleagues at the restaurant wait on tables, they also wait for a better future. For some, the task is Sisyphean and the wait is never-ending.

The other theme is the tension between the façade and the interior. If a waiter is doing his job correctly, Chisholm learns, he will be manipulating the diner’s perception of reality. The skilled waiter is an illusionist and “his job is to deceive you.” He wants you to believe “that all is calm and luxurious, because on the other side of the wall, beyond that door, is hell.” This then, is the source of the legendarily snooty Paris waiter’s behaviour: taking pride in playing a Sartrean role that goes back a long way.

Somehow, Chisholm manages to survive dismal working conditions, nights in bedbug-infested lodgings, and all-consuming anxieties about not being able to pay his rent or afford a meal. At times during a respite from his duties, he takes to visiting a nearby five-star hotel to nap in the toilets.He is aware of his relative privilege. “The poverty and humiliation I felt in these jobs will never come close to those of the people I encountered,” he realises, “for they are not living a job, but a life.” Why, then, does he stay on?

His answer: when you’re in Paris you couldn’t care less about anywhere else. “No matter how much your feet hurt after a never-ending shift, how physically dead you feel as you walk up the Avenue de l’Opéra at night, or across the Seine under the shadow of Notre-Dame, inside, you can’t help but feel intensely alive…it’s the centre of the universe.”

The city, of course, was also the site of the Paris Commune and the storming of the Bastille, among other revolutionary events. Chisholm must have imbibed something of this spirit because at times his thoughts turn towards class struggle.

“When we are hungry, or our feet ache, or we are denied a break, or have to work three weeks without a day off,” he writes, “it is because the management consider us acceptable casualties when it comes to carrying out their duty and hopefully getting promoted.” He dreams of a revolution in which waiters of the world unite against grasping employers. In time, he hopes, diners will join in to demand not only fair treatment for staff, but greater transparency when it comes to what they are eating and drinking.

A Waiter in Paris, then, is not just about a stint at a restaurant. It is also a portrait of another Paris, one that is multilingual and multi-ethnic, found in the seedier stations of the Metro and the rubbish-strewn streets of dingy flats, pharmacies, massage parlours, tobacco shops, and estate agents.The book gives voice to a hidden workforce, bringing to light stories that, as Chisholm says, are also being played out in London, Paris, New York, Berlin, Madrid, and Rome. He could well have added Indian metropolises to the list.